Dastangoi - the ancient art of Urdu storytelling, on the road to revival in India

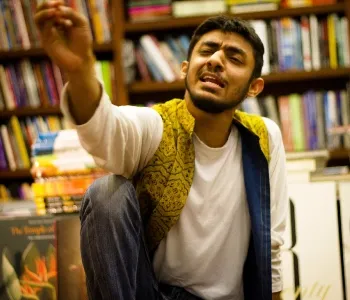

Dastangoi is an ancient Urdu oral storytelling art form, which had died down by early twentieth century. Thanks to some brave and talented researchers and skilled young storytellers, the art form has come back to life. We celebrate 10 years of its revival with one of the youngest dastangos (storytellers), Ankit Chadha - an entrepreneur, writer and researcher.

The art form originated in pre-Islamic Arabia, and was extremely popular between sixteenth and nineteenth century in India, especially among the rich elites and commoners of Delhi and Lucknow. Over the early twentieth century, with shrinking audience and even less dastangos, the art died down. The last known dastango was Mir Baqar Ali, who passed away in 1928.

माया मरी न मन मरा (neither desire nor the mind is dead)

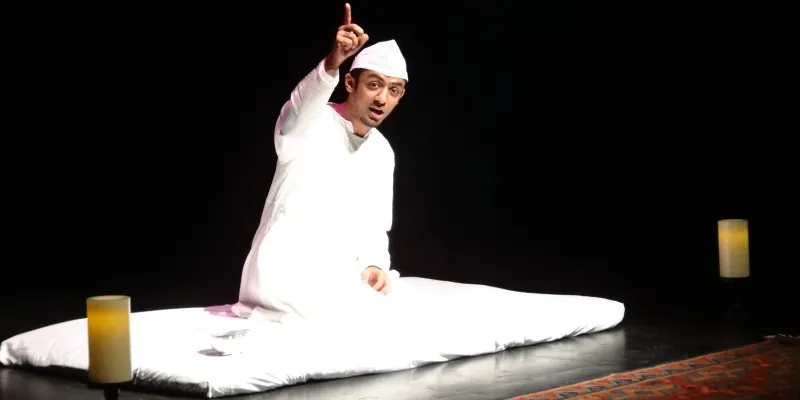

The long lost art form was revived in 2005; thanks to the famous Urdu poet and critic Shamsur Rahman Faruqi; his nephew, writer and director, Mahmood Farooqui; and his students. Forward ten years, and these dastangos have narrated their mystical and fascinating stories to audiences across the world. And being an art form that needs very little arrangement and setup, their dastangoi has witnessed audiences from typical proscenium venues, to university spaces; from dinner theatres to the maagh mela of Allahabad; from literature festivals to protest rallies; from corporate shows to community-run cultural ventures.

With the beautiful art form of storytelling gaining momentum, we celebrate ten years of its revival, and chronicle the story of Ankit Chadha - one of the youngest and most talented dastangos. He has a keen eye for history and marketing, and believes art is a form of entrepreneurship - with innovation at its centre.

तिनका कबहुँ ना निंदये (never blame a twig)

Ankit found passion in storytelling and street theatre while pursuing his graduation in Hindu College, at the University of Delhi. It was during these years, as the president of Ibtida - the dramatics society of his college, that he found his voice. His early writings explored issues like unemployment, consumer awareness and displacement. It was during the same time, that he started practising and performing his own writings, too.

After graduation, Ankit worked in a corporate marketing job. He was still writing, but mostly promotional material which was more boring than the projected fascination of ad copy writing. Although he gives his formal job, the due credit for developing his marketing skills, introducing him to work ethics, and teaching him the discipline involved with writing.

गुरु गोविंद दोनों खड़े (teacher and almighty both stand before me)

It was almost after two years in this job, that Ankit stumbled upon an event page on Facebook. This was the first Dastangoi workshop conducted in Delhi by Mahmood Farooqui and Danish Husain - in June 2010. Ankit was the youngest participant at this workshop. While mere acquaintance to the form during those three days motivated him enough to give it a shot, what followed was a journey very personal at different levels.

I had never thought of becoming a dastango. It was never the plan. Like all the best things in the world, it just happened. The way love just happens. Similar to street theatre, here was an art form that did not require lights, sounds, properties and stage to be arranged. It was just the story and the storyteller. This minimalism is what attracted me to this form. And the fact that it can become the medium to express a variety of content which moves me, is why I continue to practice it.

Ankit believes that art is a form of entrepreneurship with innovation at its center. Dastangoi, as an enterprise, had already travelled 5 years when he joined it. Shamsur Rahman Faruqi contributed with his extensive research. Mahmood Farooqui helped with concept and direction. Mahmood's wife and the director of Peepli Live, Anusha Rizvi helped them with design, and Danish Husain's performance had made a mark already. Ankit's marketing background helped. To begin with, he knew that he wanted to focus on a new range of products - contemporary stories, under the umbrella of 'brand dastangoi'. This work had to be promoted in new places such that the brand found new audiences.The most beautiful part of my journey is the relationship I share with my ustaad (Mahmood Farooqui), at whose residence all our rehearsals and baithaks took place. Director is just one of the caps he wears. For a person like me who had no knowledge of Urdu, his company is a blessing. Just listening to him has made me take a step towards discovering this language. His affection and deep connection with each student restores the guru-shishya tradition. There have been moments when I have got stuck, and one mantra from ustaad has showed the light. He's like a father who does not hand over books to his son, but keeps them at places where the son will eventually find through struggle.

