Decolonising therapy: Mental health experts find ways to heal generational trauma in the Indian context

New-age mental health professionals talk about how to navigate complex family dynamics in the Indian context and break out of generational trauma.

(Trigger warning: domestic violence, generational trauma)

Before co-founding Guftagu—a Navi Mumbai-based counselling and psychotherapy service—in 2018, Aryan Somaiya worked for two years at a non-governmental mental health helpline that received close to 150 calls a day.

Many of the callers were women from low-income groups in Maharashtra, and a common trigger underlying these calls was familial discord. Some had been assaulted by inebriated husbands or were on the verge of a mental breakdown.

“Interestingly, as opposed to being rescued from the violent environment at home and taken into a shelter, they called in with a clear expectation that we have a dialogue with their husbands, find ways to stop the violence and teach them how to protect themselves,” Somaiya tells SocialStory.

The colonial understanding of any relationship—filial or intimate—as a fairly transactional equation built on agency is born in privilege, where Western therapy-inspired concepts such as ‘red flags’ and ‘boundaries’ have been built into the discourse. However, in a country where oppression has and continues to defend deep-rooted social, cultural and economic polarities, these concepts do little to resolve long-standing generational trauma, believe new-age mental health professionals.

Somaiya, for instance, was well aware that he was speaking with these women for the first, and possibly, the last time.

“Irrespective of whether the man in the household was acting in domination or not, I kept aside my own values as a queer-positive feminist and engaged with him as I would with a child,” says Somaiya. “My aim was to show him how he could communicate his displeasure through words instead of actions, and as a result, de-escalate the situation at that moment,” he says. “We also initiated partners to ways they could express their distress and disagreements nonviolently."

Somaiya’s long-term approach to therapy would involve going back in time with the violent partner to see where violence against women was normalised in his family. “Did he watch his father do it? Was it the movies he grew up on? These are pertinent questions I must ask,” he asserts. “Sometimes, the man in the house has not even thought about, or had an opinion about these things.”

Decolonising mental health in India

Simply put, decolonising mental health translates to developing nuanced interventions that work in and for societies that have a history of colonisation and racism, and where oppression often plays a role in indigenous, black and brown people’s mental health.

After graduate school, while working with communities on the ground, Neha Bhat—a sex-positive, arts-based mental health professional—was able to see that Instagram pop therapy or conventional Western therapy didn’t quite make the cut in the Indian context.

“Western therapy may tell you that if someone causes stress in your life, take a step away from them. But if you live in a household where you do not have the financial independence to move out or create divisions in the family, what do you do?” she asks.

In the Indian context, the concept of boundaries can be much harder to navigate, because displeasing someone here can be enmeshed in class and caste systems in a way that the Western world does not understand.

“A client of mine in an intercaste marriage told me that his mother-in-law (from a dominant caste background) is very picky about her space and vegetarianism while he and his wife love eating meat,” says Bhat.

In this case, not only did the three members have to navigate life living in a one-bedroom apartment during the COVID-19 lockdown, but the mother-in-law had also helped fund the man’s (who was from a south Indian Dalit background) MBA when no one else did. She had, as a result, become a safety net of sorts for the couple.

“The Indian context, like many Eastern contexts, is highly relational. People are each other’s ‘safety nets’ as well as their biggest oppressors here, and have been that way, long before we learned that it was our government’s job to be our safety net,” says Bhat.

In this particular case, the man followed all the mainstream mental health accounts on Instagram but was shaming himself for not finding the ‘perfect boundary’ with his mother-in-law.

Decolonial therapy is often understood as the most humanistic way to put the power back into an individual’s hands. In this case, it involved helping the family reflect and find rooting and unity in their own individualities.

“We stepped in to see how we could empower this family to create its own rituals. We looked at how to diffuse the idea of religious trauma that came with their inter-caste marriage, did discussions on what religion and spirituality meant to each person, and as a result, cultivate better interpersonal understanding,” she says.

Whether and how a family is suffering can be evaluated using German psychotherapist Bert Hellinger’s ‘Principle of Order’.

Hellinger taught that an indication that a family system was suffering was that its members were acting ‘out of order’; the youngest siblings acting like the oldest; parents looking down on their parents, and children behaving like parents to their parents.

“There are so many reasons why this can happen,” says integrative coach Nick Werber. “And the younger generations are just reacting to what has gone unresolved or left unaddressed in the family line,” he adds.

Finding autonomy in conflict

According to a 2018 study by the Indian Psychiatric Society, the family is a key resource in the care of patients in India, as its culture of interdependence gives it a preeminent status. It can therefore be extremely rewarding for families to collectively seek help.

