Rupee is at 73 to a dollar: Here’s what matters, and what doesn’t

We all have, by now, seen posts on social media, be it Facebook, LinkedIn or even forwarded Whatsapp messages, about how our national currency, at par with the US dollar in 1947, has weakened considerably to beyond the 73 per dollar mark.

Some are linking this fall in the rupee against the US dollar to a loss of national pride, and perhaps even anxiety at a further deterioration of the rupee beyond the 100-to-a-dollar mark in the not so distant future. Indeed, the other day, I saw a post on my BITS-Pilani alumni group, which equated this parity with the US dollar to India’s days as a the “Golden Bird” and a time when everything was “cheap” – conveniently ignoring the fact that prior to the rupee’s massive devaluation in 1969, India’s per capita GDP was one-fifth to one-sixth the size of what it is today, adjusting even for the impact of inflation.

In the modern floating rate exchange regime, the currency is a national price, not a matter of national pride.

Fixation of the well-being of a society and a nation in terms of the units of national currency (Rupee, Yuan or Lira) exchanged for the global reserve currency is not exclusive to India. The bias comes from a time when each unit of currency was backed by a unit of gold (this was until the 1930s) and therefore, how much your currency was worth was often a measure of how much gold reserves you had.

In prevailing floating exchange rate regimes, though, where the price of a currency is determined by trade and investment, how much a currency is worth against the US dollar is simply a matter of calibration - a matter of National Price rather than National Pride. And a price whose strength depends on its stability, and not its level.

Let us consider this question for instance; the citizens of which of the following countries would be most inconvenienced by a depreciation of emerging market currencies? An Indonesian, in whose country, the exchange rate went from 13,000 to a dollar to 13,700? An Indian, who saw his international purchasing power erode as the rupee fell from 63 against the dollar to 73? Or a Turkish citizen with a dollar loan, when the Turkish Lira fell from 3 against the dollar to 4.5?

If you figured out the incredibly larger pain felt by the Turkish borrower as compared with those in India or Indonesia (least inconvenienced), you are on the right track. Indeed, it is not the level of the currency, but rather its rate and the pace of change that imposes financial hardship on nations.

What a currency is worth against other currencies can simply be changed through re-valuation – announcing that certain units of an old currency are equivalent to a certain new number of units of a new national currency, through a government order. In 1960, the French government simply decreed that 100 units of the Old Franc would be converted into 1 unit of the New Franc. Turkey did something similar in 2002. Neither of these measures changed the economic or financial realities on the ground. Though, of course, some French nationalists in the 1960s could have been happier as their currency had moved “closer to parity” against the US dollar.

The Indian rupee does not look as fundamentally weak as the sell-off in the past two months has suggested.

I believe this lengthy preamble was necessary in order to delineate the magnitude and nature of the real problems around the Indian rupee. The 14 percent depreciation in the rupee since the beginning of this year is perhaps the sharpest since the 19 percent drop witnessed in 2008 –raising concerns about whether we are approaching a balance of payments crisis as seen in 1991.

However, it would be better to see this depreciation in the perspective of other emerging markets with similar economic features as India (persistent current account and fiscal deficit, dependence on energy imports) and to see how they have fared over the last two episodes of emerging market currency stress – The “US Taper Tantrum” of 2013, and the US-China trade war in 2018.

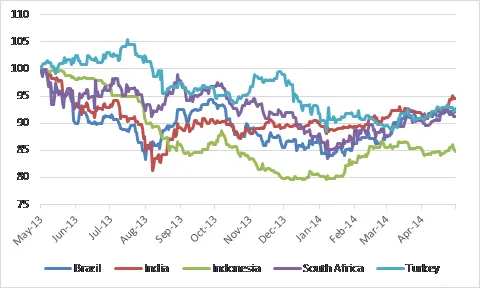

In 2013, Morgan Stanley economists coined the term Fragile Five – countries whose economies and currencies were hugely dependent on foreign capital inflows to pay for their imports and foreign liabilities. Brazil, India, Indonesia, Turkey and South Africa made up this group. The charts below show the performance of the Fragile Five currencies in the aforementioned two episodes.

Source: Bloomberg, Author’s calculations

Source: Bloomberg, Author’s calculations.

We note that the rupee has done relatively better than its peers, both in the year since the Taper Tantrum began (May 2013-April 2014), and this year until July 2018, losing about 5-7 percent of its value against the US dollar, relative to the double-digit depreciation in the other ‘fragile five’ currencies. Notwithstanding the losses over the past two months, the rupee still remains in the middle of this pack.

If we look at the fundamentals that determine currency movements, the rupee appears to be oversold, given that external balances, reserve adequacy, and dependence on foreign liabilities have significantly improved since the first episode of the currency-driven economic stress in 2013.

