An eye on better AI: what important steps we must take today for a brighter digital future

This provocative book by artificial intelligence expert Toby Walsh spells out emerging social, business and policy challenges of the digital world.

Launched in 2012, YourStory's Book Review section features over 275 titles on creativity, innovation, knowledge work, and digital transformation. See also our related columns The Turning Point, Techie Tuesdays, and Storybites.

Though artificial intelligence (AI) may not surpass human intelligence for at least a few more decades, it opens up opportunities and challenges that we must address today in order to shape a better world for us all.

A call to action for business leaders, entrepreneurs, academics, and policymakers is effectively made in Toby Walsh’s new book, 2062: The World that AI Made. The rise of AI poses serious philosophical, economic and social questions for all of us, and more vision and collaboration are urgently called for.

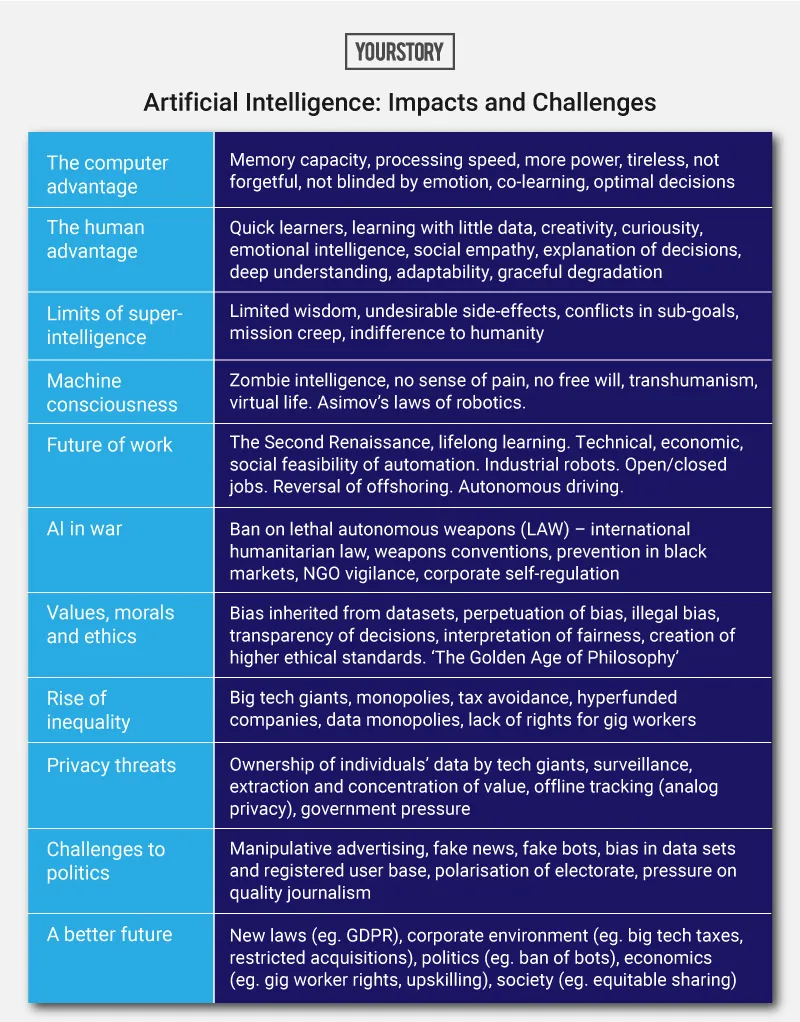

How many jobs will AI take away or create? How is AI going to affect politics and war? How is AI forcing us to redefine what really makes us human? How will AI eventually create more prosperity and happiness in society? These are some of the questions discussed in the 11 chapters in the book.

Toby Walsh is an AI professor at the University of New South Wales, and a Fellow of the Australia Academy of Science and the Association for the Advancement of AI. In 2015, he was one of the people behind an open letter calling for a ban on autonomous weapons or killer robots.

Toby is also a speaker at the Tata Literature Live Festival, being held online this week. YourStory is the moderator of this session (see here for more details).

A survey conducted by the author in 2017 on 300 leading experts indicates that half of them expect that by 2062, we will have built machines as intelligent as humans.

