This Chennai startup helps farmers boost their income with a micro farm model

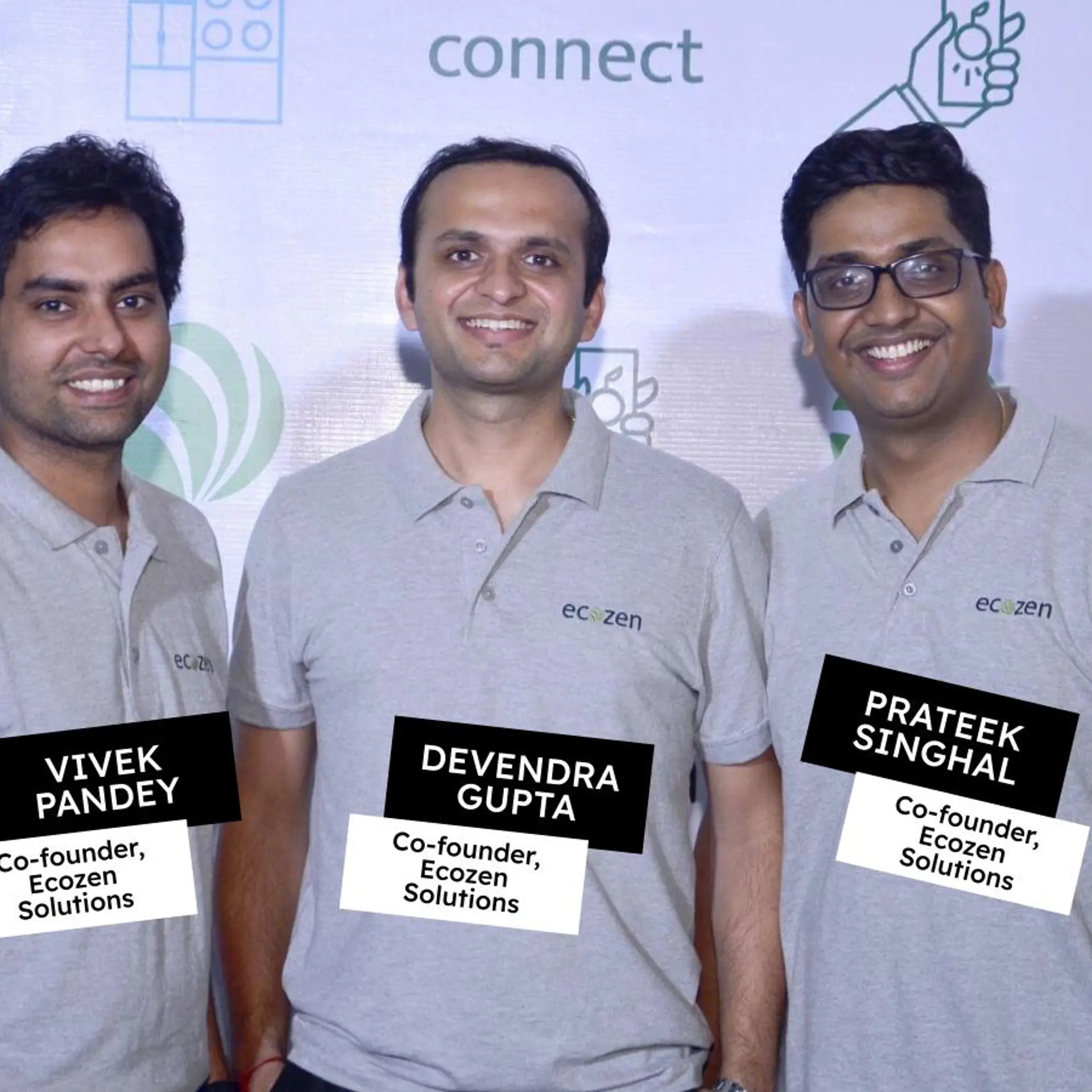

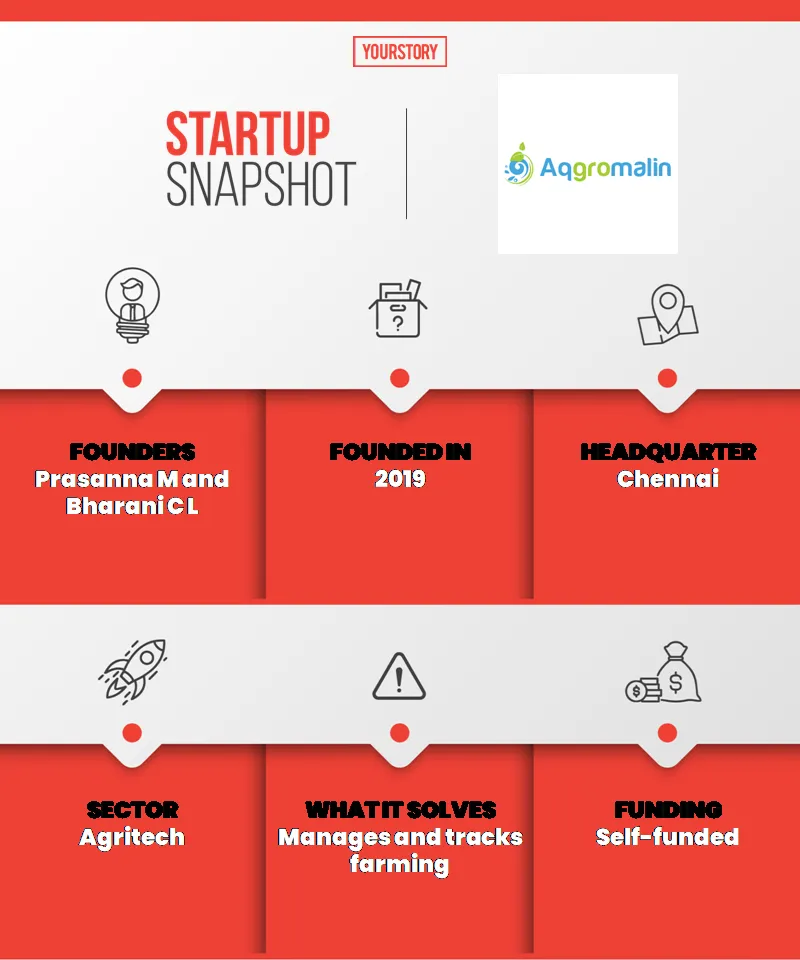

Agritech startup Aqgromalin, founded by Prasanna M and Bharani CL, helps farmers supplement their income by diversifying into animal husbandry and aquaculture.