In families that aren’t open to this idea—as is often the case in the country—finding your own rhythm amid the chaos is the way to begin healing, says queer-affirmative somatic psychotherapist Sneha Rooh.

“Many people can't leave families with generational trauma—whether it is sexual, financial, physical or emotional. They may be single children and/or have old parents who need support. They may not have the financial backing to move out. The reasons could be many,” she says.

Rooh had a client whose mother often compared her body to her daughter's and shamed her for not getting married or having a child because that would alter her body.

“Addressing generational trauma is doing shadow work (a process of self-exploration and self-acceptance aimed at confronting, acknowledging and embracing the hidden, often uncomfortable, aspects of oneself to achieve personal growth). You look at your family from an objective place and learn that they are separate beings,” she says.

Cultivating the awareness to identify the trauma in the family line is just the first step. Next is operating with yourself to identify parts of yourself and others that are instrumental in perpetuating the trauma cycle, and have remained unresolved over generations.

“You may do this by reinforcing to yourself over and over again what your own values are, how they differ from your family’s, and taking ownership to build your life based on them—even as you continue to share space with your family,” says Rooh.

Communicating boundaries can look different in each context, culture, family and relationship.

“Boundaries are meant to increase your ability to connect while making sure you can take care of yourself. A good version of a boundary includes you and is not centred on another person,” says Bhat.

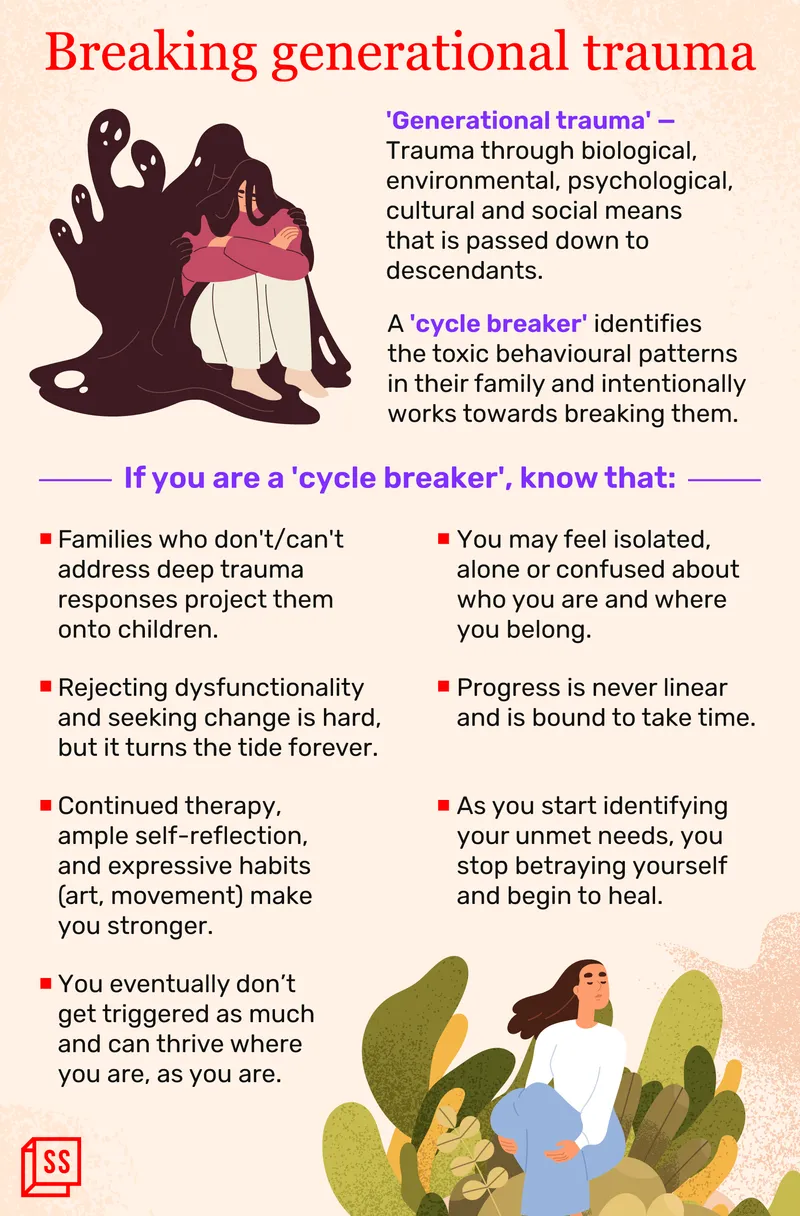

As Hellinger points out, the family ‘cycle breaker’ often experiences guilt, but eventually feels the most freedom from its traumatic patterns.

“It will take time and it will take energy. But it is possible and it is worth it,” says Rooh.

Edited by Kanishk Singh