The 8 disciplines of innovation and how to excel in each of them

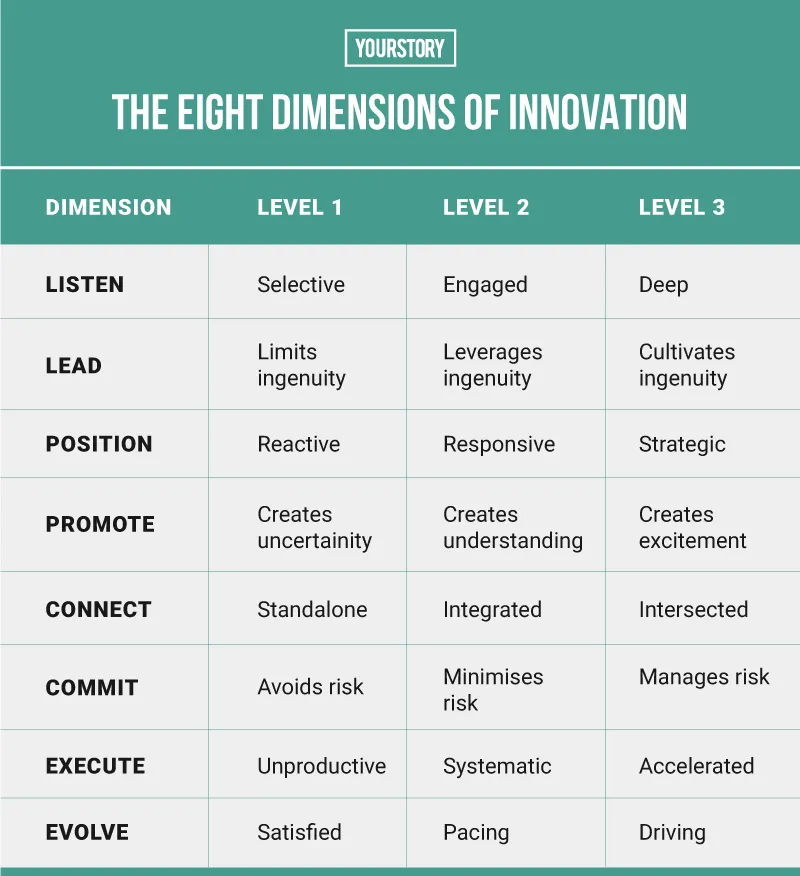

This useful book provides frameworks and maturity levels for eight innovation paths: listen, lead, position, promote, connect, commit, execute, and evolve.

Effective frameworks and examples of corporate innovation are provided in Madge Meyer’s book, The Innovator's Path: How Individuals, Teams, and Organizations Can Make Innovation Business-as-Usual. The material is spread across 232 pages, and makes for an informative read.

Madge Meyer was formerly the Executive Vice President and Chief Innovation Officer at State Street Corporation. Her teams have won over 30 innovation and excellence awards under her leadership. She was earlier at Merrill Lynch and IBM, and serves on a number of organisational boards.

The insights in this book will be useful for CEOs, CIOs, CTOs, entrepreneurs, and academics alike. See also my reviews of the related books, Quirky, Frugal Innovation, Multipliers, Trillion Dollar Coach, Igniting Innovation, The Innovation Formula, and The Innovation Engine.

Here are my key takeaways from the book, also summarised in Table 1 below. Each of the eight disciplines is classified into three levels of maturity, from early-stage to excellence. The author digs beyond the ‘usual suspects’ and showcases innovation in IT services, medicine, manufacturing, finance, academic-industry collaboration, and even the restaurant business.

The innovative organisation

Madge defines innovation as “any idea or solution that creates business value and increases competitive advantage”. It can be a product, service, process or strategy.

The eight paths are not meant to be followed in a strictly linear manner, the author explains; there is much back and forth in the innovation journey. Some innovations are world-changing, some are substantial and strategic, and others have smaller impact but still create significant value.

