Why this engineer from Bengaluru quit her high-paying job and moved to the remote mountain villages of Uttarakhand

I trek to the extremely isolated villages and live there with the locals. The taboos around menstruation are very extreme in the areas where I work. These areas follow some extremely archaic traditions, many of which are undocumented anywhere else. During their period, women drink cow urine and sprinkle it in their homes to ‘purify’ themselves, sleep in the cowshed with the livestock, sit apart, do not touch people, do not touch water directly, do not attend religious events, and have many more such restrictions. This is mostly because they are afraid of the ‘gods’. Menstruating women who have broken these rules are often blamed for lack of rains or for leopard attacks. Animal sacrifice is rampant and is performed to appease the gods.

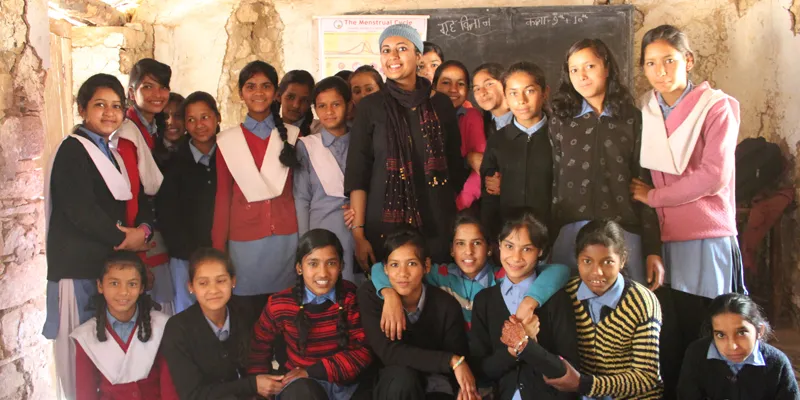

For the past nine months, Brinda Nagarajan has been trekking to some of Uttarakhand’s remotest villages and conducting workshops to increase awareness about menstruation among locals. The lack of information about a biological process like menstruation is disturbing, and she has found incidents like those mentioned above to be alarmingly common.

From a cushy office to the unforgiving mountains

25-year-old Brinda was a business analyst at a top global bank in Bengaluru until a few months ago, when she decided to quit her cushy job and explore a career in the development sector. Much to the surprise of those around her, Brinda took up SBI’s rural development fellowship, Youth for India, to work in the area of menstrual awareness and hygiene management.

A Bengaluru girl, Brinda graduated with a degree in engineering from SASTRA University, Thanjavur. After her graduation, she worked at Mu Sigma as a senior business analyst in the upcoming field of data science and analytics for two years. She then moved to HSBC for a year, post which she took up the SBI fellowship.

Although she hails from a Tam-Bram family, traditionally known to be a very rigid class, adventure was always in her blood all thanks to her liberal father.

My father is a broad-minded person and is extremely supportive of women and women’s empowerment. I feel privileged to belong to a family where I have always been told that men and women are equal and that I should never restrict myself because of my gender. Throughout our upbringing, both my younger sister and I have always been supported by our father in everything, be it solo travelling or motorcycling,

she says.

Hence, when Brinda made the not-so-lucrative decision of quitting her well-paying job in the prime of her career to take up a rural development fellowship which would cost her an 80 percent salary cut, her family was more than supportive. Her father, a chemical engineering and materials science alum of IISc Bangalore. is also helping her out with low-cost, 100 percent biodegradable sanitary pads. While family support came easily, there were a few who ridiculed Brinda for her decision.

“It was hard, but I stood by my decision.”

Taking on some serious challenges

What followed was an uphill task not just of spreading awareness about a taboo topic, but also adjusting to the difficult life in the mountains. There was no road connectivity and Brinda had to trek practically everywhere in sub-zero temperatures. Getting the locals to accept her was another challenge.

I spent more time living their life and doing everything they did on a regular basis. I started learning Kumaoni, dressing like them, learning their local songs, cooking on the chulha, working with them in the farm and with the livestock, and literally becoming one of them. Today, I am one of them and we have a lifelong bond.

Along with conducting workshops, Brinda is also working on a book on menstrual awareness specifically for the rural audience and is designing cloth pad-making workshops for which she is seeking funding. Although Brinda is now acquainted with most locals and their way of life, she is still working in extremely difficult conditions, battling with uncertainty almost every day.

Many a time I fear how people will accept me, or whether I might get thrown out of the village for speaking about such a topic. That is the extent of the taboos around menstruation in India — I literally fear for myself sometimes.

The taboos are innumerable and are a way of life for most women in the remote villages Brinda works in. Since these women have grown up in restricted environments, they have come to accept the taboos around menstruation as a part of life. These taboos are often inexplicably connected with God and fate, and hence are very hard to discard. This is why Brinda is extra conscious and approaches such situations with a mix of cautiousness, sensitivity, and modern science.

Although her efforts have often been met with a lot of resistance, she cherishes a few experiences like her introduction to Prema, a young orphan from the mountains who treks four hours every day to work and to support her younger siblings.

“Her hard work, dedication and the fact that she smiles through her pain is unparallelled. I have learnt and been inspired by her determination, hard work, and hope,” Brinda says

Why menstruation

Since a young age, Brinda had always believed in giving back to the country. 88 percent of India’s 355 million menstruating women have no access to sanitary pads. Women in rural India use old cloth, sand, ashes, and straw instead of sanitary pads. 23 percent of girls drop out of school when they start menstruating. In some places as many as 66 percent of girls skip school during this time and one-third of them eventually drop out. It was this lack of menstrual education and hygiene management that drew her towards working on it.

Having always been a passionate advocate for women’s rights and empowerment, I have noticed that menstruation is a topic that is largely ignored. Considering that this influences 50 percent of the population, the relative focus on the subject is dismally low,

she says.

But thanks to Brinda and others like her who are selflessly working towards bringing about change, the attitudes are definitely changing, something Brinda has also noticed over a period of time.

Most of the younger generation might still live by the traditions, but they have started questioning them. Especially with improvements in education and awareness on menstruation, more and more women are questioning what they do and the many taboos around menstruation. This realisation and questioning is a big step towards changing the attitude, but we still have a long way to go before they can be eliminated.

At present, Brinda is concentrating on her work in Uttarakhand and is awaiting her book being published as well as the funding to take the cloth pad workshops ahead. She wishes to move into social entrepreneurship at some point in the future and use her experience in big data and analytics for social good.

And no matter how tough the going gets, she is ready to take it on with a smile, all thanks to the life lessons she has learnt through this experience.

After living in a place where landslides and cloudbursts are as common as the venomous snakes and scorpions, where electricity, toilets, roads, and phone signal are a luxury, and where many times you do not know what tomorrow has in store, I have started living one day at a time and being thankful and grateful for each day.