Unsustainable losses will morph wallets into merchant aggregators. What does it mean for players like PayTM?

The announcement of launch of Unified Payment Interface (UPI), built by National Payment Corporations of India (NPCI), sounded a death knell to mobile wallets, as the new payment system will allow consumers or merchants to transact directly with each other. With unique digital identities given to each back account holder, transacting will be as easy as sending an email over a bank interface. These digital bank account identities will be linked with Aadhar, the digital citizen identification number, for authentication. Over time, mobile wallets will be made to look obsolete.

To add to the woes of mobile wallets, Reserve Bank of India has also mooted an idea of allowing interoperability between mobile wallets, where a consumer could transfer from one mobile wallet to another without being charged. Currently, the charge for taking money back from the mobile wallet and transferring it into the back account is four percent. “UPI will not just reduce commission structures, it will also bring in a lot of people into the fold of banking,” says Sharad Sharma, Co-founder of iSpirit, a think-tank in the IT industry.

However, all the above are conjectures at this point, because the UPI is not yet launched and it has to gather critical mass to wipe out the wallets business.

Why isn’t a mobile wallet viable?

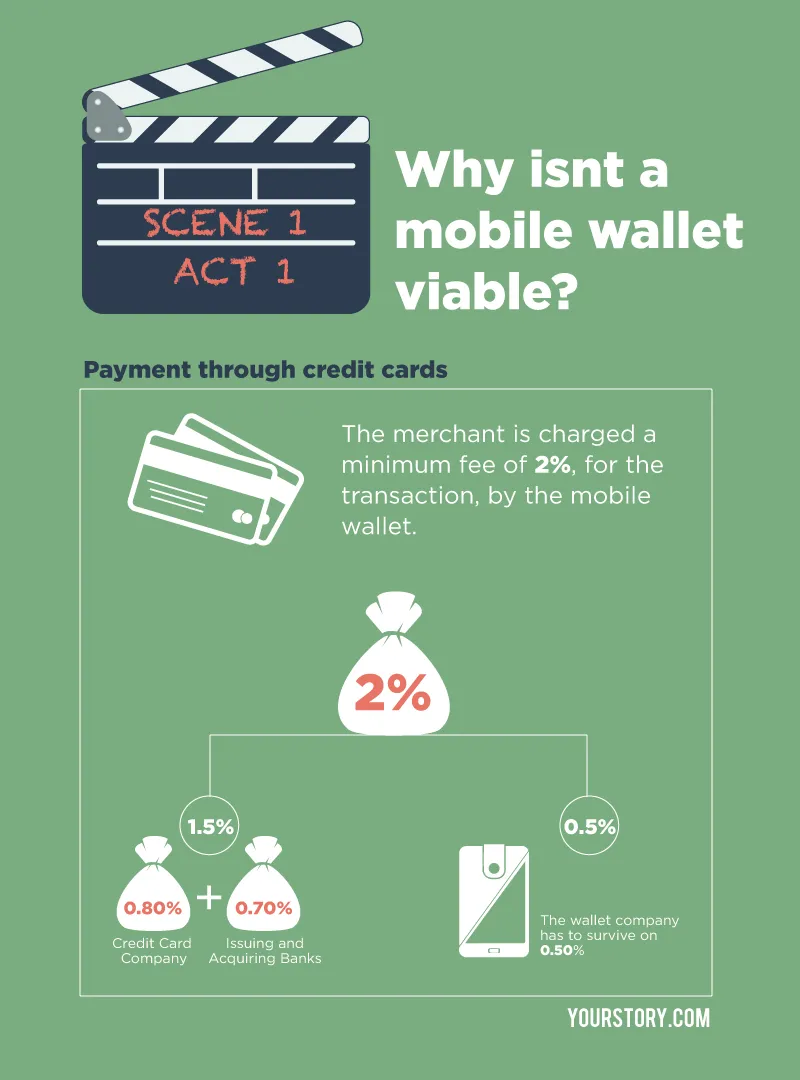

Scene 1 Act 1

