Over 1 lakh women and counting: the rise of super women in sex workers, and how an NGO made it possible

Swasti, an enabler more than an NGO, has provided a platform for female sex workers to put their foot down and raise their voices. Saying NO to clients who refuse condoms and fighting cases of violence in courts are just some ways in which these women have become fiercely independent. They are proving that sex workers are no longer synonymous with victims.

Sex work in India is spoken of in hushed voices, if spoken of at all. The multitude of women involved in it, therefore, are wrapped in thick layers of stigma and locked away. The number we are talking about is anywhere between 1.25 and 3 million women in sex work, as estimated by the National AIDS control program III and the Ministry of Women and Child Development. This staggering difference is indicative of the research that is yet to be conducted in this matter; but diving into the depths of taboo means talking about it first.

Swasti, a not-for-profit health resource centre based in Bengaluru, has not only been talking about it, but has also been transforming the smog-like negative atmosphere around sex workers, for 15 years now. Sex workers fall under the umbrella of high risk individuals in the contraction of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, along with drug abusers, transgenders, and men who have sex with other men.

While trying to achieve public health outcomes for these socially excluded and poor communities, Swasti realised that a health intervention involving only awareness programmes on HIV/AIDS is nowhere near enough. As they found out, women in sex work had graver problems than HIV which were going unnoticed.

When Swasti led the Avahan India AIDS initiative, which was launched in 2003 by the Gates Foundation, 1,09,336 female sex workers were reached, over 600,000 new infections were averted, and HIV reversal trends were seen in all the six states where the initiative was implemented. This kind of impact was possible because of Swasti’s alternative intervention strategies which, interestingly, targeted everything unrelated to AIDS to bring down the disease.

The dicey ground situation

How does a woman find herself in this morally attacked occupation of sex work? Even if she’s not coerced by people, the sad fact is that she is coerced by dire circumstances. Swasti found that about 60–70 percent of sex workers in Bengaluru alone, work off the streets. Many, desperately in need of money, come from surrounding villages.

Being in the streets means being vulnerable to violence and harassment from the police, local gundas, and pimps. Even a woman living under a roof is not spared as she is harassed by her family, clients, and the society at large.

Most may not be aware of HIV but a greater number of these women are not aware of the laws that protect them, thereby pushing HIV further down the priority list. Prostitution is legal in India so far as it is not practiced institutionally such as in a brothel. And yet, most cases of violence go unreported, because for women, moral implications tend to be greater than legal.

A sex worker can be arrested only if she’s soliciting clients in public spaces, but this law is stretched by policemen as mass arrests of sex workers when they are simply relaxing in their public ‘homes’ is a common sight. “Once arrested, the women have to secure their release after being presented at the court, apologising and paying a fine of Rs 500,” says the report published by Swasti and Karnataka Health Promotion Trust.

Harassments like these have steadily increased their vulnerability, which is the root cause of a problem that HIV, being the celebrity manifestation, completely overshadows.

This is the reason why simply asking these women to use a condom hasn’t reduced the spread of the disease, because as Shiv Kumar, the President of Swasti, explains, “these women are not able to negotiate condom usage.”

A clear example of this is the case of Malathi, a woman now involved with Swasti. Although she knew that HIV was a risk and that a condom would help prevent it, urging the client to use one meant risking a day’s meal and was therefore, a question of survival. There have been many cases where clients, when urged to use a condom, have unleashed more violence upon these women.

How Swasti has intervened

It became clear to Swasti that to address the spread of this life-threatening disease among sex workers, they will have to first address the violence, vulnerability, and moral stigma that suffocates them.

And so came Project Pragathi, an initiative to empower women in sex work, in partnership with Swathi Mahila Sangha, a collective of women in sex work in Bengaluru. Together, they have made room for several self-help groups which now consist of fiercely independent women supporting each other.

