More reservation, more rights, says TN trans community

Trans people in the state say horizontal reservation is the way forward to get more representation in government jobs.

U Swetha was born into a family of Devendrakula Vellalars—a community listed under the Scheduled Castes (SCs) of Tamil Nadu—in a village called Mayaleri in Virudhunagar district.

Swetha started feeling dissociated from her assigned gender at birth a few years before she hit her teens. But she contained the conflict brewing inside and outside of her with a stoic resolve to finish school and college.

After college, when Swetha's trans identity became apparent, her family stopped supporting her, and she resorted to begging and sex work.

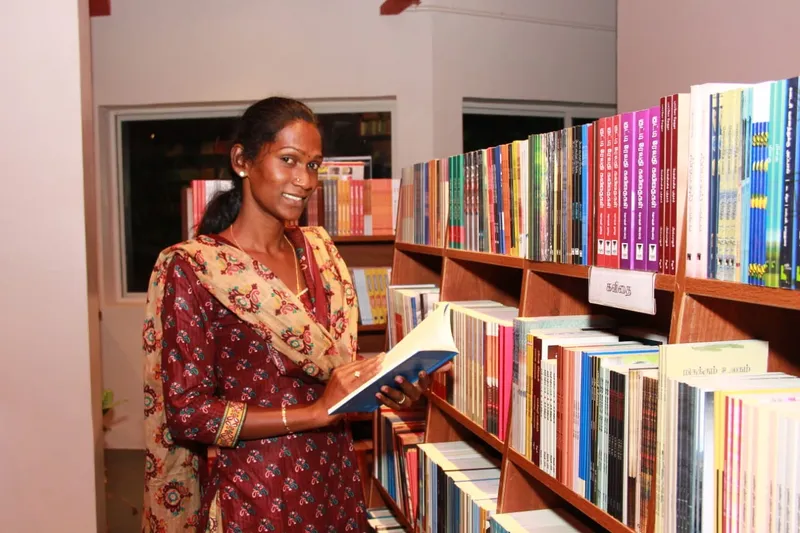

Transwoman candidate U Swetha didn't make the cut in the last TNPSC exam despite scoring more than 200 out of 300

In 2016, Swetha underwent gender reassignment surgery and recovered in seclusion before she landed a job as a pharmacist at an AIDS home in Chennai. In the meantime, she also prepared for the Tamil Nadu Public Service Commission (TNPSC) Group 4 exam for 2022.

"The exam saw 17 lakh candidates appearing for 7,000 posts. Of this, 152 candidates were trans, and at least 15 of them scored more than 200 out of 300,” says trans activist and artist Kalki Subramaniam.

“But, the fact that they competed with lakhs of Most Backward Castes (the quota allotted to trans people in Tamil Nadu) cis candidates in that exam meant the likelihood of them getting selected was negligible,” she says.

Why horizontal reservation?

On March 28, the TNPSC exam results were out, and no trans candidate had made the cut. Following this, in April, which marks Dalit History Month, Dalit-trans activist Grace Banu began a campaign demanding horizontal reservation for trans people in the state.

This, she believes, is the only way to address the intersectional discrimination the community’s youngsters face based on their gender, socio-economic status, and caste, as they enroll into public services.

Simply put, horizontal reservation happens when equal opportunity is provided to specific sections of the population, including destitute widows, women, veterans, the transgender community, and individuals with disabilities. It cuts through the vertical categories of caste and religion to ensure the most disadvantaged people within these groups get access to a level playing field. This right is argued under Article 15(3) of the Indian Constitution, which currently guarantees special provisions to women and children.

In Tamil Nadu, the AIADMK government added trans people under the MBC quota in 2017, roughly three years after the Supreme Court’s National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) versus Union of India judgment asked for them to be treated as a “socially and economically backward class”.