Say, a consumer pays a merchant with a Visa or a Mastercard-branded credit card for a product. The mobile wallet charges the merchant a minimum fee of two percent for the transaction. This amount is used – by the mobile wallet - to pay the 1.5-percent charge that is split between the credit card company and the banks. Visa and Mastercard, which manage the transaction through their US-based switch network, take 0.8 percent of the 1.5 percent, and the issuing and acquiring banks split the rest. Technically, the wallet company has to survive on a revenue of 0.5 percent of the two percent charged to the merchant. With a number as small as this a mobile wallet cannot scale up operations because the costs are very high.

No wonder wallets like PayTM entered the e-commerce play to increase revenues. However, to acquire more customers, they had to discount purchases by offering cash-backs to consumers, and are currently sustain operations with investor money. That said, only four mobile wallets, including MobiKwik, will survive of the two dozen companies that have cropped up over the last three years.

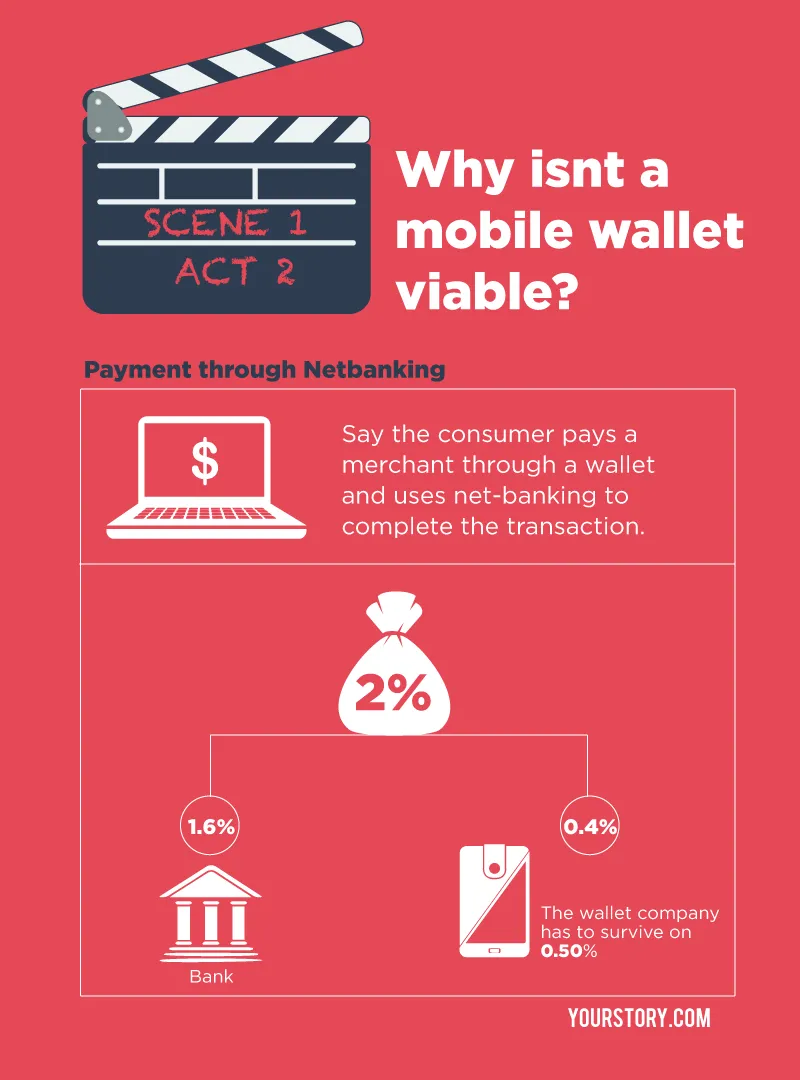

Scene 1 Act 2

Say, the consumer pays a merchant through a wallet and uses net banking to complete the transaction. Banks like ICICI Bank, SBI, HDFC Bank and Axis Bank handle 85 percent of the net banking in the country. Their charges are close to 1.6 percent, which again makes it unsustainable for wallets to survive with the two-percent margin. To make more money, they have to move away from consumer-led mobile wallet business. This would mean they would have to acquire merchants, and partner with startups that have already aggregated merchants for online-to-offline payment methods.