India has made a significant reduction to its current account balance since then, without going through a recession like Brazil. The share of Balance of Payments that needs to be funded by foreign portfolio flows (Basic Balance) has dramatically shrunk from 3.1 percent of the GDP to 0.7 percent due to robust FDI flows, and a minor but significantly rising share of this has been to startups.

The build-up in forex reserves in India has been the strongest among the eight major emerging markets (China, India, Brazil, Russia, Indonesia, South Africa, Mexico and Turkey) and it is among the only two in the group that have seen their external debt (relative to GDP) decline steadily.

Excessive reliance on similar risk models has exacerbated sell-off episodes across asset classes.

Given these realities, it is indeed puzzling to see such a sharp depreciation in the rupee against the dollar. In my understanding, the apparent irrationality of the markets rests on four factors.

The first has much to do with the biggest risk in investing in any asset class in modern times – volatility. Eric Lonergan, the famous macro hedge fund manager, mentioned this in his brilliant article on how investor behaviour globally is becoming more and more correlated – this can push up prices well on either side of the fundamentals.

Witness how the Cyrpto Bubble spectacularly rose and fell, or how, for no apparent reason, did the global equity markets suffer a flash crash in the first week of February. One of the features of modern investing is we have abundant data which can be sufficiently dissected to build Value at Risk (VAR) and volatility hedging models that can anticipate and trade daily price movements. This makes eminent sense for brokerages and investment banks who trade in securities and derivatives, and have to maintain daily mark-to-market requirements, not to say, also build a profit book to remain in business.

The problem begins when the specific needs of high-frequency traders are adopted by investment managers with longer-term time horizons – mutual funds and institutional investors in emerging markets such as India – in the name of embracing technology and innovation. Given their large holdings of emerging market securities, both in stocks and bonds, their response to any short-term change in global risk sentiment can often trigger volatility, and sell-offs that are not in line with fundamentals.

This has manifested itself in situations where any sell-off is magnified because there are not enough buyers for each seller, and perhaps both are using the same models to price risks to their portfolio investments, despite the difference in their investment objectives and investment horizons.

Though the reason for the sell-off in the rupee cited above is not proven by any rigorous research so far, the prevailing episodes of high volatility in emerging market assets, and the fact that prices can remain misaligned from fundamentals for long periods, present prima facie evidence to investigate if the sell-off in the rupee, to some extent, comes from a market microstructure problem.

The rupee’s movements may simply be showing a reversion towards the general bearish trend in other emerging market assets.

The second reason behind the sell-off in the rupee against the dollar is related to the first. If we assume that during periods of high-risk, such as now, investment managers in emerging markets do not concern themselves with the fundamentals of a particular market, but rather sell and buy these assets in the aggregate.

In such a scenario, the degree of correlation between Indian markets and other emerging markets increases. When we examine the Indian equity market (in US dollar terms), against the MSCI Emerging Market Index, this indeed seems to be the case. Until July this year, the Nifty had been outperforming the MSCI EM Index by 3.5 to 4 percent over a two-year period. Moreover, the Nifty’s outperformance was consistent since mid-2014.

So strong was the global investor confidence in India’s prospects that money continued to flow into the equity market even when the overall confidence in emerging market equities was down. In fact, Q2-2015, Q1-2016 and Q1 and Q2 2018 saw Indian equities rising even when emerging market equities fell, or massively lagged behind. However, given that most foreign asset allocation into emerging markets takes place as an aggregate and not in terms of flows to a specific country, periods of negative correlation between asset prices in emerging markets and India are likely to be short-lived – primarily because individual portfolio managers are unlikely to take a large single-country specific exposure.

If this conjecture is true, then what we have witnessed since July is simply a renormalisation of the longer trend of co-movement of Indian equity markets with emerging market equities where both have been unfortunately hammered due to capital outflows. What is true of publicly-listed equities is also likely to be true of bonds, corporate credit, and other over-the-counter instruments where investors are likely recalibrating their exposure to India by selling the rupee.

The flipside to this scenario is that when global investor appetite to emerging markets returns, we are likely to see an equally sharp swing in the favour of Indian assets.

Source: Bloomberg, Author’s calculations

Chart 4: For small periods since 2014, Indian markets have moved independently of other emerging markets, that seems to be changing since July this year Source: Bloomberg, CEIC EuromonitorWhile the first two reasons are what economists would call externalities – things beyond the control of our policymakers – the next two aren’t.

In an environment of rising crude oil prices and stubborn fiscal deficits, foreign investors might need further credibility from the government and the Reserve Bank of India towards their inflation targets.

