How would your life change if your income was taken care of? The what if’s of Universal Basic Income

What if the Government paid you a standard income every month, regardless of whether you’re unemployed or employed, and regardless of which side of the poverty line you stand on? No strings attached.

“It's going to be necessary,” Elon Musk told CNBC, November last year. The CEO of Tesla was talking about a universal basic income (UBI) that has become the hottest topic of discussion, especially with giant tech executives like Musk supporting it. It refers to a standard amount paid to every citizen be they rich or poor, and be they with or without a job.

The idea first comes across as too absurd to be practical but hold your horses because Finland, the nation which has proven time and again to be a model of social innovation, has already begun a pilot project. The government has selected at random, 2,000 unemployed citizens between the ages of 25 and 58 for a guaranteed sum of €560 a month for two years. And they will continue to receive that amount even if they find work within those two years.

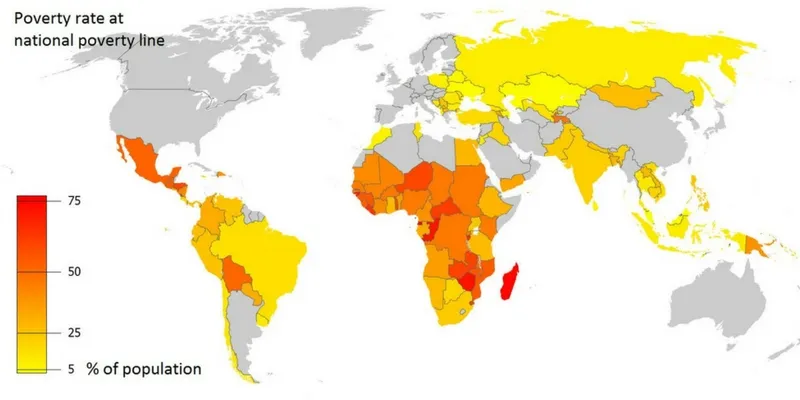

Finland isn’t the only oddball considering UBI. Netherlands, Italy, UK, Canada, and even a few countries of Africa are seriously thinking of rolling out their own pilot schemes. The Indian Government too is opening up the discussion what with the pre-budget Economic Survey 2016-17 strongly advocating UBI as a “powerful idea” to combat poverty.

All for: how it can help

How many times have we, unemployed and desperately looking for work, settled for anything that’s available? And how many times has that curbed our prospects and potential? With UBI, and through this pilot project, Finland is hoping that its citizens can enjoy a space to breathe without the worry of imminent poverty. This basic income is especially uplifting for entrepreneurs who will have greater liberty to take risks and pursue innovation.

The debate of this basic income is being fuelled, however, by the prospect and the inevitability of automation and the effect it will have on the labour force. Industrialisation is the prominent scar in history that is a reminder of the colossal number of jobs workers lost to machines. Now, the 21st century is the era of technology that is only going to advance in time. UBI has, therefore, erupted in response to the threat of humans ironically being replaced by the machines they create.

All against: how it won’t

Many believe that the end-of-job theory is not substantial enough to support the implementation of UBI. The talk of de-industrialisation 30 years ago is striking similar to this paranoia around automation, according to Declan Gaffney, an expert on social security. Experts such as him believe that ‘parking’ those who lose their jobs is not the solution, and the government must instead improve policies and regulations that support people into employment. The economy, they argue, has a way of replacing jobs that disappear.

Another worry that plagues many is that UBI will kill people’s incentive to work, and that this ‘worklessness’ and the resulting leisure will hurt the growth of the economy. It is important to note, however, that UBI in itself is not enough to pull someone out of poverty or to keep them afloat. It is only intended to provide flexibility so people have the choice of making calculated decisions in life, which is undoubtedly a luxury for the poor.

UBI is also expected by many to create unscrupulous employers that exploit workers by maintaining low payments just because they already receive a basic income. The more one digs, the more drawbacks there will be to find. The biggest catch of UBI to surpass, however, is that of increased taxes and reduced benefits for all citizens.

When Thomas Paine, an 18th-century political activist and revolutionary, proposed paying all 21-year-olds 15 pounds, it was a grant that was to be funded from tax levied on landowners. Finland’s present experiment too, draws the UBI from and replaces the unemployment benefit. The money has to come from somewhere and this flow from increased tax and lowered benefits is what will make room for UBI. The biggest hurdle, therefore, could be the larger population’s agreement and a shift in politics where leaders can overcome unpopular tax rises.

Will it work in India?

Although the Economic Survey advocated the potential of UBI, it stressed that India may not be ready for such a scheme as the current political challenges could derail it even before it builds momentum.

Jay Panda, a politician belonging to the centrist Biju Janata Dal party and one of the first lawmakers to have spoken and written about UBI in India, however, has a different opinion. As he told TheWire, India’s ‘political challenges’ is what makes it ideal for this scheme.

Currently, there are many inefficiencies in the benefit schemes India provides for its poor. For instance, in the public distribution system (PDS) about 73 percent of government expenditure for this scheme is lost on salaries and corruption. The assessment that the Planning Commission carried out on PDS revealed that out of every rupee spent by the government, only 27 paisa reaches the beneficiary.

While corrupt middlemen loot the poor of the benefits of schemes such as this, a more efficient system would be to direct these subsidies as cash directly to the beneficiaries. This would also give the marginalised the power to make decisions on how to utilise their resources rather than the government providing them with what it thinks is necessary.

An experiment conducted by Basic Income Earth Network (BIEN) in nine Indian villages found that the unconditional grants had exactly this effect on the welfare system. With a sense of control over their money, debts were significantly reduced and the empowerment of rural women was perceptible. Nutrition, sanitation, and school attendance among children were other noticeable improvements.

The obvious question

The strikingly obvious ‘flaw’ in UBI is the employed or the rich getting this basic income. It would, and does, seem to many as a waste of resource as they clearly don’t need it. A system of ‘targeting’ who needs it and who doesn’t would then seem like the better alternative.

Implementing this in India, however, may turn out to be costlier than UBI, as the government will have to invest an enormous amount of resources in conducting the research which can have holes of its own. Moreover, the basic income may not amount to much for the rich but it would be making up for the higher taxes that will have to be put in effect to make room for UBI.

For instance, when millions surrendered their LPG subsidies so the same could be given to the poor, each family gave up an annual subsidy worth Rs 5,000, saving the government over Rs 4,000 crore. A similar principle would come to play in the implementation of UBI, where the more privileged will be conceding tax benefits for the sake of those who aren’t. But in this case unlike the LPG remittance, everyone will be receiving the benefits of UBI.

There is lot more to dig out to check the feasibility of UBI not only in different counties, but also in the states within each country; especially in a country as diverse as India. Whatever its merits and demerits may be, if implemented, UBI has the potential to swing the welfare of the State, for better or for worse.