“The current commission structures are large. The RBI wants to bring down the charges and the UPI is going to do that for the country,” says M. Balachandran, Chairman, NPCI.

Why should mobile wallets move offline?

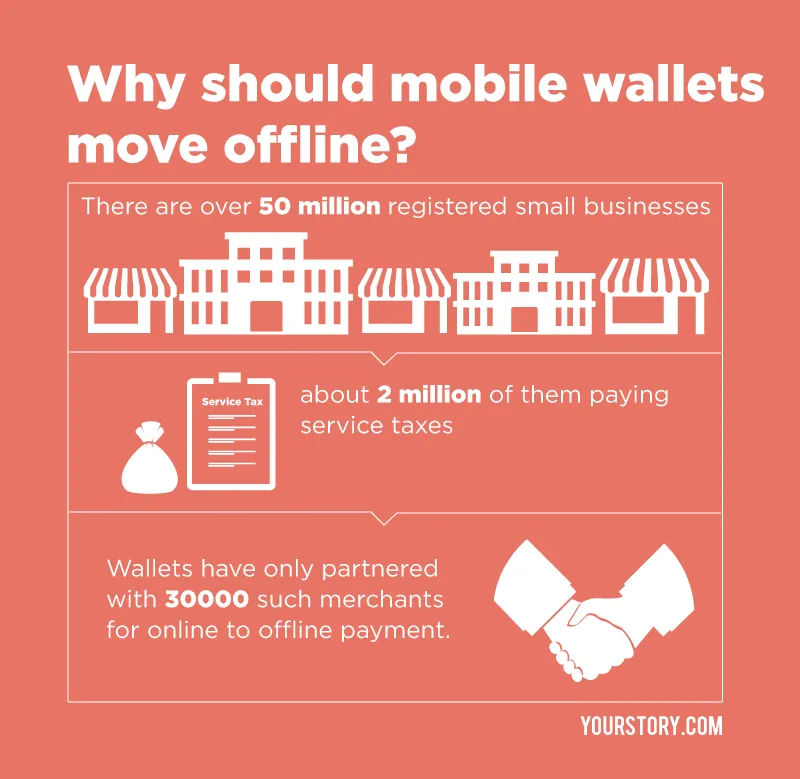

The opportunity of an online-app-to-offline payment is very large. There are over 50 million registered small businesses, two million of whom pay service taxes as their revenues exceed Rs 10 lakh annually. Wallets have only partnered with 30,000 such merchants for online-to-offline payment. Most experiments are happening in major cities like Delhi, Mumbai and Bengaluru. There are over two dozen wallet companies chasing the same bunch of small businesses and the small businesses are more than happy to entertain them because there are no charges involved. PayTM, which has more than 80,000 small merchants on its books, may naturally progress into enabling transactions with a mobile wallet in the store.