There are ‘hubs’ in the city which, for these women, are a haven where they find physical and emotional safety. Finding any kind of aid is now simple and guaranteed as there are specific programmes for specific issues faced by them:

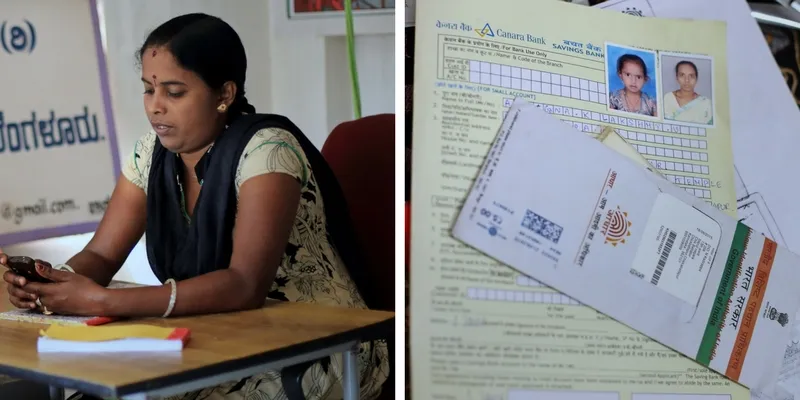

The social entitlement programme ensures that they have access to government schemes such as widow pensions, ration cards, income and caste certificates, voter IDs, etc. Their own legal aid platform called ‘Swathi Kanunu Mantapa’ educates them about their rights and has a lawyer who can support victims of violence. This along with ‘Swathi Nyaya Sanjeevani’, which is the 24X7 legal helpline, has helped several women fight cases of violence in court.

Along with a support group for HIV-positive women and for those suffering from alcohol addiction, Pragathi has also made room for a microfinance institution in the ‘Swathi Jyothi’ programme where women can manage their earnings and savings.

The impact of Pragathi cannot be missed. Each ‘hub’ or ‘Swathi mane’ sees 3,000 women walking in every month to be empowered. Women who were once terrified to walk into the police station are now fighting cases in courts. Women who couldn’t insist on condom use now refuse clients who refuse condoms simply because they are financially and emotionally more independent. Women who have faced unimaginable trauma are now Pragathi’s peer educators or ‘Jeevikas’, rightly termed as ‘life givers’ for they are on the constant lookout for other women whom they can help out of similar nightmares.

Swasti’s secret

Swasti has been diligently working in the backstage and letting their super women enjoy the deserved spotlight. But as a 15-year-old organisation that has been there, done that, their approach to this highly sensitive matter is noteworthy.

Shama Karkal, the Director of Swasti, explains that Swasti has worked to be an enabler that makes communities self-reliant. “We are a member-based organisation,” she explains. “Here it’s not the board of directors but it is the members that have a say in what needs to be done.”

“One of the first things we did was to initiate this member engagement process that helped organisations go to each member and look at their needs, what they had, what they didn’t have, and what they wanted.”

The next step, as she explains, was building a leadership capacity so that the governing members elected by communities and self-registered organisations were equipped to handle problems, either in the form of government compliance or financial management.

The most innovative of Swasti’s approach, however, has been the mobilisation of resources. “Normally, funds for an organisation come only when there’s a project proposed and dry up otherwise. We realised that this kind of dependence on funds is not necessary,” says Shama.

So, Swasti got the community thinking about creative ways to raise money. Collecting and selling newspapers, engaging in lotteries, organising cultural events and finding sponsorship for them, and even entrepreneurship where women made homemade food products to sell. The members also began raising in-kind donations for resources as basic as office supplies. In a nutshell, members acquired the know-how of raising funds and were no longer dependent on higher authorities for the in-flow.

The next non-traditional approach Swasti experimented with was doing away with member fees. “Some would pay and some wouldn’t, and trying to get this going itself was highly energy intensive,” she explains. “So we started wondering if there was a different way to look at member contribution.” Instead of bringing in money as a resource, Swasti wondered if members were willing to step out into their network, and get more people to contribute.

This approach brought them the “final piece to sustainability,” as Shama says. Swasti ensured that all the organisations were working closely with government departments and private sectors so they could remain constantly aware of the ecosystem. For instance, community members were trained by national legal service authorities so that legal help could always be available within the community.

In the end, the secret ingredient to helping the socially excluded is really this, as Shama eloquently explains,

“The fundamental thing we’re trying to change is to not look at people like beneficiaries, and as people who put their hands out and ask for help. Instead, we need to make them the agents of change.”