AI will do the ‘dirty, dull, difficult and dangerous’ work, and give us more time to be human – AI expert Toby Walsh

The author of ‘2062: The World that AI Made’ shares insights on upskilling in a world of AI, the need for regulation, and the future of work.

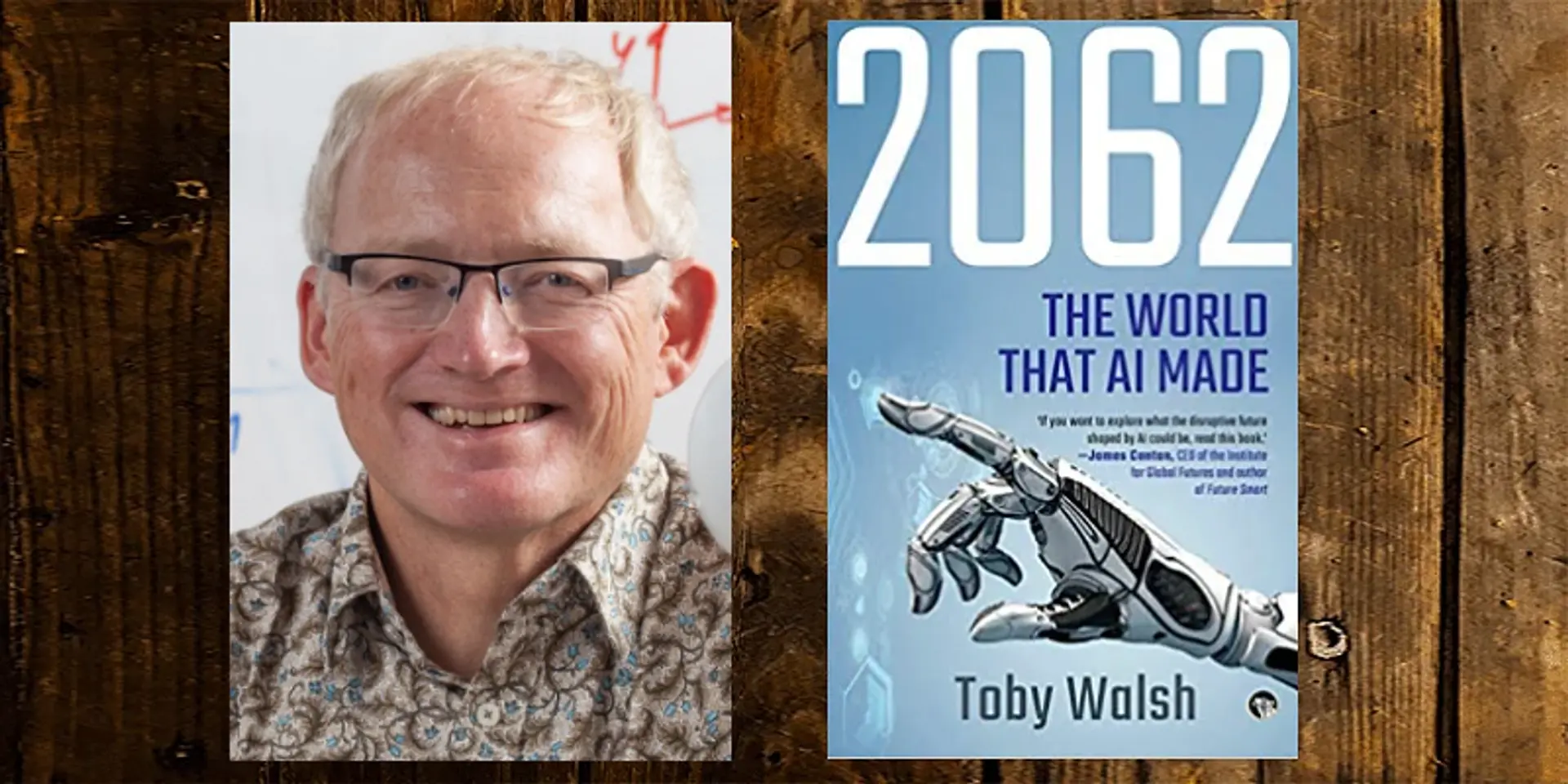

Toby Walsh is the author of 2062: The World that AI Made. It shows how the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) poses serious philosophical, economic and social questions for all of us. AI is making a serious impact in sectors ranging from healthcare and education to manufacturing and politics (see my book review here).