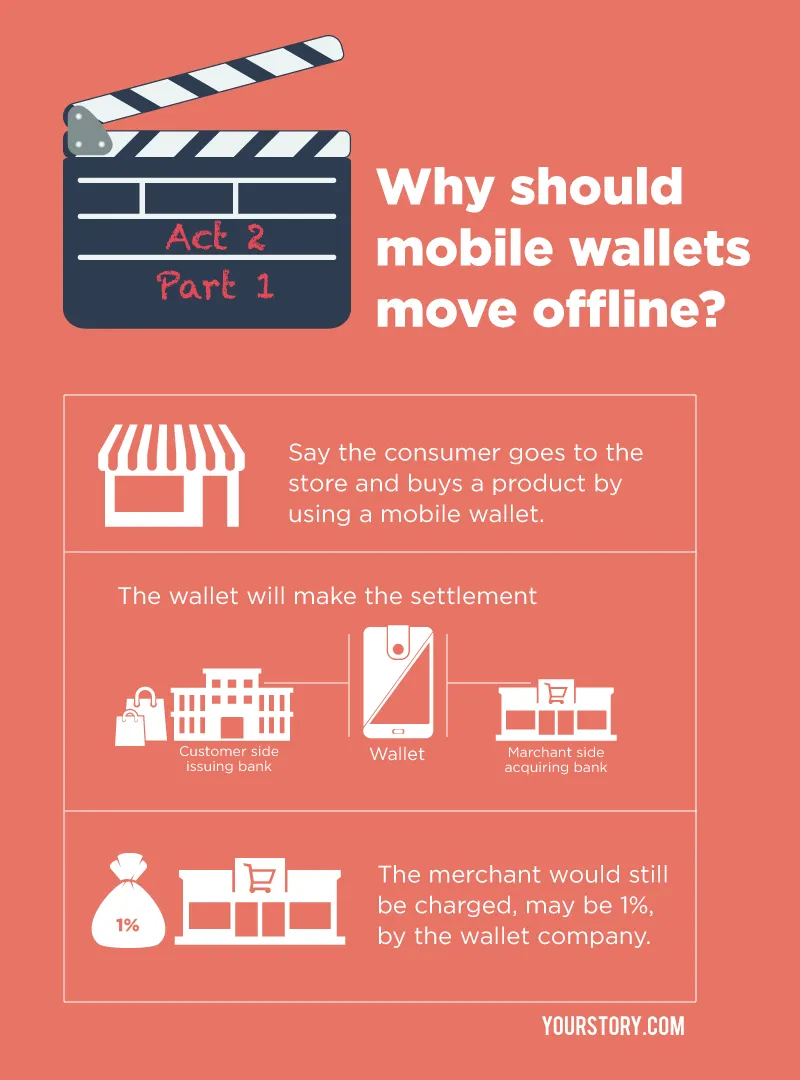

Act 2 Scene 1

Say, the consumer goes to the store and buys a product by using a mobile wallet. The invoice will be generated by the mobile wallet and payment details will go to the merchant. The wallet will make the settlement between the issuing bank on the consumer side and the acquiring bank on the merchant side. The merchant would still be charged, maybe a one percent, by the wallet company. But there is no intermediary, like a credit card switch or a bank gateway, involved, and the amount earned is with the mobile wallet. This business itself can be an expensive proposition because they have to acquire merchants. Momoe, the Bengaluru-based startup, has built its business on handling small merchant payments from consumers.

However, to continue with such operations the mobile wallet company would need a prepaid instrument licence, without which it is not allowed to hold money on behalf of the consumer. Or it should tie up with a bank.

It will not be an easy game for mobile wallets if and when the UPI system takes flight. PayTM's financials for the year 2014-15 revealed that the company’s losses were Rs 372 crore and it recorded revenues of Rs 336 crore. It has acquired close to 120 million users in the process of expansion.

