Niche online marketplaces say they will thrive even when the Flipkarts and Snapdeals struggle

A handful of startups are out to prove that differentiated, scalable and profitable online marketplaces can be built in India without spending billions of dollars

Vinanti Kothari makes beautiful wood-based lap desks, and cushioned trays to keep laptops, or even a cup of tea on one's lap. Late last year she became a seller on LoveThisStuff, an online marketplace focussed on fashion and home décor products made by small designers. Her brand, NotSoShabby, has sold over 200 pieces of lap desks and other décor items, priced between Rs 400 and 3,500, on LoveThisStuff since January. That is a remarkable number, as Vinanti makes all her products by hand on her own and until getting on LoveThisStuff she had showcased her products at just a couple of exhibitions.

LoveThisStuff is among a few unique marketplaces that have sprung up in India to connect small makers and designers with consumers who do not want mass-produced products. Sites like Qtrove, Engrave, Kraftly, LoveThisStuff and Tjori are multi-category marketplaces, but operate very differently from Flipkart, Amazon and Snapdeal. Most have raised only a few lakhs to a couple of crores of funding. While India is home to thousands of ‘makers’ like Vinanti, and millions of consumers who want to buy the hatke products they make, can such platforms become large, scalable and profitable ventures? This question is especially moot at a time when the sustainability of platforms like Flipkart and Snapdeal, which have spent billions to build up their firms, is in doubt.

While each of these e-commerce sites have their own focus, talking to the people who run these businesses reveal a common mindset and also a shared set of principles and practices.

Products bring differentiation

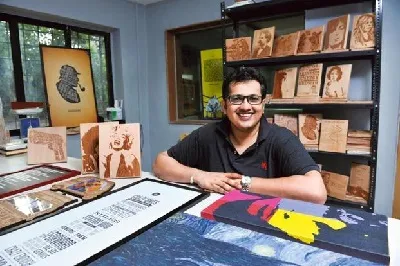

If Amazon, Flipkart and Snapdeal are mostly about commoditised, mass-produced and branded products, then these sites are about unique, mostly handcrafted creations. Nimish Adani, founder and CEO of Mumbai-based Engrave, says questions on sustainability of e-commerce models are very valid. Nimish, who launched the marketplace in 2015, says:

These questions are valid not just for Flipkart and Snapdeal. I ask myself that question every day. Amazon is out to eat everyone's lunch. If we can answer the question of what it is that sets us apart, then we can succeed. We are a maker’s market and Amazon is not going to change its business model to become one."

The focus is on showcasing products that are not available on other marketplaces. Engrave, which has over 600 active makers on its platform, focusses primarily on handmade crafts, with categories like customised nameplates and engraved plaques making up a significant chunk of its offerings and sales. The company is targeting a revenue of over Rs 3 crore this fiscal and aims to double it the next fiscal. Unlike the larger e-commerce companies, Nimish means earnings only from commissions when he talks about revenue.

LoveThisStuff curates small designers from across the country, primarily in categories like fashion and home décor. Qtrove also curates the products on its marketplace and focuses on handcrafted products just like LoveThisStuff, but the emphasis is on local merchants and on a broader spread of categories ranging from F&B to pet care. Incidentally, both are promoted by GrowthStory.

Kraftly, launched in 2015 by the founders of e-commerce seller services SaaS platform KartRocket, is a consumer-to-consumer marketplace selling everything from party supplies to fashion created mostly by homemakers, small designers and craftspeople.

Seller is king (and queen)

It is all about the seller, the maker or the designer for these marketplaces. “We do almost everything for the seller. He or she just needs to focus on design,” says Vatsala Kothari, founder of LoveThisStuff. The condition for a seller to list on LoveThisStuff is that they should be the designer and creator of the products. The designers can create a shop within LoveThisStuff with a Facebook-like dashboard, upload photographs of their products, set the price, decide whether they want to put some of their catalogue on discount, and update the stock. The marketplace provides them an order management dashboard and also gives them a one-click link to logistics providers. LoveThisStuff charges a 15-percent commission from all sellers. While the Bengaluru-based marketplace was founded in July 2016, the site was launched in September, and marketing started in January. The platform, which has over 300 designers, has notched up GMV of Rs 50 lakh in five months.

“Since we are a smaller marketplace, our sellers get better visibility. The bigger marketplaces want to promote products that are available in quantity. But we have limited inventory – our products are one-of-a-kind, some are manufactured to order,” says Akshay Gulati, Chief Business Officer of Kraftly. The site has an active seller base of 20,000. Sellers are free to sell products for a few months, de-activate and then come back after a few months to sell a fresh batch. The company declined to share revenue or sales numbers.

While marketplaces like Amazon, Flipkart and Snapdeal require sellers to have a minimum number of products to sell, these alternative platforms allow sellers to list any number of items they want.

Also, a small seller is part of the ‘long tail’ for large marketplaces, ensuring variety but not really a focus for the site. On the smaller marketplaces, these sellers are the focus and even become the centre of marketing campaigns.