Toby Walsh is an AI professor at the University of New South Wales, and a Fellow of the Australia Academy of Science, and of the Association for the Advancement of AI. In 2015, he was one of the people behind an open letter calling for a ban on autonomous weapons or killer robots.

See also YourStory’s Book Review section with reviews of over 280 titles on creativity, entrepreneurship, innovation, social enterprise, and digital transformation.

As part of the Tata Literature Live Festival 2020, YourStory had a chat with Toby Walsh on AI and ethics, the scope of regulation, and future trends in AI (see video here).

Edited excerpts from the interview:

YourStory [YS]: India is known as an IT services hub and now has the world’s largest number of startups. As they create AI-based products and services, how should companies go about building ethical principles into AI?

Toby Walsh [TW]: This is an important issue to address. Ten years ago, we didn’t have to worry about questions of AI accountability. But in the last half-dozen years or so, AI is infiltrating our lives more and having consequences. It is even being used to manipulate elections and change presidents.

So organisations should think about the use, misuse and abuse of AI. They should think about the unintended side-effects of AI. Leadership at the top should set out their ethical principles and show moral leadership

For example, in the case of Google and Apple, people feel they are getting a fair return, and that their products are useful and respect privacy. In the case of Facebook, we are starting to realise that we are the product, and we are getting very little in value in return.

Customers should see that they are getting value and a balanced return. Companies should not just suck up data and use it for nefarious purposes. They should earn the respect of their customers.

YS: In a world of increasing polarisation, fake news and hate speech, how can AI help inject more balance instead of becoming weapons of mass persuasion?

TW: We have seen the rise of digital tools in political campaigns during Barack Obama’s election. Later, social media and AI drove divisions and polarisation.

This will require legislation, because these are very powerful tools. There are rules that regulate uses of traditional media for political purposes, including the amount of money that can be spent on campaigns.

We want people to win elections based on the popularity of ideas, not on the strength of the pocket and abuse of data. We don’t want people with the most money to win elections, or media barons. Elections should be a result of the democratic will of the people.

Television is persuasive, and social media can be much more persuasive and are cheaper. Fortunately, we are seeing some social media companies behaving in a responsible way. For example, Twitter has said it will be getting out of micro-targeting, which is to be applauded. But Facebook has not, so we need to regulate this space. Political conversations should not be manipulated and distorted.

The only way to respect democracy – and I am pleased to be speaking in the world’s largest democracy – is to regulate social media. During the Arab Spring, we saw how the democratic voice of people helped overthrow corrupt rulers.

YS: What can be done to ban weaponisation of AI, which you refer to in your book as killer robots and Lethal Autonomous Weapons (LAW)?

TW: I became an accidental activist in this space, and have spoken on this issue at the United Nations half a dozen times. There are thousands of my colleagues involved in this movement. Such kinds of weapons will take the world to a dangerous place, with more destabilisation and terrorism.

Machines are not moral beings, but their use in war will change the character and speed of war. They should be banned as weapons, like nuclear and chemical weapons. More than 30 countries have called for a pre-emptive ban. I encourage citizens of India to join this debate and take up action. We don’t have to move towards a Terminator-like world.

YS: This year 2020 will be known as the year of the COVID-19 pandemic. How has AI helped in humanity’s fight against the pandemic, and what were some of its limitations?

