Seven tips for entrepreneurs from Jack Ma and the Alibaba story

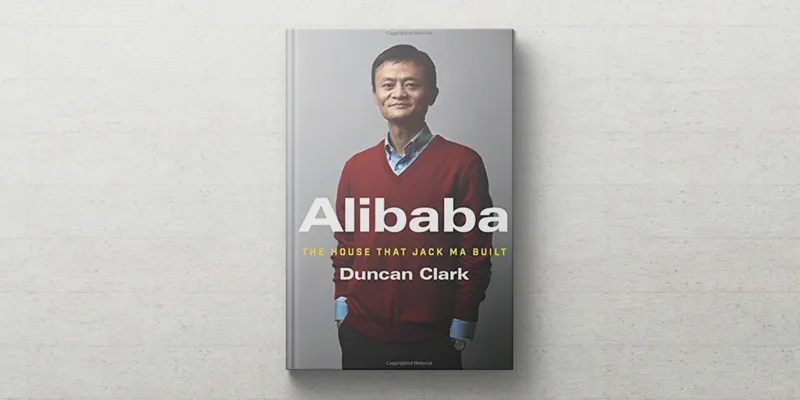

The engrossing book, ‘Alibaba: The House that Jack Ma Built’ is an insider’s account of how an English teacher in China built one of the world’s most valuable companies, rivaling Walmart and Amazon. The rise of Alibaba from startup to giant in less than 15 years culminated in a $25 billion IPO in 2014, the largest global IPO ever.

The author Duncan Clark founded BDA Consulting in Beijing in 1994, and first met Jack in 1999 in the small apartment where Alibaba was founded. He served as an advisor to the firm, and draws on a wide range of sources for this informative book. Duncan was formerly with Morgan Stanley, and has lived in China for over 20 years.

Here are my Top Seven takeaways and tips for entrepreneurs from this 287-page book, in terms of the context of e-commerce in China, Alibaba’s strategy and culture, competitive positioning, and future growth. See also my review of the related book, China’s Disruptors: How Alibaba, Xiaomi, Tencent, and Other Companies are Changing the Rules of Business by Edward Tse.

Build an innovation ecosystem

“Over 400 million people, more than the population of the US, make purchases on Alibaba’s websites each year,” according to Duncan; this accounts for two-thirds of all parcel deliveries in China each day.

The company’s strengths are built on the ‘iron triangle’ of e-commerce, logistics and finance. Its marketplace websites include TMall (branded products), Alibaba (international B2B trade), TaoBao (local e-commerce), and Juhuasuan (Groupon-like site).

It has invested in premier logistics firms such as Shentong, Yuantong, Zhongtong and Yunda; most of their business comes from TMall and Taobao. Payment provider AliPay is expected to generate almost $5 billion in revenues by 2018; it has also created an online mutual fund, Yu’e Bao (becoming the fourth largest money manager in the world within 10 months). The new business Sesame Credit Management provides credit ratings to third parties.

Build an innovation culture

Alibaba has built a culture of camaraderie and commitment. Employees are called ‘AliRen’ (‘the Ali People’), and the anniversary (May 10) is celebrated as ‘AliDay,’ which celebrates teamwork and achievements. Lessons from hardships such as the SARS crisis are shared, and mentorship is strongly promoted. Employees are encouraged to learn from setbacks, but without ‘shame and blame.’

The culture is informal, and employees are encouraged to adopt a nickname. Employees can avail of interest-free loans for housing. The company’s culture is codified in the Six Vein Spirit Sword: customers, teams, change, integrity, passion and commitment. Employees are frequently rotated between regions and roles to broaden their experience. Former Alibaba employees have been associated with 317 startups (as compared to 294 from Tencent and 223 from Baidu).

Be a master storyteller

Jack Ma is regarded as a masterful speaker, and networks with the giants of the business world. He has been described as a ‘Rockefeller’ of his age and even ‘Don Quixote,’ and a mix of ‘Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, Larry Page and Mark Zuckerberg, all rolled into one.’ He has also been nicknamed ‘Crazy Jack,’ and his charisma is called ‘Jack Magic.’

Unlike many Chinese entrepreneurs who returned from US education and work stints, Jack describes himself as ‘one hundred percent Made in China.’ He has a strong ability to ‘charm and cajole,’ and is ‘attention-grabbing in both English and Chinese.’