Successful innovators are open to alternatives as long as they have the potential to reach the goal, and are willing to shed old assumptions. They do not rest on their laurels and keep moving to the next innovations. “Change is hard, but constant change is harder,” Madge emphasises.

In a truly innovative organisation, innovation is business-as-usual. It can arise on any day and from any employee, and not just the R&D or strategy department. Advances and convergences in cloud computing, mobiles, online collaboration, and social media are accelerating and magnifying innovation as never before.

1. Listen

“Hearing and listening are as different as noise and music,” Madge emphasises. Listening is much deeper than hearing, and calls for patience, humility and respect. Listeners suspend their own disbelief and judgment, and enter the speaker’s reality.

Listeners must acknowledge the limits of their own knowledge, and pay close attention to what is being said, and what is not being said. It is important to listen for the hidden wealth of insights across organisations, partner networks, industries, and generations.

Leaders must listen to facts as well as to their people; they must be open to ‘disconfirming data’ as well. They must encourage people to communicate honestly and openly, and listen to their concerns and suggestions.

Listening occurs at three levels. In selective listening, we only seek confirmation for what we want to hear, and ask narrowly-focussed questions. In engaged listening, there is dialogue and expansion of understanding. In deep listening, we uncover speaker assumptions and motivations, read body language, probe deeper, and listen to what is not being said.

At the same time, innovation leaders must hold on to their sense of intuition. Customers may not always know what is possible or what new technologies are around the corner (‘fast horses vs. cars’).

Bringing together diverse inputs and mindsets helps brainstorming and sensemaking. Examples include IBM’s collective online jam for ideas and values, client service quality assessment at State Street, and innovation capability sensing at NetApp.

2. Lead

Leadership is about inspiring others to achieve beyond their expectations. Respect, trust, and integrity are key attributes of leadership. While some leaders are serious, reserved and impersonal, others indulge in humour, storytelling, and sharing of personal anecdotes.

Leaders have a vision for the future and ignite the passion of others towards that goal. They unite teams through a sense of shared purpose and shared adventure. They communicate with clarity and urgency, and have strong emotional intelligence and empathy. They are also willing to learn from their mistakes and change themselves.

“High performers can accomplish many things, but great leaders accomplish even more because they inspire and align others,” Madge observes. “People are more creative, productive, and bonded, more willing to help each other and collaborate, when they are having fun,” she adds.

“Great leaders have a sense of tomorrow,” she explains. They have sound judgment and instinct, and are able to anticipate issues. But being an innovation leader calls for much more – they must create a culture of innovation.

“Culture is an organisation’s collective assumptions, norms and values. It defines what is – and what is not – acceptable behaviour, using both positive and negative reinforcement,” Madge defines. “The most important key for unlocking the ingenuity of our people is the one that changes how we think about and manage failure,” she emphasises.

Failure can be painful for the innovator, but is an important part of the path to success. Failures may be perceived as jeopardising to reputation, careers and jobs. But companies should frame failures as lessons that are incorporated into future operations, and not penalise or shame individuals.

“To move forward, leaders must introduce and maintain a failure-tolerant culture,” Madge explains. Rapid experimentation, fast failure and quick learning are key. The lessons must be shared widely so that the failure is not repeated.

At the same time, fallout should be mapped and managed; companies must be careful about failures that may cause risk to customers and damage to brand. Guidelines for calculated risks should specify the tolerable limits of downsides.

Many companies unfortunately have leaders with a ‘compliance’ mentality, and do not want to change the status quo (‘limit ingenuity’). The next phase is ‘leverage ingenuity,’ where enthusiasm is encouraged but with short-term limits. The third phase is ‘cultivates ingenuity,’ where long-term vision is articulated along with an opportunity for everyone to rise up and contribute to innovation.

3. Position

Positioning innovation involves defining an agile, strategic roadmap toward the future. It includes scenarios, milestones, and timetables. Crises like natural disasters, disease outbreaks, and political unrest also open up opportunities for companies to position themselves as leaders in business continuity planning, Madge advises. (This book was written before the coronavirus outbreak, and this observation is even more applicable now.)

