A company can only be as big as its market, says Ashmeet Sidana of Engineering Capital

In this week’s 100x Entrepreneur Podcast, Ashmeet Sidana, Founder of Engineering Capital, talks about why entrepreneurs should zero in on a very narrow problem with broad application, and how to estimate the right market size.

Ashmeet Sidana, Founder and Managing Partner of Engineering Capital | Image Source: 100x Entrepreneur Podcast team

Entrepreneur and venture capitalist Ashmeet Sidana is the Founder and Managing Partner of Engineering Capital, a VC firm that focuses on and invests in tech startups.

Born to a farmer father, Ashmeet spent his childhood in a mud hut and considers himself lucky to have later moved to Delhi for his education. From there, he ended up in the US “because I always wanted to be an engineer”. His love for computers led him to Stanford University where he studied computer science. Since then, he has lived and worked in Silicon Valley.

Ashmeet started his career at Hewlett Packard as a R&D Engineer in 1989. An alumnus of The Wharton School, Ashmeet took the entrepreneurial plunge in 1995, when he founded Sidana Systems. Sidana was later sold to Doclinx in 1999, after which Ashmeet started his stint as a VC at Foundation Capital in 2004. He eventually founded US-based Engineering Capital.

Engineering Capital usually invests in the seed stage of companies, often becoming the first external investor of tech startups. The VC firm has invested in companies including Robust Intelligence, Concentrix, and vFunction, among others.

In a recent episode of 100x Entrepreneur Podcast, a series featuring founders, venture capitalists, and angel investors, Ashmeet shared with Siddharth Ahluwalia his investment thesis and the approaches he follows to evaluate tech startups that he invests in.

Engineer-focused fund

Ashmeet founded Engineering Capital in 2015. “I noticed that even in Silicon Valley, most of the venture capital was focused on market or consumer insights. We had drifted away from our original roots, which of course was Silicon Valley. It was a deeply technical area,” Ashmeet says.

At Engineering Capital, he focuses on early-stage investments in companies that have technical insight. Ashmeet goes on to say that while technical insight is a necessary condition, it is not sufficient. “In VC, we are trying to build large businesses. And to build a business, you have to solve many other problems,” he says.

Having said that, Ashmeet believes that starting with a technical insight gives an entrepreneur an advantage in building a large business. “Some of the best Silicon Valley companies have started with technical insight,” he says.

Differentiating between technical, market, and consumer insights, Ashmeet cites examples: Google was a company started with technical insight, Facebook with consumer insight, and Amazon with market insight.

“You can start companies with any one of these. They are different journeys. The trade-offs are different, and they all work in venture capital,” he says.

Investment thesis

Ashmeet reveals that he invests in less than one percent of the companies that he meets. “That does not necessarily mean that they are not good business; it just means that they are not a match for what I am trying to achieve,” he says.

He says most technical insights are not good venture-backed opportunities. Thus, it is important to understand that technical insight is necessary but not a sufficient condition to build an amazing technology company.

Ashmeet says many insights get rejected when they do not have practical use, application, or do not solve a current problem. Great technical insight may also be rejected despite having use if it requires too much capital. “It is not conducive to the venture model,” he adds.

Engineering Capital invests in companies that have technical insight and are solving an urgent problem, for which customers are willing to pay.

He adds that VC is a very extreme form of investing and resides on the very edge of the risk-reward curve.

According to him, a great founder is someone who is disproportionately ambitious and willing to take risks. “A person who has the technical savvy, but also the business savvy to build a real business around it,” he explains.

Approaching a business

The natural instinct of entrepreneurs is to go after a big problem and try to solve that. However, Ashmeet believes that this isn’t the best approach. He says entrepreneurs should identify an incredibly narrow problem that has broad application.

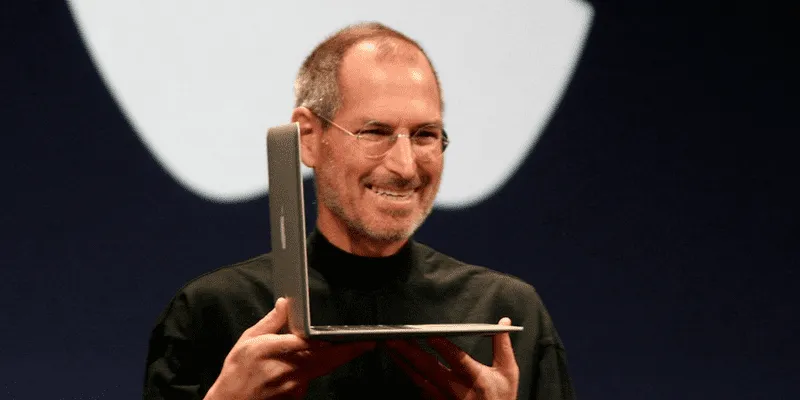

The perfect example of narrowing down problems with broader applications is the iPhone. Ashmeet says that during the launch of the first iPhone, Steve Jobs focused on three solutions that the smartphone could provide: it could allow its users to make phone calls, access the internet, and play music.

Steve Jobs

“He had successfully narrowed down the problem...and built the world’s largest company on the back of that,” Ashmeet says.

He adds: “I advise entrepreneurs to be careful - the risk factor for them is not starvation, it is gluttony...aim for less and you are more likely to be successful.”

Getting the market size right

Apart from being an entrepreneur and an investor, Ashmeet has also taken classes at Stanford University, University of Southern California, Wharton, and others. He takes a class called ‘Market Size’ from a VC perspective, which can be described as “market size for markets that don’t exist yet.”

Ashmeet says, “One of my frustrations is that often entrepreneurs don’t think about the market that they’re going after well. So, I developed this class as a way of giving back by talking to people.”

In his class, Ashmeet explains how an entrepreneur or a VC should think about a new market. In other words, how one should estimate the size of a market that does not exist yet. He explains that companies that fail are not because entrepreneurs don’t work hard enough, lack good insight, or don’t get financed. Companies fail when entrepreneurs estimate the market size incorrectly.

“A company can only be as big as its market,” Ashmeet says. And thus, it is extremely important to get the market size right.

After selling his first company Sidana Systems in 1999, Ashmeet took a couple of years off to spend some time in Nepal. “It was a life-changing experience,” he recalls.

The entrepreneur-turned-investor says building a company is very much like climbing a mountain - no matter how daunting the climb, one can only take one step at any given point of time.

“Whether you are starting a company or want to achieve a goal, just go and take the first step. Then take another one, and then another. Pretty soon you will know that you can make it happen, and even climb a mountain,” Ashmeet says.

(Edited by Teja Lele Desai)