The hidden startup lesson I learnt from binge watching Silicon Valley

Doing the morally right thing every time is difficult for entrepreneurs facing crushing odds. But HBO’s hit show—and research on real-world companies—reveal that for those who do, the business gains are enormous.

[WARNING: spoilers ahead.]

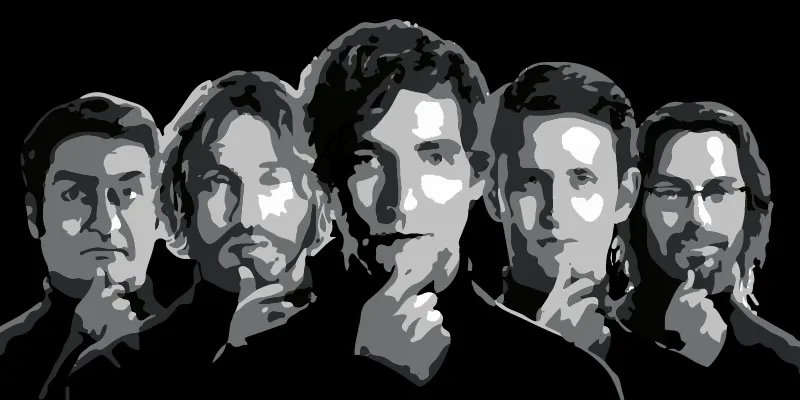

Last week, I binged on all three seasons of Silicon Valley, the hit HBO show on the adventures of four guys building a startup: a brilliant but managerially inept American coder who's booted out of the company he founded before staging a dramatic comeback; a Pakistani American coder who's a compulsive but luckless flirt; a Canadian coder who worships Satan; and another American who would do anything for the team but is treated like a doormat. There's also an American ex-entrepreneur who runs the incubator where said startup is housed but is better known as a weed-smoking, foul-mouthed albeit large-hearted idiot.

Basically, a show that's out and out about the American Dream, featuring stereotypes you can recognise from a mile away: the Heroic Geek, the Sexually Repressed Geek, the Anti-Establishment Geek, the Geek with Low Self-Esteem, and the Buffoon. (Here's a fun piece by a fan mapping all the leading characters against their real-life inspirations.)

Generally, shows of this type follow a predictable narrative formula: the entrepreneur's rise, a humiliating but temporary fall, and then the chastened entrepreneur's final, soaring resurgence. They bank on the comforting certainty of the triumph of the human spirit against powerful forces—you can't go wrong with David vs. Goliath. Last year, India got its very own startup show Pitchers, a web series produced by the new media company The Viral Fever, which followed the same formula and drew massive audiences as well as critical acclaim thanks to its authentic script and performances.

(Trivia: Pitchers is #25 on IMDb's list of the world's best shows. Silicon Valley is #171.)

But this past week, as I followed the exploits of Richard Hendricks, Dinesh Chughtai, Bertram Gilfoyle, Jared Dunne, and Erlich Bachman, I kept wondering: While shows like Silicon Valley charm the audience by playing up traits popularly associated with entrepreneurs—‘guys next door', 'socially awkward', 'dreamers', 'rule breakers', etc.—can startups in the real world actually learn anything from them?

Now, this is an area where one must tread lightly. Startup education is something of a scourge in the world that we live in. Everyone thinks they can teach something to startup founders, even people who have never in their lives built any kind of business. Actually, they more than others—this won’t endear me to my former media colleagues, but just look at all the expert commentary on startups by business journalists, most of whom have no idea what running a business and being responsible for people's livelihoods feels like. (Lest you think I am one of those pontificating pests, well, I did try founding a business once at the behest of a friend—a youth magazine that we thought would take Delhi University by storm. It's another matter that we sucked at being entrepreneurs.)

Given this mood, it can be dangerous to presume that a TV show, whose primary purpose is to entertain and not to educate, can teach anything at all to entrepreneurs. In Silicon Valley though, I did spot a pretty fundamental if understated lesson for entrepreneurs, though to get to it you need to look beyond the hurly burly of the plot and the nerdy jokes.

