One month since demonetisation, what have we overlooked?

Vivek Kumar, who sells clothes at Delhi’s famous Sarojini Market — where Rs 100–500 is the average price, has had poor business in the last one month. “Daily sales have become less than half of what they used to be. People do not have Rs 100 currency notes, and change has never been harder to come by,” he says.

Vivek is not the only one. Since Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched what he calls a "surgical strike" on black money in the country by banning currency notes of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000, the common man has been plunged into misery despite a majority applauding the move.

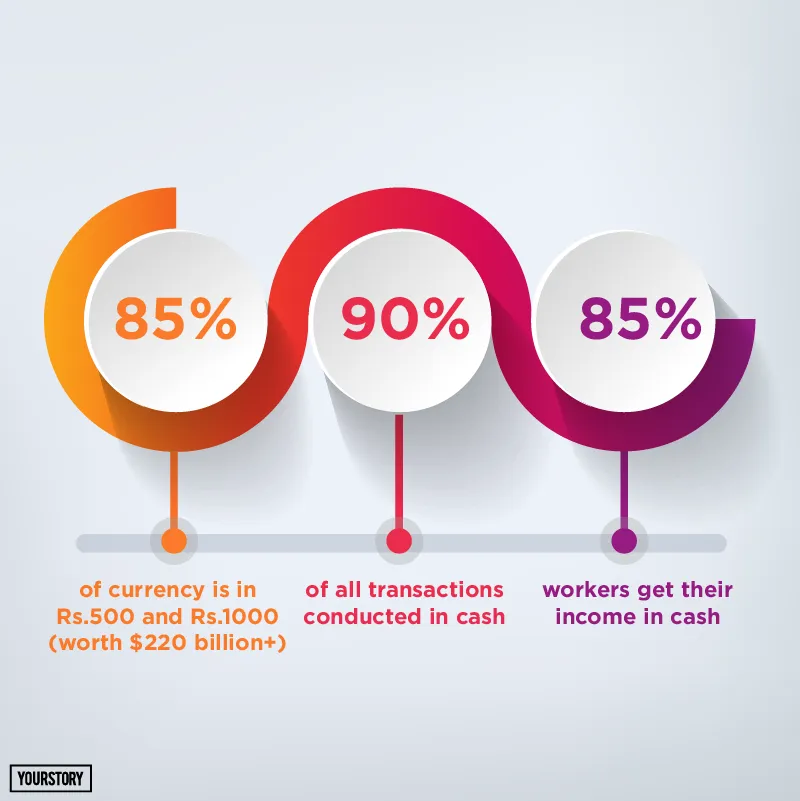

The announcement, which banned the currency from the midnight of November 8, was immediately followed by long queues outside ATMs and panic at hospitals and for wedding preparations. Within no time, the informal retail sector was crashing, and those with no bank accounts (leave alone plastic money) were losing out on their daily wages. New currency notes of Rs 2,000 were not useful for their daily expenses, as nobody had change. Online payment, however, suddenly gained popularity. Paytm’s traffic has risen by a whopping 435 percent since November 8.

While there is hope that this move will pave the way for financial inclusion, the plan seems to have too many glitches. Many experts — from former Prime Minister and economist Manmohan Singh to ex-RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan — have been critical of this move. Social media, as it does for any news, has been divided about the demonetisation, as is mainstream media.

There have been allegations that Modi timed this move, targeting regional parties’ funding right before the Uttar Pradesh election. A journalist, who has keenly observed rural affairs, said: “In rural villages, local parties often take 1–10 percent of the selling price for services like land registration. This money will be in trouble now.” The opposition doesn't even have enough money to mobilise people for protests.

However, the demonetisation move is not disapproved of by the local population. Prof GK Karanth, Head of the Centre for Study of Social Change and Development at the Institute for Social and Economic Change, explains the psychology behind this. “If the state is bringing the black money out, the villain is the one who perpetuates it. Even if it causes hardship, they are glad that those guys are punished.”

What is black money?

In simple terms, any money which is unaccounted for is black money. The untaxed money which is kept away from Indian banks, as well as fake currency notes, come in this category. Although accurately predicting its magnitude is impossible, various reports estimate the incidence of black money to be between 25 and 75 percent of GDP.

According to Prof Karanth, the Indian economy is driven by the power of black money. “The consumerism we saw in the last 10 years was because we had money coming from additional sources. A professional can show profits from farm as income,” he says.

Contrary to public perception, black money is rarely stashed. It is mostly spent on gold, real estate, and foreign currency. In fact, Income Tax raids of 2012–13 on undisclosed incomes showed only 6 percent held as cash. (The World Bank estimates that 20 percent of India’s GDP is black money, which comes up to around Rs 13,000 crore.)