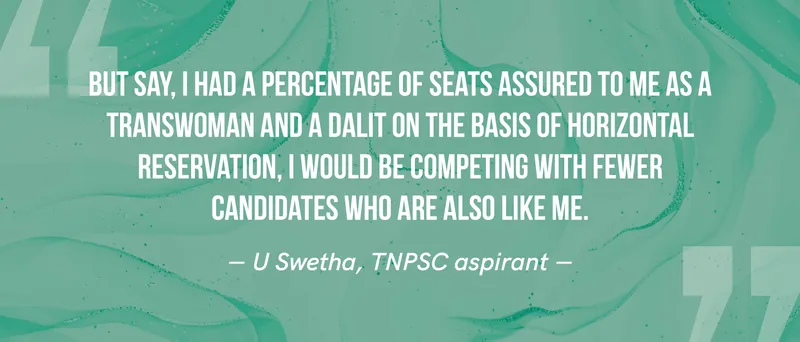

In this case, MBC is a vertical category, and a transwoman such as Swetha—who belongs to a Scheduled Caste—will require more advantages (like a specific number of seats allotted to her both as an SC candidate and a transgender woman) to increase her chances of getting a post.

Swetha secured 210 out of 300 marks, with an overall rank of 70,885. Her communal rank—which a candidate holds within their particular caste or community—was 11,575.

“This pitted me against thousands of male and female SC candidates and minimised my chances of getting selected,” says Swetha.

“Just as women don't compete with men, and vice versa, a trans candidate cannot compete with men and women,” says Banu. “This, especially becomes critical when it comes to physical examination in uniformed services.”

A legal win

In March last year, Justice M S Ramesh of the Madras High Court, made a strong recommendation to the Tamil Nadu government to provide a specific percentage of special reservation to transgender people in public employment, besides the concessions extended to the socially and economically backward classes.

In his judgement, Justice Ramesh, while hearing a petition filed by transgender candidates challenging the recruitment process for Grade II police constables conducted by the Tamil Nadu Uniformed Services Recruitment Board (TNUSRB), concluded that bringing transgender candidates under the 30% reservation for women—without an exclusive provision—could not be considered ‘reservation’. But the six trans candidates who won this case still remain unemployed.

This wasn’t the first time the Madras High Court expressed solidarity for a special reservation for trans people in public employment. Individual wins, such as that of Prithika Yashini who became Tamil Nadu's first transgender police officer in 2017, and S Swapna who became India's first transgender gazetted officer in 2020, were results of hard-fought court battles.

In October last year, the Madras High Court directed the Tamil Nadu Health and Family Welfare Department and Director of Medical Education, Chennai, to consider trans candidate S Tamilselvi as a member of the 'third gender/transgender' community and add her to a special transgender category for admission to a nursing course, for which the merit list was issued only for female and male candidates.

She had a similar dispute—the post-basic nursing and psychiatry nursing courses had communal reservations but no separate reservation for transgender candidates.

And, much before this in 2018, Justices C T Selvam and Satish Kumar of the Madras High Court had held that age relaxations permissible to ex-servicemen and destitute widows in public employment, should also be extended to transgender persons.

The court directed TNUSRB chairman to keep a post vacant for transwoman candidate Aradhana (then aged 27). In 2020, the age limit for transgender candidates was extended from 26 to 29 years. But, four years on, Aradhana still hasn’t gotten hold of that post.

Dalit-trans activist Grace Banu has been pioneering the fight for horizontal reservation for the trans community in Tamil Nadu in education and public employment

“We came to know that TNUSRB had gone for an appeal on that judgement,” says Banu, adding the community has filed a petition for contempt of court, but hearings aren’t happening.