The biggest risk to a startup is the founder's inability to deal with moral ambiguity.

To be sure, ambiguity is an age-old concept in business management. It is one of the quartet of challenges that make up VUCA (Volatility, Uncertainty, and Complexity are the other three), considered any CEO's arch nemesis. Here's how Harvard Business Review describes ambiguity:

It's a pretty comprehensive description. Ambiguity is indeed the state of being surrounded by 'unknown unknowns'. However, this classical definition of ambiguity is too simplistic, being rooted in challenges that test only one dimension of leadership: strategic thinking. Look at the examples of ambiguity that HBR furnishes: moving into immature or emerging markets, or launching products outside your core competencies. These are the kind of things that B-School case studies are tailored for. Anyone can develop some sort of mastery over them through practice and experience—or, as the smartest CEOs routinely do, by simply hiring consultants.

Moral ambiguity, on the other hand, is a far more complicated dimension of ambiguity that cannot be taught in a classroom or outsourced to a suit. And it comes by default with the job of an entrepreneur. Arun Maira, who worked with the Tatas and headed Boston Consulting Group in India before becoming a member of the erstwhile Planning Commission, once told me that stripped to its essence, being an entrepreneur or innovator means being in a constant state of tension between the world as it is and the ideal world that only the entrepreneur can see in their mind. That tension is a necessary condition for creativity. Without it there is simply no reason for the entrepreneur to exist.

However, the tension also pushes the entrepreneur to militate against the way things are, to be in a hurry to knock down walls, to test the limits of socially acceptable behaviour, perhaps even break the law.

The entrepreneur is always at war—against the status quo, against a lack of resources, against competition. Everything's fair in that war, the entrepreneur believes, because ultimately they are fighting to make the world a better place. It is this bravado that keeps the entrepreneur going. In fact the entrepreneur often demands that society at large support them in breaking rules—including the prevalent moral framework. After all, it's all for the greater good.

In Silicon Valley, Hendricks, the founder of Pied Piper, a revolutionary data compression app that can transform all kinds of industries, from entertainment to health care, repeatedly faces situations loaded with moral ambiguity. In Season 2 Episode 5, he discovers that Bachman's incubator does not have the licence to operate as a business premise, making the whole setup patently illegal. A cranky neighbour who lives alone and moves around in a wheelchair finds out and threatens to tell the authorities. Faced with eviction, Hendricks resorts to blackmail. He photographs the neighbour with his pet ferrets, which are illegal in the state of California. The neighbour must keep quiet about Bachman's operation or risk prosecution himself. (The caption of that YouTube link is telling: It calls the neighbour a 'prick', because he gets in the way of Hendricks and Co.'s revolutionary rule-breaking.)

On the face of it, the trade-off between a business and someone's pet ferrets is an absurd plot device meant to invoke a few laughs. But it is also a sharp insight on what it takes to be an entrepreneur: holding on to absolutely anything just to stay afloat. Morals be damned.

There are two other, graver instances where Hendricks's moral compass is tested. In Season 2 Episode 9, he is asked by an arbitration court whether he developed any part of Pied Piper using equipment belonging to his former employer Hooli. As it turns out, Hendricks did indeed use a Hooli computer—once—to tweak Pied Piper's software. He must lie in court, else Hooli, a monster corporation that eats up everything in its way, will be granted ownership of Pied Piper per its employment contract with Hendricks. Hendricks is under intense pressure from his team to lie and save his startup, but he refuses to cross the line.

However, it is not a lasting moral victory for Hendricks. When it sinks in that Hooli is going to rob him of his life's work, he asks his team to destroy Pied Piper's algorithm. If he can't have it, no one can. It's only through a fortuitous ruling by the court, which declares Hooli's employment contract unenforceable, that Hendricks is able to keep Pied Piper. He rushes back to the office just in time to stop his team from going all kamikaze with the platform.