According to a study by the International Statistical Education Centre, about 5 percent — that is Rs 400 crore worth of currency — out of Rs 17,00,000 crore in circulation is counterfeit. With sophisticated technology on both sides, it won’t be too hard to counterfeit again. In fact, there are already reports of counterfeit notes of the newly released Rs 2,000 currency being circulated.

There is a tendency to print higher denomination notes because the cost of printing is much lesser than the value of the currency. According to a report in Livemint, the cost of printing a currency note as a percentage of its value is higher for notes of lower denominations. For example, the cost of printing a Rs 10 note is almost 10 percent of the value of the note whereas the cost of printing a Rs 100 note is less than 2 percent of its value.

Flaw in the plan

The demonetisation move reportedly was ‘planned’ for the past six months. But there is a glaring question: why did the government not ensure that there was enough currency in lower denominations to compensate? After all, there is no law preventing printing of notes abroad.

Well, Rs 2,000 notes would help remonetise the economy faster. Smaller denominations would have taken longer to print, and getting cash exchanged from banks would have demanded bags rather than purses.

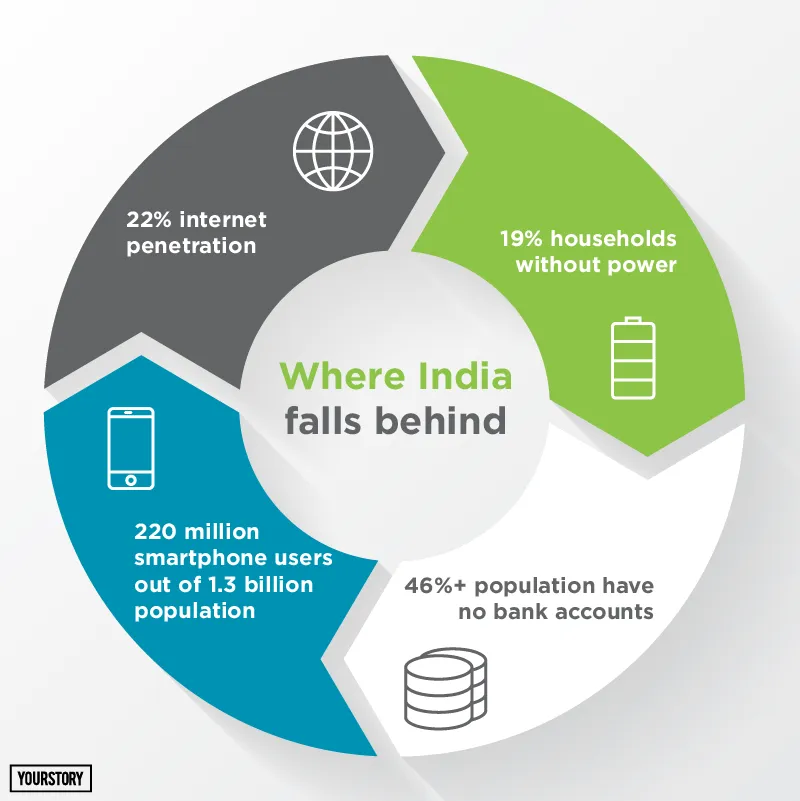

In a perfect world, the currency ban would have led to wages and payments being credited to bank accounts directly. But India is nowhere near that. Former Finance Minister P Chidambaram has stated that India has no capacity to print more than 300 crore units of currency in a month, while the current withdrawal rate is seven times higher.

The high inflation over the past few years has ensured that Rs 500 is a “high-denomination” currency used only by the rich. Also, a higher denomination like Rs 2,000 will only make it easy for black money hoarders to stock up large amounts.

Complaints about not being able to access their hard-earned money is not just among the population active on social media. Rural women who kept their savings as cash — without going to banks fearing alcoholic, abusive husbands — are also now left penniless.

Additionally, co-operative banks — where most farmers and poorer sections of the society have their only bank accounts — have been stopped by the RBI from transacting with old currency under suspicions of enabling money laundering by the rich.

For the greater good?

Reports suggest that there has been a 60–70 percent dip in unorganised retail, which is 90 percent of the total retail in the country. Perishable stock has been troubling small vendors and wholesale dealers as almost all of these purchases are done in cash. Renowned economist Jayati Ghosh, Professor at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University, recently wrote in The Hindu that this has affected production systems, “as moneylenders providing working capital to small producers are unable to provide the new notes.”

Needless to say, farmers can’t sell crops without cash either. When prices fall, farmers take the hit. In Bihar, cauliflower, which was sold for Rs 12 per kg before the currency ban, is now being sold for Rs 1. For daily wage labourers as well, this move has brought about nothing but chaos.