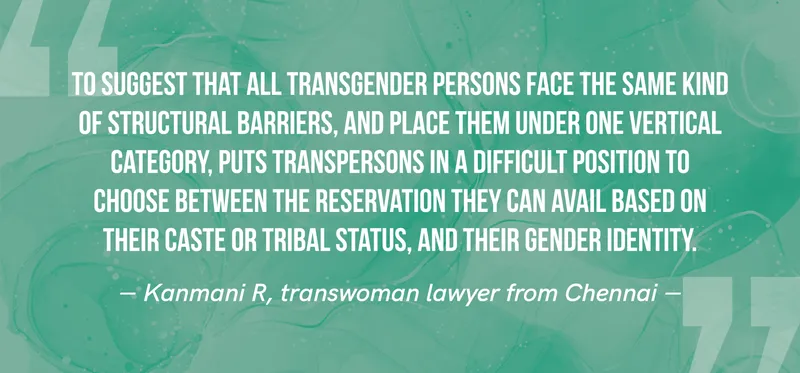

Advocate Jayna Kothari—who won the case for 1% horizontal reservation for the transgender community in Karnataka—observed that horizontal, compartmentalised reservation for education and public employment wouldn’t just take into account intersectional identities but also allow dalit OBC trans persons to not give up their caste identities while asserting their SC/ST and OBC status for reservations.

Becoming ‘qualified’ is the first of many battles

A 2017 study by the Kerala Development Society, Delhi, and the National Human Rights Commission, reveals that, while “in principle, the caste system cannot be applied to transgenders after joining the hijra community (which is a kinship system)”, some NGOs have revealed sporadic instances of caste-based discrimination.

This often reflects in the livelihood activities trans people within the system take up. Dominant caste trans members always choose to visit homes during weddings, childbirths, and auspicious occasions, middle caste members are involved in begging, and oppressed caste members must often resign to sex work, says the report.

The field survey in Delhi and UP also showed that no trans person had a job in the private sector, the government, or in NGOs at that time, and that more than 90% of them were deprived of employment opportunities.

This is an outcome of the longstanding issues young people from the trans community have been facing—abandonment, sexual abuse, bullying, violence, and expulsion from their families at a young age—causing lifelong scars on their mental health.

Most candidates from the trans community summon tremendous will and courage to take up government exams with the hope of a better livelihood and a secure future. They need to present their community certificates as proof to avail of benefits reserved for their community—whether they belong to SCs/STs, or MBCs.

Currently, this system hinges on getting authorisation from their natal families, which Banu says, is detrimental to those who have been cast out of their homes. “It forces them to revisit that very systemic trauma they are trying to escape, and that is unfair,” says Banu.

Aradhana, for instance, dropped out of school after class eight, following extreme gender dysphoria and emotional trauma. Before she turned 15, she left home to get a gender reassignment surgery and spent the next six years struggling for money. She finished her class 12 at the age of 22 when she started working at a restaurant.

It took Aradhana another three years to get her gender changed in her mark sheets and prove she was an MBC candidate. It was no surprise then, that she was 27 years old when she wrote the TNUSRB exam. “How can the age restrictions placed on male and female candidates be applied to someone like me?” she asks. “The reason I want to get into the police force is also to demonstrate the contribution of the transgender population to this society, and pave the way for the next generation of youngsters from my community so they have it easier than us,” she says.

On the other hand, Swetha was fortunate enough to find a free coaching centre to prepare for the TNPSC exams after moving to Chennai. But she found out she was HIV+, owing to years of sustaining herself through sex work. When Swetha appeared for the exam, she was extremely unwell and facing discrimination at every step.

This nature of inequity is compounded by the lack of understanding of the difference between ‘sex’ and ‘gender’, says Gopi Shankar, an intersex activist from Madurai and member of the National Council for Transgender Persons. In 2013, Gopi was among those who fought for Swapna, who wrote the civil services examination as a ‘female’ candidate.

In TNUSRB, the concessions currently given to women candidates in physical examination are extended only to the trans people who identify themselves as ‘female’, and not to those who identify themselves as ‘male’ or others.

“There is no enumeration of the number of people living with diverse sex characteristics and gender identities. Grouping everyone—including transmen, intersex people, and transwomen under ‘male’ or ‘female’ categories in examinations and job applications—is a matter of concern,” says Gopi.

He suggests a more nuanced approach of introducing an ‘others’ category, under which trans and intersex people can enroll, and decide the ‘gender’ they want to represent. It is also one of the key positions Kothari had taken while asking the Karnataka government to implement horizontal reservation for trans persons.

She had said at an international conference, “...that reservations should not be on the basis of medical diagnosis but rather self-identification,” so that every aspirant at every point of the spectrum gets a chance to live and work as equals.

(Creatives by Nihar Apte)

Edited by Suman Singh