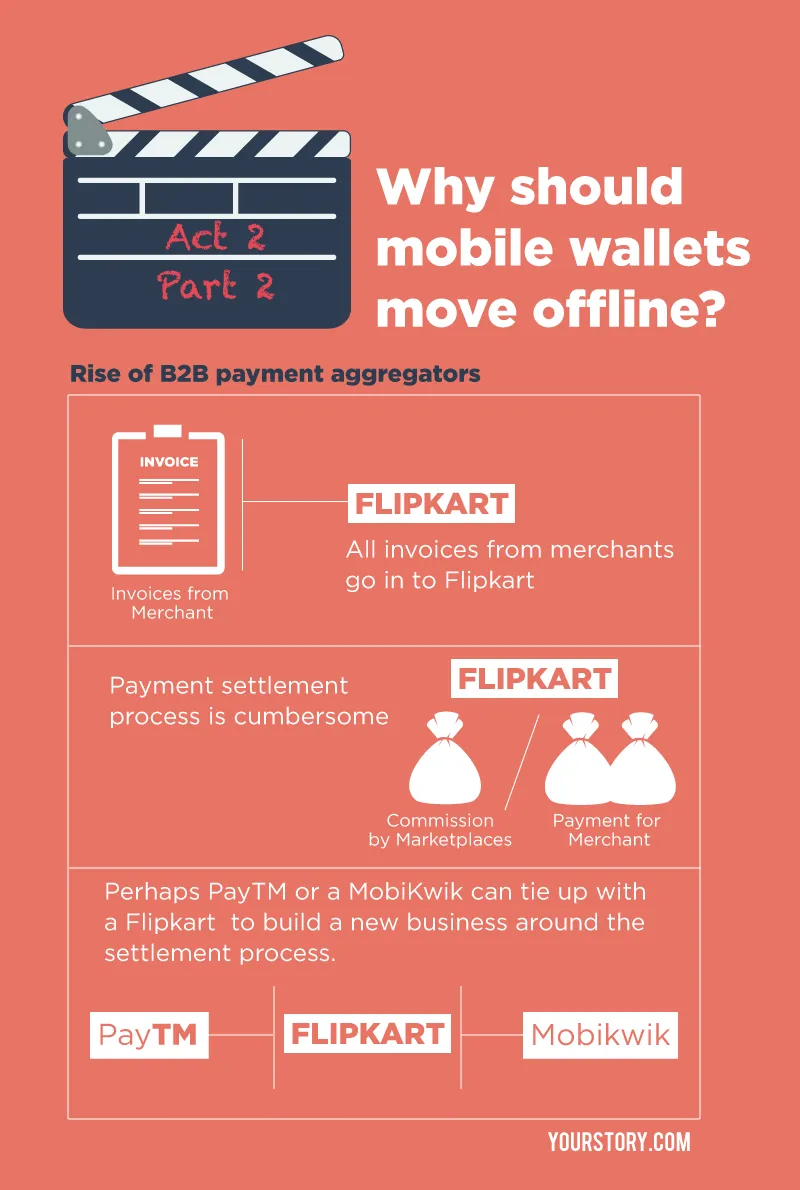

Act 2 Scene 2: Rise of B2B payment aggregators

Now the question arises whether mobile wallets will change their business model into aggregating payments between merchants and B2B businesses, because the B2C model has turned out to be expensive. Perhaps PayTM or a MobiKwik can tie up with a Flipkart and become their preferred merchant settlement app or gateway because of the two lakh merchants that transact on the marketplace. All invoices from merchants go into Flipkart and their payments are settled by the market place after deducting a commission. But the settlement process is cumbersome because of the myriad returns, reverse logistics and discounting procedures. This is where wallets could build a new business around the settlement process. However Flipkart and Amazon India have recently announced that they would also launch mobile wallets.

The question is, do they have the bandwidth to do merchant-to-merchant settlements?

