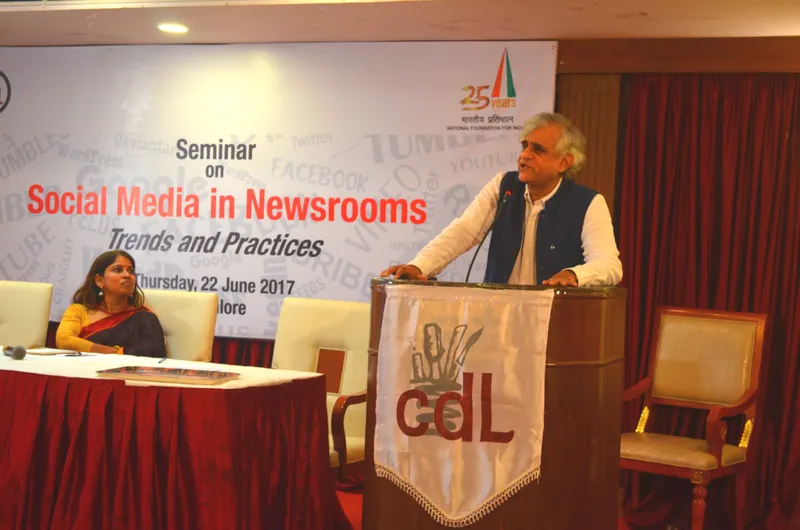

To Indian media, 75 percent of population does not matter: P. Sainath

At a time when media’s roles and responsibilities have become a hotly contested topic, veteran journalist P. Sainath says that the Indian media fails to provide news coverage of about 75 percent of the population.

The fourth pillar of Indian democracy, media, has witnessed tremendous growth and reach over the past decade. News has become an integral part of every citizen of India, where despite our interests in a particular field through social media, information about people and events are increasingly becoming more accessible to all.

However, in this melee of noise and at times overwhelming coverage of issues, the Magsaysay Awardee winner, who has covered farmer suicides and agricultural issues exhaustively over the past decades and Founder-Editor of People’s Achieve of Rural India (PARI) believes that mass media caters primarily only to the rich and the political class.

At the seminar on Social Media in Newsroom, organised by Communication for Development and Learning, Sainath discussed journalism, digital media, rural India, farmers and the much hyped and current trend of farm loan waivers.

'75 percent of population is extinct'

According to CMS Delhi, the five-year average of agriculture reporting in an Indian national daily equals to 0.61 percent, which includes politics and the agriculture ministry, while the village-level stories appear on an average of 0.17 percent. Only last year the number rose to 0.24 percent.

Sainath says that the once thriving agriculture correspondents in journalism have now being rendered extinct. Agriculture reporting centres around the Agriculture Ministry and the budget allocation given to this sector, and the reported primarily works out of Delhi. He says,

When you don't have an agriculture or a labour correspondent, you are basically saying that 75 percent of the population does not matter. The rate of unemployment in India is high. If every one were to queue in a single file, it could fill three sea shore lines in India. Forty million people do not have jobs today and the story needs to be told.

Further, there is a discrepancy in news coverage even for metro cities and Urban India where business, politics and glamour dominate the print and broadcast media. Journalism focusses only on that information that will help the organisation to make money.

Culture is suffering. In urban cities, Mumbai dominates because of Bollywood and the Dalal Street, followed by Tamil Nadu because of Chennai’s IT dominance and the large Tamil bureaucracy, which is present in every media sector. Then comes Kolkata and other 36 cities which host approximately 4.1 million Indian population. Sometimes, cities and states don't appear at all for three-four years in a row. So what ‘national news’ coverage are we talking about?

Where has the woman farmer disappeared?

With concurrent droughts, crop failure and financial disparity in the farmers income, the scale of distress among the agrarian community is vast and requires immediate attention from the government, media and the public. Although, given the large-scale farmers protest across the states, the national media have discussed the challenges faced by this sector. However, Sainath says that the myths surrounding the community remains to be addressed.

It is a national myth that India is a farmer-orientated country. But reality is that less than eight percent of the population falls under the category of a farmer.

The Indian government defines farmer as person, male or female, who cultivates a plot of land—owner or non-owner— for a period of 180 days or more. If the primary profession and source of income of an individual is farming then only does the person qualify to even be eligible for the infamous demand of loan waivers.

Further, farming has always been depicted as a male-dominated profession— from cropping, harvesting, or driving a tractor. However, 60 percent of the work in the agriculture sector is performed by women. Sainath says,

Women are excluded from the farming narrative. The Indian media always depicts a man with a plough on a barren land as a poster related to a farmer crises or rural India. But, it is the women who work on the fields— be it seeding, harvesting or even ploughing. Yet, less than eight percent of the women own any land.

Media needs to become all-inclusive

Calling media the most exclusionary profession in the Indian democracy, Sainath says Dalits and the minority community fail to get adequate positions and presentation within the media industry. Dissent, discussion and representation of every section and gender of our society forms the fabric and birth of this profession.

Elaborating on the purpose of journalism and PARI, he says,

Indian media is a child of the Indian freedom struggle. Good journalism is a society in conversation and argument with herself. Journalism needs to be an archive of the living past, a journal of the contemporary present and textbook of the future.