BBNow’s game plan to get Bigbasket up-to-speed in quick commerce

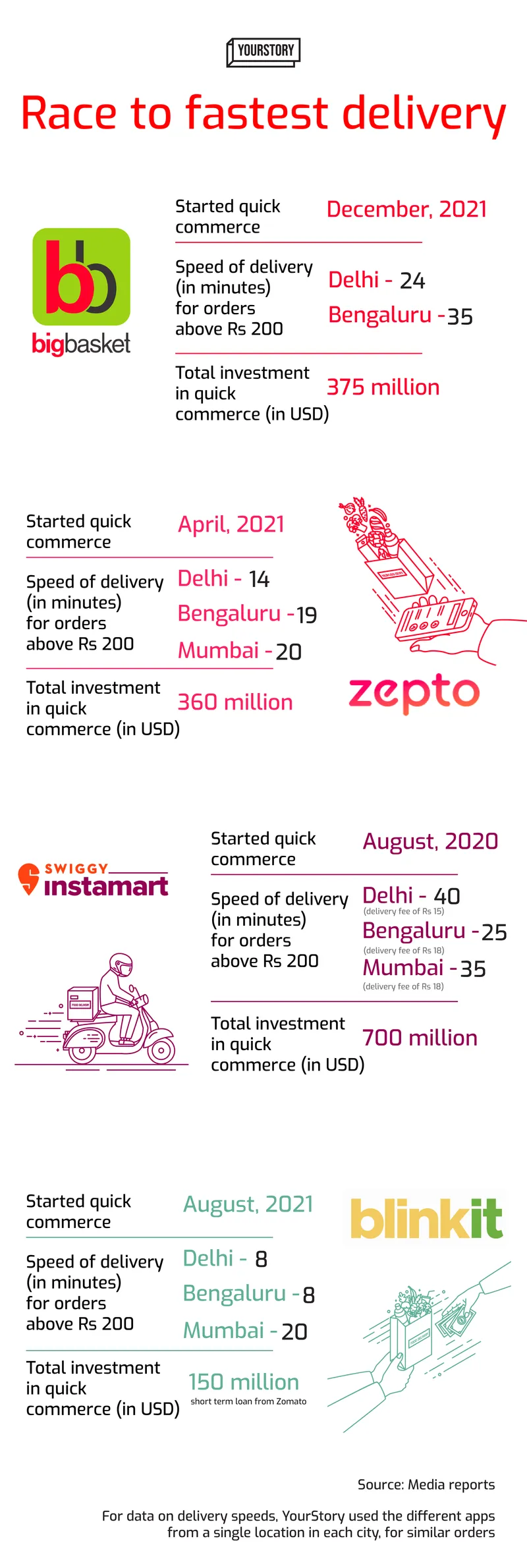

The quick commerce bet is too lucrative to ignore for Tata-backed Bigbasket, which entered the race as late as December 2021, taking on the likes of Swiggy Instamart, Blinkit, and Zepto.

In its early avatar in 2015-16, e-grocery player Express Delivery service set out to deliver essentials in 90 minutes for a fee. The model was later integrated into its scheduled grocery delivery business as the unit economics didn’t make sense, TK Balakumar, Chief Operating Officer at Bigbasket tells YourStory.

“Customer behaviour changes with time. We took the decision to enter quick commerce in September 2021, and we decided that we didn’t want to jump in unless our backend was ready,” Balakumar says.

And that’s how the earliest online grocery player—with a pedigree dating back to 2011—got into the fray with BBNow to compete with younger and well-funded players like and new businesses such as Instamart and -backed backed by established startups. Meanwhile, Ola Dash, the company’s second stab at quick commerce after 2015, wound down operations to focus on its electric vehicles business.

With an estimated market size of $5.5 billion by 2025, the resurgence of faster deliveries under the quick commerce model is too large to ignore. Backed by Tata Enterprises, Bigbasket cannot afford to cede ground to new players, especially in a vertical where it has built a strong supply chain and a loyal customer base.

“Swiggy, Bigbasket, Dunzo, etc, all specialise in different but critical legs of the quick commerce process. The key will be to perfect the entire consumer experience through quick learn-unlearn-relearn cycles. The need is there and the market scope is big enough for two to three of the top players to coexist,” says Bharat Birla, Director at Anand Rathi Advisors.

TK Balakumar, COO, Bigbasket

Officially launched in Bengaluru in December 2021 with two stores, BBNow now has a network of 160 stores across top 10 Tier I cities, covering nearly 50 percent of Bigbasket’s existing customer base. It plans to expand its dark store network to 300 stores across these cities by mid-August, to serve 80 percent of its existing customer base.

“There is a board approval to go up to 350 stores, including the next 20 cities or Tier II cities. We will add 40 stores in Tier II cities such as Lucknow, Kochi, Baroda, and Vizag. We have planned the capex for setting up these stores, which averages at Rs 50-60 lakh per store,” Balakumar says.

He adds that the company might seek interim approval to set up additional dark stores depending on the demand.

Earlier this year, Innovative Retail Concepts, the Tata-owned entity which is a subsidiary of Bigbasket, raised Rs 1,350 crore in two separate tranches from the parent entity, Supermarket Grocery Supplies.

What sells

With BBNow, the company started stocking up on top-up items, including fruits and vegetables, meat, and fish as well as groceries based on historical data available from the Bigbasket platform over the last six to seven years.

However, after data started emerging from the new dark stores, the team realised that the mix is very different from scheduled deliveries.

“In quantity terms, 40-45 percent of the order from BBNow stores constitutes fruits and vegetables as well as meat and fish. For scheduled deliveries, fruits and vegetables make up around 20 percent of the quantity,” Balakumar says.

He adds that meat and fish have been touching double digits in some regions for BBNow, from a national average of 3 to 4 percent of scheduled deliveries.

Another category that does well when it comes to quick commerce is ice cream, which is highly temperature-sensitive. However, customer behaviour changes across seasons as well as weekdays to weekends.

Differentiation from the competition

The BBNow network of stores is managed and operated by Bigbasket itself. The company asks the project team to scout for stores in a particular lat-long to serve the target area. The fitments of racks and cold storage are done by Bigbasket while the staff also works directly with the company.

“You have much better control over your processes, due to the nature of items you deal with–perishables, etc. I am not saying the franchisee model won’t work but we have chosen to run it ourselves as we will be able to drive it much better,” Balakumar says.

The average dark store is spread across 2,500 to 3,000 square feet, serving a radius of up to 2.5 kilometres.

While quick commerce has been pushing the envelope, BBNow aims to deliver the majority of orders in under 30 minutes, with 96 percent of them being delivered within 26 minutes.

“We started with 10 to 20-minute deliveries but that is overkill. It can take a delivery executive nearly 12 minutes to move from the gate to an apartment to the ninth floor of a high-rise. We do not want to pass on the additional pressure to delivery boys.”

Race to fastest delivery

What lies ahead

Quick commerce has brought in 20 percent new customers for BBNow at a city level.

Balakumar says this is also driven by the low cutoff or absence of delivery charges by quick commerce providers.

“It is still early days and we are sure every operator will get into imposing delivery charges. We will also look at it after early days and my thinking is quick commerce will turn into a premium service,” Balakumar says. He adds that SKUs are likely to see a premium pricing, with a difference of Rs 2 to Rs 3 per unit.

While BBNow is focused on getting its foot in the door in quick commerce, the company will evaluate any acquisition targets that might make strategic sense to the business. This could still be a way off, according to Bharat, of Anand Rathi Advisors, who adds, “Proof of concept has to be established before the sector sees consolidation.”

Edited by Teja Lele