An even bigger test of morals comes when Pied Piper's daily active user number proves disastrously low. Dunne, ever the Man Friday to the team, commits the ultimate tech startup sin: he buys fake users from a sweat shop (technically known as 'clickfarm') in Bangladesh. Pied Piper needs to raise fresh funding or it'll go bust. Once again Hendricks has to lie and pretend the inflated user numbers are real, or his startup will fold (Season 3 Episode 10). Once again, he refuses to. I won't tell you what happens next, but suffice it to say Pied Piper manages to live.

What do the three episodes have in common? In two of them, the startup faces extinction not because its product isn't great—it is, in fact it is universally acclaimed as the hottest thing in town—but because it is blindsided or overpowered by external factors beyond its control: an unlawful incubator and a cunning, powerful competitor. On both those occasions, the temptation to bend the rules is immense, and Hendricks doesn't always do what is morally right. But every time he does, things always work out in the end, though it is doubtless a terribly difficult choice.

In the Indian startup ecosystem too, battle-worn entrepreneurs are increasingly impatient with the textbook definitions of 'right' and 'wrong'. In a recently published piece, a senior journalist-turned-entrepreneur questioned a telephony startup's implicit plea that breaking laws and regulations is somehow kosher, because those laws and regulations are "archaic".

Around the same time, we had one of our star unicorns resorting to jingoism to run down its competitor in a fierce legal battle. The high-strung, melodramatic statements by the company meant the press had a field day, but not many commentators believed it was either an honourable or a particularly mature ploy by the company to play the nationalism card in court—especially given that national borders mean nothing in the world of tech startups.

Then there’s the unseemly trend of startups leaving campus recruits high and dry. Market conditions are, well, dictated by the market, and it is no one’s case that startups should be forced to absorb excess hands when their business can’t support it. But if the accounts of the affected and the company’s alleged emails to them are to be believed, the manner in which they were abandoned by at least one of the startups stank of a shocking, cavalier lack of morals. You cannot hide coldly behind market forces while dealing with human lives. (Disclaimer: I haven’t independently spoken to these startups, but I do know of other startups that have hired some of the students left jobless.)

Yes, it is frustrating for entrepreneurs to be saddled with regulations from another era which make no sense today. Yes, impatience with business-as-usual is essential for an entrepreneur to survive and grow. Yes, a far stronger competitor willing to go to any lengths to crush you may tempt you to take desperate measures. And yes, market conditions can derail even the best-laid plans. But ultimately, like everything else in life, entrepreneurship is a choice. You can't choose the life of an entrepreneur and then complain that the rules of the game are unfair. And you cannot expect the rest of the world to ‘understand’.

It’s simple really;the world doesn’t cheer for those who win any way they can. A great example is the character of Frank Underwood from another smash hit House of Cards. Underwood reaches the chair of the American president by displaying a ruthless, singularly evil lack of morals. He is a winner if there ever was one, but he is also the most reviled character on TV these days. Or take the Australian cricket team. Historically, they are as successful a unit as you can get, and yet their rough, ultra-aggressive brand of cricket means they don’t fill fans outside their country with a warm fuzzy feeling. People root for you if you do right by your stakeholders—even if you lose. Think Hendricks, or the ever-popular West Indian cricket team.

The rewards for those who play by the rules when faced by morally ambiguous choices go far beyond good karma and fan love. There’s data that companies led by morally upright CEOs show markedly better business performance. In a survey documented by HBR, companies led by CEOs with greater moral strength—a composite of integrity, responsibility, forgiveness, and compassion—were found to do far better than the rest. They delivered an average return on assets of 9.35% over a two-year period. In contrast, companies with CEOs who scored lower had an ROA of 1.93%.

Still not convinced? Here’s Fast Company’s list of CEOs ranked by reputation. Look through the list, and you will see a striking if not universal correlation between reputation and business performance. (No surprises for guessing who brings up the worst CEO list: a certain Donald Trump.)

Reason enough for our returns-minded entrepreneurs and investors to ditch shortcuts and start doing what's right, every time?