Theories on relative purchasing power parity tell us that in the short-run, exchange rate movements between two countries should be closely related to the difference in inflation. This has also been the case between India and the US. As the chart below shows, rupee depreciation since 2012 (for which the latest CPI series data is available) has consistently moved in line with the difference in inflation between the US and India. However, that pattern seems to have been puzzlingly broken since May, with the rupee depreciating sharply despite the difference in US and Indian inflation having narrowed to less than a percentage point.

To me, one explanation of this anomaly could be the expectation among Indian foreign exchange market participants – investors, traders, companies and market makers – that though inflation in India is low right now, it might shoot up significantly in the near future, not least around the period when they wish to lock in their exchange rate risk. The reasons behind this worry could be two-fold. First, the Indian economy, like those of the other Fragile Five, remains critically dependent on crude oil imports (80 percent of total demand), whose prices are marked in US dollar and immediately weigh down the balance sheets of traders who import crude oil.

Presently, crude oil is traded close to $80 per barrel, up 38.6 percent from last year. Therefore, despite lower inflation today, and recent cuts in fuel taxes by central and state governments, there is a risk that eventually, downstream energy companies will capitulate to rising energy prices abroad, and raise prices at home.

Also related to these are concerns about the RBI’s ability to maintain its inflation target of 2-6 percent, which it had committed to in August 2016. The RBI has remained committed to stabilising inflation expectations since 2013, under Governors Raghuram Rajan and Urjit Patel. In a study that this author undertook at his previous job two years ago, it was found that about 35 percent of the slowdown in inflation (1.2 pp) between 2013 and 2016 came from lower and stable future inflation expectations over the period - similar in magnitude to the downward impact on inflation from lower crude oil prices.

That said, India’s inflation targeting framework was formulated at a time when crude oil prices were low and capital inflows to emerging markets were favourable. In that regard, the current sell-off in the rupee may simply reflect investors’ scepticism about the commitment of India’s central bankers to keep inflation within the targeted range.

To an extent, that scepticism is valid - almost all emerging markets (even China!) have an inflation targeting framework, and yet, very often they fail to bring inflation down to those specified targets.

A case in point could be Brazil, where political considerations have limited the central bank from anchoring inflation expectations between 2014-16, or Turkey and South Africa, where the patronage from politicians has meant that the central banks have been regularly shielded from accountability, despite having persistently overshot their inflation targets.

The RBI’s response to its inflation target has been credible, even in the face of the sharp depreciation in the rupee over the past two months. If it is able to convince the markets that it is unwilling to intervene in the FX market by selling dollars to shore up the rupee, and will only increase interest rates when the impact of depreciation begins to pass through into inflation, it may be able to durably bring back the confidence that seems to have been lost in the rupee.

That said, the credibility of the government to stabilise inflation expectations matters too. Any increase in rupee balances increases its supply, and hence decreases the price (exchange rate). While the current Union Government did a commendable job in complementing the RBI by pursuing a prudent fiscal policy and desisting from giving unproductive and inflationary agricultural sops in the first half of its tenure, the temptation to be fiscally extravagant seems to be getting stronger as we move towards the general elections in 2019.

Furthermore, a key reason why the government’s credibility for fiscal prudence has been adversely affected has been due to its inability to curtail spending at the state level. Unlike every other metric relevant for the rupee on which India has improved over the past five years, fiscal deficit has remained stubbornly unchanged at 7 percent of the GDP (adding central and state deficit).

Show your commitment to reining in inflation and deficits, and they will come back.

As the rupee looks poised to cross the 75 against the dollar mark, policymakers and investors need to carefully consider the things they can control, and those they can’t. If we are committed to the ideals of economic liberalism that were adopted by political leaders in 1991, then imposing capital controls to prevent foreign investors from selling Indian assets, and trying to influence market microstructure unilaterally is not a solution. Nor is commentary to verbally talk up the rupee, like US President Donald Trump attempted to do in the case of the dollar, a solution in the long-run. What the government and the RBI can credibly do is to increase the confidence of the markets in their inflation and fiscal deficit targets.

A good example of what institutions can do right at times of uncertainty around a country’s economic future comes from the UK. Despite the political ineptness and confusion around the relationship of Britain with the EU post Brexit, the Bank of England has remained steadfast in its commitment to keep domestic inflation around target of 2 percent, backing it up with its monetary policy actions (specifically, resisting the temptation for a prolonged quantitative easing) over the past two years, ever since the June Brexit referendum sent the pound sterling plunging.

Consequently, the sterling has remained stable around the 1.3-1.4 range against the dollar, defying market expectations to drop down to 1.1 levels against the dollar as the Brexit deadline of March 2019 approaches. And though the prospects of the UK economy and the sterling post Brexit do not look appealing, the actions of BoE in the interregnum will be remembered as the core reason why the Brexit-related pain did not come to the UK economy as early as was expected.