How an ecotourism organisation that everyone in Spiti talks about, built an unparalleled niche

Ecotourism is a high-potential startup sector today. Here is a case study of an organisation that is one of the oldest in the country, and whose growth is a unique reflection of the growth of ecotourism itself.

In 2000, 23-year-old Ishita Khanna travelled to Spiti Valley for a conference on traditional medicine. Having just completed her Master’s degree in Social Work at TISS and her thesis on tourism and its repercussions, Ishita was at the right place and at the right time.

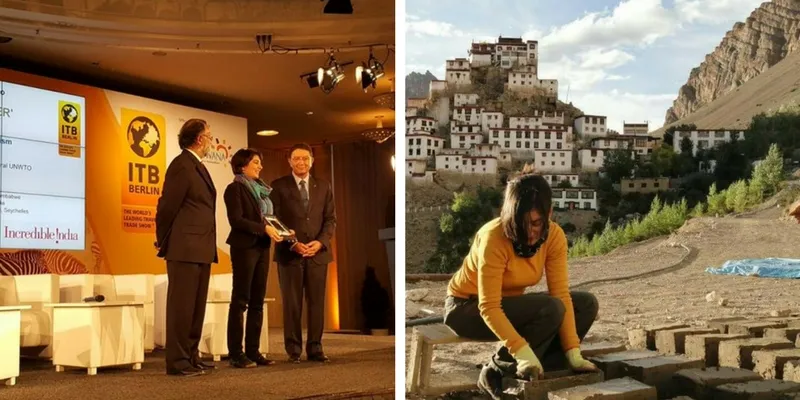

Today, Ecosphere, which is the name and face of Ishita’s pioneering initiatives in Spiti Valley, is an organisation that promotes responsible and sustainable ecotourism with an approach that simultaneously tackles economic empowerment, conservation and sustainable development.

But what begs attention is the fact that Ecosphere began its projects when even the concept of homestays, and the revenue it had the potential to generate, was alien to most. The growth of Ecosphere is, therefore, a unique reflection of the past.

Starting up

Ishita’s initiatives (through her former NGO, Muse) began with the infamous Sea buckthorn, a shrub that grows widely in the semi-arid climate of the valley. While the government of Himachal Pradesh had already begun assessing its commercial value, the project was eventually shelved and the Sea buckthorn, deemed useless.

While Ishita was trying to find a way around this, an industrialist from Delhi had already begun processing the Sea buckthorn in Ladakh to produce a juice called Leh Berry juice.

“We figured that if he can commercialise it so can we, the plant species was useful after all,” she says. And so, in 2002, Ecosphere tied up with the industrialist to process Spiti’s berries.

After working with five villages as a pilot project and marketing the idea for a few years, they soon caught the attention of the government. The processing plants have now been handed over to the locals who run all operations. What was considered a weed, and almost eradicated for it, now generates revenue under the brand Tsering.

Tapping into tourism

It was in 2004 that Ecosphere began its tourism initiatives. At that time, Himalayan Homestays in Ladakh was working on this concept in Sikkim, Spiti and Ladakh. Ishita then made the logical move of a joint programme. Until then, travellers visited through package tours organized by private organisations. Local communities, therefore, were neither participants nor beneficiaries.

Popularising the idea, however, was a challenge. Local operators such as travel agents and hotels weren’t too keen as homestays would cut into their revenue. But through word-of-mouth and media attention, Ecosphere’s services reached more people.

By this time, in 2006, Ecosphere was formed from the merger of Muse and two other local bodies. A year later, it developed its website and introduced its concepts of ecotourism to the digital world.

Not long after this, a handful other ecotourism initiatives surfaced in the country. Travel Another India and India Untravelled were founded between 2009 and 2011. They promoted sentisised travellers as opposed to unwitting tourists - a concept that has picked up momentum only in recent times.

The Ecotourism Society of India, an NGO formed at the behest of MoT, was itself formed only in 2008 to create policies and guidelines.

Preceding this, in the early 2000s many state governments had begun initiatives to strengthen ecotourism policies; but these were restricted to development of protected areas at best. In light of this, the extent to which Ecosphere promoted local involvement is commendable. “It is their land after all,” as Ishita says.

An organisation founded on experiments

Ecosphere introduced ways in which the community’s agricultural practices could adapt to changing climate; being in higher altitudes means that villages are highly dependent on winter snowmelt for irrigation.

Snowfall however varies from less than three feet to sometimes more than 15 feet and is sometimes delayed by a few months or, like in 2015, skips winter altogether. Such severe cases result in complete crop failure and communities are threatened by the necessity of evacuation.