A Chennai-based agritech startup founded in 2019 by two tech graduates aims to help small farmers mitigate risks from mono crop culture and earn additional income by diversifying into animal husbandry and aquaculture.

With Aqgromalin, founders Prasanna M and Bharani CL enable small farmers to access the input materials, technical instruments, training, and support needed to take up animal husbandry and aquaculture without too many additional requirements.

“We first conceptualised a farm-to-fork model in which we bring farmers closer to consumers and businesses,” says Prasanna. “But as we started working with a number of farmers, we felt there we more significant opportunities, where we could effectively contribute to creating a better impact on increasing their income.”

The founders say that in Tamil Nadu, most farmers were involved in paddy cultivation, which was not too profitable compared to the time and effort invested in yielding a good harvest.

“We then surveyed the progressive farmers in that area and found that a majority of them were involved in allied activities of animal husbandry and aquaculture,” says Bharani. “They were able to mitigate the risks arising from mono crop culture and were also able to see handsome returns.”

Snapshot

According to the Ministry of Agriculture, more than 100 million farmers out of 140 million farm households each own less than an acre. Many others own under two acres each. These are the small farmers Aqgromalin especially seeks to help in diversifying their income.

At present, the farm diversification integrator covers close to 10,000 acres and works with 600 farmers.

Easy farm set-up

Aqgromalin allows farmers to take up animal husbandry and aquaculture through its “ready to implement micro farms” model, which requires little space and investment, and is not too labour intensive, say the founders.

While farmers receive a lot of recommendations from stakeholders such as the government, traders, companies, and startups, they want to test a model before venturing into new activities.

So early on in 2019, Prasanna and Bharani built their model and invited farmers to see its benefit. Once the farmers were convinced, the founders began to see traction.

The model works thus: Say, a farmer invests Rs 1 lakh to rear fish, ducks, goat, and pigs and intends to sell the produce at a profit. Aqgromalin buys the produce and takes it across the distribution chain. The farmer can also take it to the market if the price offered is higher. The startup also provides an app that has information to track the growth of the produce and helps the farmer monitor the farm’s maintenance.

“We monetise by supplying inputs on a subscription model after every crop cycle,” says Bharani. “We also have a buyback option, where we help farmers sell their produce through our platform.”

At present, the startup works with farmers in Tamil Nadu, Telangana, and Andhra Pradesh.

“As the investment and space requirement is low, we’ve had more farmers take this model up in addition to the existing activities,” says Prasanna.

The model has become especially useful for women farmers to contribute to their household income, say the founders.

Gauging the potential

Chennai natives Prasanna and Bharani have been friends for almost 17 years and completed their engineering from the Madras Institute of Technology in 2007.

After engineering, Bharani worked with TVS Motor and Renault-Nissan, while Prasanna started an edtech company called Axiom in 2008. At the time, he designed an online test platform for competitive exams and trained students on that portal. After Axiom was acquired by another firm, the pair decided to launch an agritech startup.

They noticed that 85 percent of agritech startups were working in horticulture, while established companies including Venkateshwara Hatcheries and Suguna were involved in the poultry industry. Shrimp cultivation too yielded value, given that products are exported and bring foreign exchange to the country.

Animal husbandry and aquaculture are part of the allied agricultural sector, with a potential to become large industries. This prompted Prasanna and Bharani to focus on the two segments.

“We believe there are several product lines, which have the potential to gain the same traction as horticulture, poultry, and shrimp cultivation,” says Prasanna.

Scaling the micro farm model

Aqgromalin was bootstrapped for the first eight months after its launch, even as it gained traction from its micro farm model. After this, the founders approached some angel investors, says Prasanna.

So far, the startup has raised Rs 2 crore from some angels in West Asia.

"Having external investors believe in your vision and become part of the journey is always exciting for an entrepreneur," says Prasanna. "Customers validate your model and investors validate your vision; getting both at all times is critical for a company at all stages."

Being a privately-held company, the founders do not want to disclose its revenue.

The startup aims to set up 500 “ready to implement micro farms” in Tamil Nadu, Telangana, and Andhra Pradesh and ensure that its 600 partner farmers at least double their household income.

“As our work is predominantly in the rural areas, we encounter interesting challenges on a regular basis,” Bharani says of the scope for innovation at Aqgromalin.

The startup competes with agritech firms Ninjacart, Crofarm, CropIn, Farmizen, DeHaat, and BigHaat, among others. Although the agritech sector is yet to have a unicorn, Aqgromalin’s founders see a lot of potential for growth and innovation.

Aqgromalin founders

“With a significant number of startups coming into this space, access to credit and technologies has become easier for farmers,” says Prasanna. “They need to leverage these available resources and take the maximum advantage. For startups also this is a very exciting space, with increased activity over the last two years. The opportunities are immense and there is scope for innovation. With internet penetration, we’re seeing more farmers become tech savvy and willing to adopt new technologies.”

Edited by Lena Saha