माटी कहे कुम्हार से (earth speaks to the potter)

For the next 2 years, Ankit performed episodes from the traditional dastan of Amir Hamza, the brave and adventurous uncle of Prophet Muhammed. He felt both comfortable and curious about dastangoi as an art form. While the comfort gave him the confidence in performance, the curiosity led him to explore the nature and structure of dastan narratives more deeply. He soon wanted to bring in new content to the form.Apart from the innate thrill he got from writing, what inspired him to experiment was Mahmood Farooqui's personal work, too. Mahmood had created Dastan-e-Sedition in response to the incarceration and trial of Dr. Binayak Sen, who had been working among the tribal poor in Chattisgarh for more than 20 years. In the form of this dastan, Mahmood had given Ankit a way to express on contemporary ideas using the traditional art form. Ankit used his learning to create a spoof on dastangoi in the dastan form.

While I was embracing modernism, the shadow of tradition remained. I was influenced by Kabir and Khusrau. Sufi thought had evolved into an inspiration for me. During one of my field research on remote connectivity and digital divide in Jhabua (MP), I realised the huge divide that exists between English speaking urban rich, and non-English speaking rural poor. Together, these range of experiences strengthened my belief in the power of oral tradition - the foundation of the art that I practise.

Around the same time, a client for whom he was blogging as a freelancer, attended one of his performances, and proposed that he work on a dastan on mobile phones. The novelty of this idea got him hooked, and his dastan received an overwhelming response. This was his moment of truth. It became clear that he must dedicate all his time to this form and work on new content. He quit his job and he became a full-time dastango.

कहत कबीर सुनो भई साधो (says kabir, listen with care)

Now that he had 24 hours to tell stories, he was propelled into a new space with much larger audience. Stories for children became one of his focus areas. Gradually his work started earning recognition.

However, Ankit quitting his job was not taken lightly by his parents. They wanted Ankit to become an IAS officer, and were now apprehensive of the instability he was moving towards. It was when his mother watched one of his most acclaimed dastan on Kabir - Dastan Dhaai Aakhar Ki - that she changed her mind.

Similar to the other great things in his life, Kabir too, happened without any planning. The organizers of Kabir festival had requested Mahmood to work on a dastangoi on the weaver poet, and Ankit was found to be the eligible person to do it. Mahmood had written and performed an immaculate dastan on Manto, which became the benchmark for any biographical dastan henceforth. It took Ankit years of research and writing to finally come up with his Dastan Dhaai Aakhar Ki.

Our art of storytelling is unique because it lies at the junction of history, literature and oral performance. Kabir was all of these. That made Kabir an ideal subject for dastangoi. Also, Kabir did not write down any of his poems. They have travelled to us through oral tradition. This allowed Kabir's character to flow into this form seamlessly. Kabir spoke of formlessness, and hence did not come to me by applying a formula. I was trying to write his story, and all Kabir told me was "Suno bhai sadho". It is when I started listening, that he started speaking to me. I have no formal training in performance, literature or language. But, Kabir told me that I didn’t need any of it. All I need to do is to listen to the inner voice. The weaver taught me how to weave stories.

साईं इतना दीजिये (god, give me so much wealth)

Ankit now performs more frequently. He writes much more. This has also made things better for him on the financial front. As a creative entrepreneur who chose to devote his time to the art form and make it his means for livelihood, Ankit knew that this was going to be a long-term investment. He believes that than the plunge itself, greater courage is needed in hanging in there with the belief that you are doing what you are meant to.

In a postmodern approach of pursuing his art form, Ankit believes in mixing tradition and contemporary ideas. While dastangoi will always have its roots in the rich past of the unparalleled gems of literature in Tilism-e-Hoshruba, Ankit's pursuit is to simply learn from this past, and make way for future. In this process, if ‘stories on demand’ is what makes the venture financially feasible and also more excitingly relevant for today's audiences, he sees it as a win-win situation. The beauty of this evolution is that it is based on collaboration - with academicians, musicians, members of the civil society, and anybody who believes that this form helps in telling a story that needs to be told.

धीरे-धीरे रे मना (slowly stay my mind)

Despite all the success and recognition, the love from his audience keeps him humble.

When you work really well in a corporate job, you get a bonus. Six months into full-time dastangoi, I earned something that four years of corporate career did not give me. One of my patrons and now a very close friend, Khushru, wrote me a letter saying, "Thank you for doing what you do." That meant the world to me. Many listeners have since come up to me and told me how my work is a service to our culture, our history, and our literature - something they find extremely meaningful.

One of the biggest achievements by the army of these creative storytellers is the successful foray into children as an audience, with ‘Dastan Alice Ki’ being the first of many productions to follow. Ankit is also working on a biographical piece on Abdur Rahim Khan-e-Khana'n, one of the 9 gems in Akbar's court. This is going to be his second dastan on a Mughal figure, after the recently concluded ‘Dastan Dara Shikoh Ki’, to mark the 400th birth anniversary of the prince.

The lesson I wish to share with peers exploring a similar career is to write their own story. This is possible only when we listen - identify the gifts we have, and the ways in which their sharing can maximize the joy we experience. This story will always be more powerful than the stories of Bollywood stars and cricketing icons which the market sells us.