TW: In the early stages, since this was a new experience, there was not data on how to interpret or treat it. But now, AI algorithms have helped analyse COVID scars from lung X-rays, devise new therapies for at-risk patients, and helped scientists invent vaccines. We will have lots of tools in place when the next pandemic occurs.

More broadly, the pandemic has spurred discussions on relief measures and Universal Basic Income. AI should help rebuild the world, which needs a more caring form of capitalism. We can reinvent the world as a more caring and inclusive place, without the earlier inequalities. All of us should benefit from technologies like AI, and not just the wealthy.

YS: Issues of ethics in technology use and business practices have been around for a while – what is new about ethics in the context of AI?

TW: Many questions on issues of ethics are old, but what is new is we have programmed computers to make important decisions, whether it is in autonomous vehicles or weapons. Therefore, I believe we are entering a Golden Age of Philosophy.

We have to be very precise in the instructions we program into our computers, accounting for all scenarios and behaviours. Every company is going to need a Chief Philosophical Officer, to help with the precision in decisions.

YS: Here’s a good question from the audience. One aspect of ensuring fair use of AI is in the algorithms, but what about removal of bias and prejudice in the data that is used to train AI?

TW: Machine learning algorithms learn from the historical data that we give it. But there is a risk that this can perpetuate biases of age, gender, race, religion, caste, and so on.

At the same time, we should acknowledge that there is some amount of bias everywhere, and there is no unbiased answer. We should reduce bias but also ask how happy we are with the level of bias that may remain.

YS: What kinds of threats will AI pose to jobs, and how can we reskill ourselves in the face of this challenge?

TW: Technology has generally created more jobs than it destroys, but we have to ensure that this is not reversed. The pandemic has accelerated technology adoption.

There are three kinds of upskilling we can do. One is to acquire technical skills, but not everyone can do this. The second is to increase skills that require emotional and social intelligence. This includes people-facing jobs such as sales persons, doctors, and psychologists.

The third category is artistic and artisanal skills. We will value things that are made by human hands.

YS: When do you think we will see, in a future literature festival, a robot reading a poem or an AI programme presenting a novel or play?

TW: We may see a computer presenting a bad novel or some not-so-great poetry. But we are not going to have a machine as a Shakespeare. Machines are uniquely disadvantaged because only humans do human things like falling in love. Literature is based on our shared human experiences, aspirations, and sense of loss or achievement.

It binds us together as humans. What AI does is to give us more time, and we will have time to be more human.

YS: Here’s another good audience question. What can AI teach us humans?

TW: AI will help us understand how to be better humans. They will make us appreciate more our human values and relationships.

The most valuable gift that machines can give us is our time. We can spend more time with our families and communities, and that is a wonderful gift.

I always like to joke that the only obscene four-letter word is ‘work.’ If machines do more of our work, it gives us more time.

Technology has given us more time over the years, for example the weekend is a product of the industrial revolution. As long as AI does the work that is ‘dirty, dull, difficult and dangerous,’ the better it is for us humans.

YS: What can be done to make the Big Tech firms more accountable? How can we make the people’s voice be heard?

TW: People do have a voice. The can vote at the ballot box, and they can vote with their pockets and wallets. They can walk away from Big Tech firms if they find their behaviour unacceptable. I logged out of Facebook a couple of years ago.

YS: Looking ahead, what are some exciting things you see that AI can do next year and beyond?

TW: In healthcare and education, AI can help bring the best knowledge to apps in smartphones, and democratise access in remote and underserved communities. Many deaths are happening due to causes that can be fixed.

Education is the greatest social leveler, and access to education via digital tools can help people lift themselves up. AI offers so much promise.

YS: As we wrap up the year 2020, what is your overall mood about AI?

TW: I am optimistic about AI in the long term, but pessimistic in the short term. AI can help tackle the challenges of climate emergency and social inequalities.

I am optimistic that by 2062, AI will have made the world a better place!

Edited by Anju Narayanan