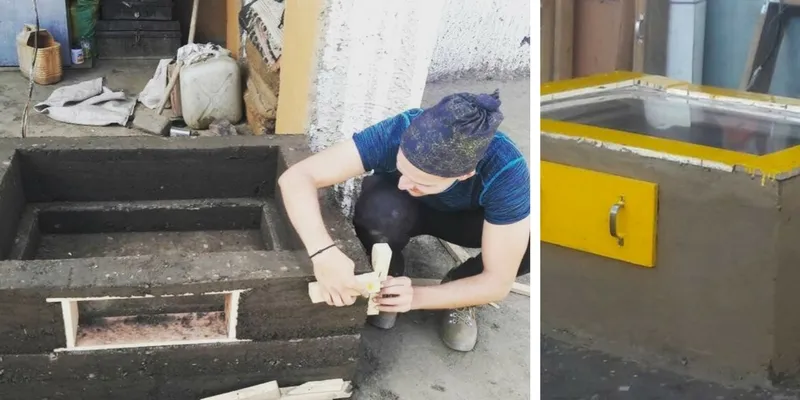

To combat this, Ecosphere introduced artificial glaciers in the region, a concept first introduced in Ladakh by rural engineer, Chewang Norphel. By training its staff and mapping the hydrogeology of the area, Ecosphere, along with villagers and volunteers, built check dams where water can be slowed down just enough to freeze, which then melts just in time for spring. It has so far built 10 check dams which have proved to be successful.

Ecosphere has also introduced greenhouses in some villages where different types of crops can be grown throughout the year, which would otherwise be impossible in Spiti’s climate.

Traditional crops include barley and black peas but without a high demand in the market, farmers are forced to grow green peas which is water intensive and therefore susceptible to crop failure. It is unfortunate, Ishita agrees, but with revenue from tourism, the locals stay afloat during drought years.

Another source of revenue for the local community which had remained untapped was traditional crafts, most of which were dying. Yak wool spinning and pottery were among them. Ecosphere worked with families that had retained traditional knowledge and trained them by strengthening traditional practices and introducing modern techniques. Travellers now spend time with local communities to learn these techniques.

“Our basic premise for all our projects has been that if you’re trying to develop a livelihood without wanting to compromise on conservation, you try to link the two up,” she adds.

What is its secret?

Ecosphere in its infant days depended on grants and donations. But with growing number of projects, it soon found it necessary to build a self-sustainable model. For this it began crafting and pricing specific travel programmes, each of which could provide a unique experience of Spiti; and the revenue generated was poured back into their projects. Today, about 75 percent of the revenue is reaped by the local communities and the rest is directed towards their conservation initiatives and newer projects and experiments.

Apart from running a cafe and a restaurant, a model that has worked in its favour is Volunteer tourism. Traditionally, a volunteer’s services is considered payment but anyone wishing to volunteer with Ecosphere is first a traveller, and therefore a consumer of Ecosphere’s services. A volunteer, however, has the benefit of subsidised rates for travel and accommodation costs.

Despite this, Ecosphere has a strong volunteer base. Almost all its new initiatives, such as bringing education into the villages and improving access to healthcare, has been driven and initiated by their reliable and enthusiastic travellers, Ishita confesses. Even the cafe is run by volunteers.

Economic self-sustainability might seem pivotal in their survival, for funding is always an essential factor, but there is another critical contributor to the evolution of the organisation.

Ishita elaborates, “What we realised was that we have to build local capacity and local leadership. All our team members except me and a girl who works part-time are completely local. In the tourism sector, if you look at any kind of hotels or restaurants, the people hired are always outsiders. The reason locals are excluded is because they have to be trained from scratch - and that we’ve done with all our staff.”

In fact, she explains with a touch of pride, the person currently managing all activities at all times is a localite by the name of Chhering Norbu.

By involving local communities, and keeping their needs at the center of all projects, Ecosphere has stayed true to the concept of Ecotourism itself. Vested interests in tourism are many considering the massive flow of revenue the country receives from it; merely ‘developing’ lands and involving private sectors for infrastructural development, as is advocated by the government time and again, does not bring eco and tourism together.

“Tourism in our country is looked upon as the number of people coming in. That for them is growth in tourism. But we should look at quality and not quantity,” she stresses.

Out of the 66 villages in Spiti, Ecosphere has covered 80 percent and has been able to introduce, some if not all its projects in all the villages. Today, Ecosphere is so well knit into the local community that almost everyone in the valley is familiar with Ishita and her organisation. How many organisations can say that for themselves?

Disclaimer : An earlier version erroneously mentioned that the artificial glaciers were introduced with the help of Chewang Norphel. The correction has been made.