At the same time, Prof Karanth says consumption patterns are also changing. “Either you have to cut down on even the daily essentials, or since units of consumption cannot always be in Rs 500 and Rs 1,000, a compulsory consumption is imposed as there is no change available,” he explains.

Abundance of loopholes

When it comes to depositing the demonetised currency notes, loopholes are many. Although a ceiling of Rs 2,50,000 has been set for depositing in the bank, it is set for each PAN card. The problem lies in the fact that an average household would have three or four accounts. If four adults in a family can deposit Rs 2,50,000 each in the bank, it is easy to cover Rs 10 lakh black money. “Beyond a point, the government will not be successful in bringing them to book. There is a cap on the success,” Prof Karanth says.

There have even been reports of petrol pumps, hospitals, and temples converting black money from hoarders for a small commission, by creating fake receipts or showing the amount as anonymous donations to the temple.

The other target behind demonetisation — to curb counterfeit currency and fight the finances to terrorism — is, well, a bit too ambitious. Prof Suresh Jnaneswaran, Director of the School of Social Sciences at the University of Kerala, says: “This is only a temporary paralysis to the finance to terrorism; the reasons behind terrorism are not touched. Counterfeit currency is part of international warfare. It flows from across the borders and will continue to do so for Rs 2,000 too.”

A critique of capitalism?

The Central Statistical Office (CSO) estimates that informal sector contributes to 50 percent of India’s GDP. This informal economy is dependent entirely on cash. With the currency ban, the stakeholders of this economy, the rural poor, are in a grim situation — poor infrastructure, lack of education, and inaccessibility to e-banking restricts them from accessing their own savings. However, efforts by the central government for financial inclusion have seen results in the past one month.

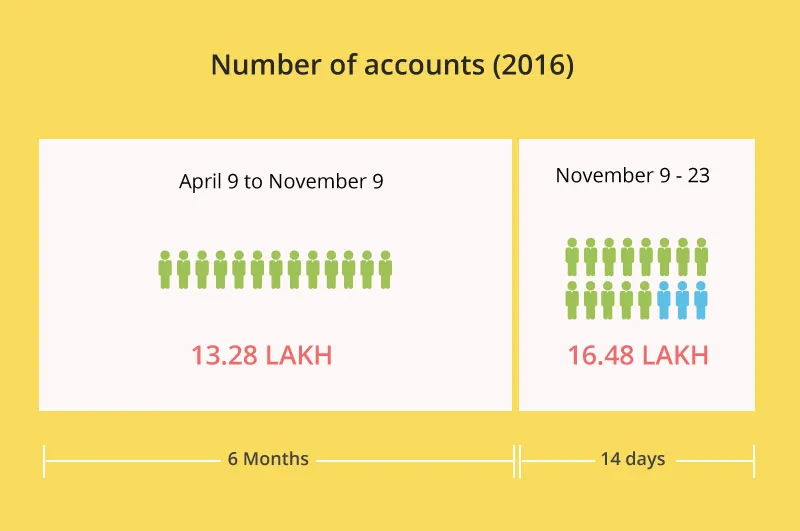

In August 2014, the‘Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana’ was launched for building financial inclusion in the country, hoping to make financial services more accessible to the population. Two years since its inception, the PMJDY had become irrelevant. But from the day after demonetisation was announced, Jan Dhan accounts have seen about 50 percent surge in deposits, a development which has aroused concerns of black money holders using such accounts to deposit their money through existing account holders and/or starting new ones.

Alternate paths

On November 29, a day before India published its GDP growth in Q2, global rating agency Fitch lowered our growth forecast for 2016-17 to 6.9 percent from 7.4 percent. Their report suggested that lack of cash to complete purchases and disruption in supply chains has paralysed farmers. “The impact on GDP growth will increase the longer the disruption continues,” it said.

Of course, wide cynicism has happened among the people during land reforms and nationalisation of banks, and when privy purse to the royal families was abolished. Demonetisation will surely make a dent in the existing system of distribution of wealth. But this is not a cure-all move.

While appreciating demonetisation in general, Karanth warns that the present success shall be sustained only if specific measures are taken up. “One of them is agricultural taxation. Just as we are digitising money, work also has to be accounted for, whether as an agricultural labourer, a cobbler, or a software engineer.”

As idealistic as this might sound, honest administration is the only way out. Tax department officials need to operate without interference. Prof Jnaneswaran says: “The issue here is law enforcement, not demonetisation. There is no insulation against counterfeit because it is always in demand. Or else, we will have to do demonetisation every two years, which puts too much pressure on the people.”

After all, surprise attacks are a part of wars — but against the enemy, not your own people.