Quotable quotes (‘a soundbite machine’) and humour are hallmarks in this maverick’s talks, and Duncan jokes that Jack Ma could be a ‘stand-up comedian’ as well. As storytelling and culture-building techniques, Jack uses references, imagery and metaphors from Chinese martial arts characters. (See also my review of the related book, The Storyteller’s Secret by Carmine Gallo.)

Understand the local context

In Jack Ma’s early years, formative developments were the reforms of the Deng Xiaoping era. He grew up in Zhejiang, China’s ‘crucible of entrepreneurship’ in the Yangtze River delta, with Shanghai as its centre. The Yiwu wholesale market was an early template for Alibaba, and Wenzhou was home to the country’s first private railroad and air carrier. The General Association of Zhejiang Entrepreneurs may be ‘the largest business association in the world.’

The collapse of the Soviet Union followed by the rise of the Internet shaped the Chinese government’s cautious approach to dealing with the online world – promoting digital infrastructure while controlling media expression. “China wanted a Silicon Valley, but one that it could control, built on its terms,” Duncan observes; this would manifest in the ‘Great Firewall of China’ as content filters.

Early Internet players in China, some with US exposure, include AsiaInfo, UTStarcom and the portal players Sina, Sohu and NetEase. The dotcom crash of 2000 and the financial crisis of 2008 would rearrange the pecking order of the different waves of China’s digital startups.

Today, Jack Ma stands “at the intersection of China’s newfound cults of consumerism and entrepreneurship,” Duncan observes. Due to pressure on urban land, inventory and rental costs are high - and retail offline penetration is lower than in large countries like the US. Thus, e-commerce is a necessary channel for many categories and has become a lifestyle. “More than 40 per cent of Chinese consumers buy their groceries online as compared to just 10 per cent in the US,” says Duncan. Young mothers are also a key customer base for Alibaba.

Accept the cycles of boom and bust

Jack was born on September 10, 1964, the Year of the Dragon. His parents shared a passion for folk art performances. As a boy, he developed a love for the English language and literature, which would help him develop an international outlook and network with visiting tourists. He developed a friendship and professional association with one such Australian tourist, David Morley, who became an angel investor in the company.

A visit to the US exposed him to the Internet, and he launched his first online venture China Pages, moving out of his teaching days (his other venture was Hope Translation services). He later moved to Beijing to work for the trade ministry; a formative meeting was with Jerry Yang, founder of Yahoo, during his China visit. Jack’s next venture would be Alibaba, for which he roped in Taiwan-born investor Joe Tsai as co-founder.

Early competitors would be the websites of the trade magazine Global Sources, and MeetChina. The NASDAQ IPO of China.com in 1999 opened the international floodgates of the consumer Internet investment boom in China. Jack Ma’s ambitions rose to position Alibaba as a global player, attracting early investment from Goldman Sachs and Softbank (Masayoshi Son would be regarded as a ‘kindred spirit’ for Jack Ma).

Be prepared to take on the giants

The growth of the international market attracted larger players like Yahoo and eBay. eBay bought a stake in Chinese player EachNet, and Alibaba responded by launching Taobao and AliPay with new investment from Softbank. eBay fumbled with wrong cultural approaches to its China strategy and design, and eventually withdrew.

Yahoo entered the China market with a Chinese PC manufacturer as partner, and later bought a firm called 3721 Network Software; Jack Ma negotiated a deal to sell 40 per cent of Alibaba’s stakes to Yahoo for a valuation of about $4 billion. Other entrants such as Google exited the China market due to security and censorship concerns.

The road ahead – plan for the bigger picture

The ‘BAT kingdoms’ (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent) are major Internet players in China today. There are notable local competitors to Alibaba, such as JD.com (with an ‘asset heavy’ strategy like Amazon), and chat-based commerce from WeChat (the app launched by Tencent).

Alibaba is investing heavily in startups in China in mobile, media and crowdfunding spaces (the book does not cover its investments in other countries like India). It also has a research wing, AliResearch, and has launched rural initiatives such as e-commerce kiosks as well as a global consumer operation called AliExpress. (See also my review of the related book China Fast Forward: The Technologies, Green Industries and Innovations Driving the Mainland’s Future by Bill Dodson.)

Concerns have arisen, however, over the investment and holding patterns in the web of companies controlled by Jack Ma. His activities as entrepreneur and philanthropist have expanded to grappling with China’s greatest challenges, in reforming healthcare, education and environment.

It would be fitting to end this review with one of Jack Ma’s popular quotes: “Today is brutal, tomorrow is more brutal, but the day after tomorrow is beautiful.”