In terms of the evolution of maturity in positioning, Madge describes three levels: reactive (limited vision; firefighting), responsive (with vision; quick responses), and strategic (anticipating trends, preparing in advance). “Position for tomorrow, not today,” the author urges.

Examples include Symantec repositioning itself as a security leader from the PC to the Internet world, and selling off unrelated companies in areas like contact management. It rode the Nimda virus attack wave and acquired Veritas to lead the market for backup and recovery.

State Street repositioned itself from a traditional bank to a custody bank in mutual funds and pension. Its IT innovation teams shaped its global data centre and cloud strategy, along with global virtual teams.

4. Promote

Promoting innovation is about conveying its value. While some innovations may be secret ‘skunk-works’ and operate in isolation, many others call for evangelising, getting buy-in, enlisting support, seeking funding, and roping in resources.

This has implications for personal, team, and organisational brands, Madge explains. The value proposition or innovation impact from a baseline must be clearly articulated. Payback periods and metrics should be spelt out, along with assumptions and risks.

Innovation projects should be managed differently from traditional projects, Madge cautions. A range of internal and external communication channels and platforms should be leveraged.

Winning innovation awards serves as a huge motivator as well, beyond fact-based promotion. Credit should be given where due; a “thank-you culture” helps in this regard while promoting innovation success stories.

Madge describes three levels of promotion maturity in this regard: creating uncertainty (no clear articulation of value), creating understanding (clear communication of value, building knowledge), and creating excitement (buzz, enthusiasm, industry benchmarks).

Examples include State Street’s innovations in environmental sustainability and green programmes. They showed impacts in reduced consumption of electricity and water, and received 12 industry awards. Progress was communicated through internal townhalls and external social media.

5. Connect

Innovative organisations connect at multiple levels: interpersonal relationships within the organisation, as well as linkages across organisations and industries. Many innovations are ‘collective accomplishments,’ and organisations benefit from inputs across professions, generations and countries.

Innovations require not just more water but more nutrients, according to Tenley Albright, director of MIT Collaborative Industries initiative. The consortium brings together entrepreneurs and professionals from a range of industries for the infusion of new ideas to solve complex problems.

“Creativity is just connecting things,” in the words of Steve Jobs. For innovation initiatives, even a company’s vendors can become strategic partners, Madge explains. Going to outside sources improves external sensemaking.

Innovation involves not just competition but also coopetition across the industry. Attending industry events opens up new insights and connections; inviting external speakers to one’s organisation widens horizons as well.

Standalone innovation carries risks of the silo-type mentality, and relationships are limited only to transactions. Integrated connections span diverse stakeholders, and intersected connections go beyond the usual industries, technologies and age groups, Madge describes.

Examples include Costco’s research in Central American villages for understanding sustainable farming; surgical robots borrowing practices from the automobile sector; and MIT’s Albright Challenge to tackle complex problems.

Madge explains that in Chinese culture, people make connections with others even if they don’t need anything from them right now; the value may emerge only later. Connections span work-life and personal-professional boundaries as well.

Within organisations, an open, friendly and inspirational environment spurs connections for innovative ideas. In global teams, constraints of geography should be tackled to remove ‘logjams’. Madge shows that even choosing the seating arrangement during team dinners help spur formal and informal connections.

“Connect generously – do not be calculating constantly,” Madge advises. “Help to connect other people together for their mutual benefit,” she adds.

6. Commit

Commitment is where the ‘rubber meets the road,’ and involves creating a culture of safety for innovation along with allocations of funds, time and leadership resources. Commitment is about motivating and aligning ingenuity in the organisation, Madge explains.

This also involves allowing people to mistakes and ‘failing constructively.’ Lessons should be captured and applied in future activities. Failure should not be ridiculed or shamed; innovators should be supported and encouraged, the author advises.

Safety zones should be expanded, and fear should be driven out. Though companies want to maximise conformity and predictability, they should calculate risks in innovation and develop a portfolio of new projects.