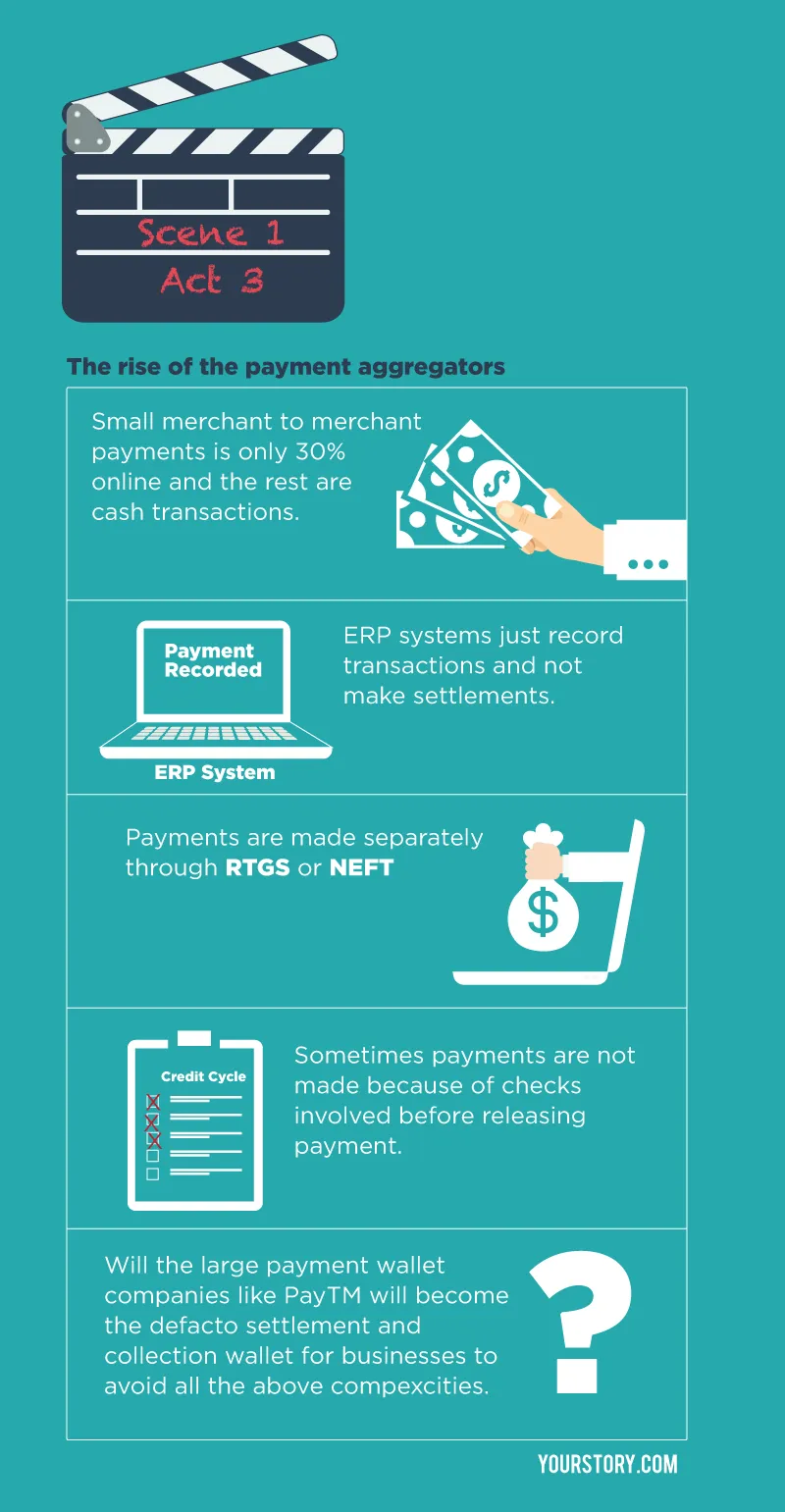

Act 3- Final Scene: The rise of the payment aggregators

Today, the consumer wallet business is becoming an acquisition game. However, the B2B payments mechanism is yet to be disrupted with technology. Today, in a city like Bengaluru, small merchant-to-merchant payments form only 30 percent of the online transactions and the rest are cash. Large corporates want to streamline their vendor payments systems beyond ERP systems, which just record transactions and not make settlements. Payments are made by an accounts team separately through RTGS or NEFT, based on credit cycles of companies, and sometimes payments are not made because of checks involved before releasing payment. The payment complexity arises because of batch processing of product, payment cycle on batches of products, tax reconciliations, change in product pricing, defaults of distributors and quality failures.

There are a couple of startups trying to reconcile all this into one system and could become the defacto settlement and collection wallet for businesses. Will the large payment wallet companies like PayTM attempt this bet? Only time will tell. At least for now it is clear the UPI will eventually kill mobile wallets and net-banking charges. That said, strange things are bound to happen. Maybe the system will co-exist with reduced commission structures. Surely Visa-Mastercard will now have to rethink their India strategy, which is why they are already aggregating smaller merchants by enabling them to accept mobile payments.