Vinanti of NotSoShabby says she prefers a platform like LoveThisStuff as they provide handholding for the seller and promote the designer and her brand. “They even created a separate lap desk category under home décor, making discovery of my products much easier,” says Vinanti (26). She says she will not list her products on Flipkart and Amazon as she makes limited number of stock, given that everything she sells she makes on her own.

Feel good factor

These marketplaces target a ‘more evolved’ group of customers, a set of people who are well-travelled, understand the importance of buying directly from the maker, and look for sustainable, natural or organic products. They also do not want to buy the same bag or kurta that a thousand others own. The goal of these platforms is to make the customer feel good about themselves when they shop.

“Our customers are not just buying a bookmark; for them the story behind the bookmark is important,” quips Nimish of Engrave.

Another ace they hold is the ability to customise. Both LoveThisStuff and Engrave allow personalisation in many categories like nameplates, canvas prints, plaques, bath linen, travel accessories and stationery.

The entrepreneurs running these startups say the market for such products already exists and is sizeable. The numerous exhibitions—like Soul Santhe—in metros and their success is proof of that. While there is no reliable data on the size of the market for non-mass produced or handcrafted products, the market size for organic food can be an indicator.

A study by industry body Assocham and non-government organisation TechSci Research estimated that the market for organic food is currently at $500 million, and will grow by three times in the next four years. Etsy, a US-based online platform for handcrafted goods that is the inspiration behind the Indian alternative marketplaces, is a listed entity, with a market cap of almost $1.5 billion.

While the customer base may be big getting them online is the challenge as these marketplaces are still only getting the word out. Unlike their larger peers, these platforms do not discount and do not do mass marketing. Brand and marketing expert Meeta Malhotra says their 'niche-ness' can be an advantage in marketing. Meeta adds:

When you are a niche player, the big advantage you have over the horizontal Goliaths is that you can have laser-sharp focus on your customer and craft your marketing strategy accordingly. They (the Goliaths) have to be much more generic because they need to appeal to everybody."

This is exactly what they are doing. Qtrove’s Vinamra Pandiya says he continuously tests out different types of digital campaigns and advertisements to see what is most effective. “We did category-wise and price-wise ads on Facebook and Google; we also customised our campaigns according to demography. We also use our data. If you have bought organic honey today we will send an automated email in three weeks’ time saying, 'replenish your honey',” he says.

Responsible growth

While the larger marketplaces are focussed on GMV, the smaller players are focussed on sustainable growth. This is clear in the metrics they track. Akshay of Kraftly says 'orders fulfilled', 'active sellers on the platform', and 'repeat order rates' are the important metrics for Kraftly. Qtrove’s Vinamra is targeting to be operationally profitable by this year end. “We want to be sustainable and profitable, and have been unit-positive from day one. We charge 25-30 percent as commission from sellers and they are paying. We charge customers for delivery and they are paying too,” he says. Qtrove ships over 400 orders a day and the average ticket size is around Rs 600. The target is to reach 1,000 orders a day in around three months.

K Ganesh, Serial Entrepreneurs and Partner at GrowthStory, says this is not a winner-takes-all market, and there is space for 3-4 differentiated marketplaces. “Customer interest is very high, so demand isn’t an issue. Companies that use technology instead of operations and humans to connect buyers and sellers will do well,” he says.

That’s what these companies are doing. Most have lean teams—Qtrove’s team size is 10, Engrave’s is 18—and use automation for everything, from invoicing to emailers.

Some are even trying different business models. For instance, Delhi-based Tjori started out as a marketplace in 2013. The idea was to bring handcrafted products not just from India but also other geographies for an Indian audience. In 2014 the company experimented with a small private label collection. The response it got gave founder Mansi Gupta the confidence to expand Tjori’s in-house designs. Today Tjori’s in-house collections range from Morocco-inspired embroidered boots to Turkey-inspired metal coffeeware and tableware. While the site still has products of other sellers, its in-house collections account for 70 percent of sales. “The economics works well and we are able to control quality and quantity,” says Mansi, who works with about seven production units across the country to get the products made. Tjori provides the raw material and design and the units make to order, so the company does not have to bear inventory costs. As a result, most orders take 7-10 days for shipping. Tjori sees around 400 orders a day, with an order value of around Rs 2,600, and has operationally broken-even.

While these companies are focussed on profitable growth, will they become large marketplaces? Or are they just acquisition targets for the biggies? Ganesh of GrowthStory says that the overall GMV or sales will not match that of an Amazon or a Flipkart but that does not mean these will be small players. “There is Future Group and there is a Manyavar too. The same customer will go to both. One is a commoditised branded play, from whom a customer will get 80 of his monthly buys, but for the rest 20 percent the customer will go to these other marketplaces. They will be more profitable and scalable,” he says.

Finally, it is all about the ambition of the founder. Says Nimish of Engrave:

I believe we can be a multi-billion-dollar marketplace. The Bombay Store, Fabindia, Good Earth may be niche, but they are large businesses in their own right. I am not here to build a niche business.”

(With inputs by Athira A Nair)