“The commitment is to maximise organisational learning and growth rather than meet present project delivery expectations,” Madge explains. Innovation initiatives call for new governance models and evaluation criteria.

Early failures allow for assumptions to be tested quickly. It can be a tough call to decide when to switch course and abandon existing initiatives, given how market timing can be tricky and unpredictable.

“People need to be comfortable openly discussing what failed and why, so they and others can learn,” Madge emphasises.

Examples of commitment to organisational innovation include IBM’s Emerging Business Opportunities programme. It identifies, funds and shepherds new ideas, and led to successes in open source and life sciences businesses.

In terms of commitment to innovation, Madge divides companies into three types – those who avoid, minimise and manage risk. In the final stage, risks are carefully calculated, and fast experimentation is encouraged; commitment is made, but is flexible.

7. Execute

Innovation is not just about envisioning but also the achievement of high impact, quality, and standards. “Acceptable failure is a matter of raising our sights, not lowering our standards,” Madge clarifies.

Innovation execution involves scope management, timeliness and rapid value delivery in phases. It is about impact and not just completion, as captured in the expression ‘The operation was a success but the patient died.’

Lack of focus or an inaccurate scope leads to unproductive execution. Systematic execution has a standard methodology, whereas accelerated execution brings in rapid experimentation and metrics to “track, communicate and celebrate progress,” Madge explains. Examples include State Street’s Innovation Lab to test and evaluate new technologies.

8. Evolve

Successful companies relentlessly accelerate the pace of innovation and challenge complacency and defensiveness. They recognise that even bonding among successful teams can produce a new and rigid status quo. They rotate people across the organisation, and learn from strategic future plans of all their stakeholders.

They always see room for new insights, opportunities, and improvement. They do not hold on to previous successes or rest on their laurels for long, as seen in the continuous wave of innovations from companies like Amazon.

Successful innovators race not just against others but against themselves as well. Clinging onto the past prevents you from seeing what is on the other side, Madge cautions. Continuous innovation creates business value and competitive advantage.

Companies should standardise on the culture and values of innovation, but other frameworks should not be rigid or stifling. Innovation culture should open up space for increasingly more contributors.

As industries evolve and customer habits change, companies must also learn when to shed outdated ideas and baggage of the past. New adversities will force successive waves of transformation at the individual and organisational level.

Madge classifies level of evolution into three types: satisfied (comfortable, complacent), pacing (alert and open to change), and driving (embedding innovation across processes). Entirely new solutions are ultimately sought, not just improvements to current solutions.

Examples include IBM’s ‘Think’ philosophy and fellowship programmes, Dean Kamen’s FIRST events for young innovators, and State Street’s internal online communities for innovations in sustainability and flexible work. Blue Ginger restaurant introduces seasonal changes in the menu, seating, and group service options.

In sum, the book provides a useful set of collective principles for organisational innovation. The eight critical skills help sharpen the problem spotting and solving skills of businesses. The book goes beyond the maverick and genius approach to show that creativity exists in us all, and innovation can be achieved in some measure by all employees in an organisation.

The book is packed with useful and inspiring quotes, and it would be fitting to end this review with the sample below.

Companies innovate by fostering a culture that strives to identify, embrace and reward change. – Marc Andreessen

A lot of innovation happens because of the ability to connect different technologies together and the new capabilities they enable. – John Swainson

Sensemaking is a quintessential part of leadership. But it’s also a quintessential part of large-scale innovation. – Deborah Ancona

If you love what you do, things just come so much more easily to you. – Ming Tsai

Successes and failures are a necessary part of innovation. – Linda Sanford

Failure is a kind of tuition. It’s a very expensive tuition. – Nathan Myhrvold

The broader one’s understanding of the human experience, the better design we will have. – Steve Jobs

There is always a way! We will find the way! If there is no way, we will build the way! – Hannibal

If you stay the same, you are getting worse. – Tom Mendoza

Edited by Saheli Sen Gupta