The book has a wide scope and quick pace, and is thoroughly referenced with around 20 pages of notes and sources. The mood swings equally between hope and worry, between speculation and concrete examples.

“The golden age of philosophy is just about to begin,” Toby writes. There could even be a Second Renaissance, with more flourishing of art and creative enterprise. But this future is something we need to actively participate in, starting right now.

Here are my key clusters of takeaways from this thought-provoking 300-page book, summarised as well in the table below. See also my reviews of the related books, Innovation Ultimatum, Prediction Machines; Seeing Digital; A Human's Guide to Machine Intelligence; Machine, Platform, Crowd; and The AI Advantage.

Foundations

The successor of homo sapiens is homo digitalis, Toby evocatively explains. We will live simultaneously in physical, virtual and artificial worlds. AI is the “most powerful magic ever invented”, he writes.

Spoken and written language, spurred by print and digital media, sparked a revolution in collective knowledge over the millennia. Thanks to software code and cloud platforms, computers can “co-learn” on a planetary scale.

“Co-learning is one reason why homo sapiens don’t stand a chance against homo digitalis,” Toby emphasises. “Unlike our memories, code doesn’t decay,” he adds. Thanks to machine learning, computers can also learn to do new things from their experiences.

The analog world can be “slow, messy and dangerous,” and we have the power to create a “fair, just and beautiful” digital future. “We are at a critical juncture,” Toby observes, where we can decide what kind of ethics we want to program into AI and how to do it for an equitable world.

Though AI achievements like DeepMind’s victories in the Go game were high profile, the fact is that AlphaGo won only because it could play against itself billions of times and use Google’s vast server farms, Toby explains.

AI is actually not yet good at learning from little data, which humans are better at. AI has performed well in narrowly-defined tasks and domains like radiology, trading, and legal contracts – but artificial general intelligence (AGI) for all tasks is much tougher.

Still, it will be possible to outsource many tasks to AI in the future, and leave us to focus more on the human experience and play to our strengths. We will augment our biological form with digital assistants and digital avatars, Toby writes.

Just as planes fly in a manner different from the flapping wings of birds, so also AI can open up new avenues of intelligence different from the human form. Cephalopods like the octopus also have different forms of intelligence, almost as if each leg has its own brain, Toby describes.

“Even without free will, we will want intelligent machines to behave ethically,” he emphasises. Challenges arise since even humans don’t always behave ethically and don’t agree on some ethical standards, as seen in the classic ‘trolley problem.’

The future of work

As AI takes over many of our tasks, we will have more leisure in future. “It might be called the Second Renaissance,” Toby poetically describes, with more arts, artisanship, community engagement, and progressive debates.

Comparing the 1900-1960 period to 2000-2060, he feels there could be more of an increase in the duration of weekends, and more scientific impact on our lives. Though AI will automate many physical and cognitive tasks, it is unlikely that it will displace jobs like bicycle repair person, since it is a complex task and may not be economically viable to automate.

“The history of technology has been that more jobs are created than destroyed by new technologies,” Toby observes. Some types of jobs will be only partially automated. Industrial robots, however, have reduced jobs and wages as well.

The author distinguishes between closed jobs (eg. window cleaning, with a fixed amount of work and windows), and open jobs (which expand as they are automated, eg. chemistry, law).

Though an ageing society will open up jobs in the eldercare sector, there may be increased preference for human support rather than robot assistants, Toby writes. Reversal of the offshoring of jobs to developing countries, thanks to AI and robotics, may adversely affect their fortunes, he cautions.

As second-order effects, autonomous vehicles could redefine urban work and life in a way similar to how automobiles reshaped cities and lifestyles.

“Learning will need to be lifelong,” Toby cautions, as humans need to keep reinventing themselves. “AI is likely both the problem and the cure,” he observes, pointing to AI-based personalised learning tools to develop new skills after AI has displaced some jobs.

“The most important human traits in 2062 will be our social and emotional intelligence, as well as our artistic and artisan skills,” Toby predicts.

Politics and war

A worrying development is “War 4.0” or the use of lethal autonomous weapons (LAW) that can destroy human life and don’t need to be fed, paid or rested. “If history has taught us one thing, the promise of clean war is and will likely remain an illusion,” Toby warns.

Autonomous weapons further disengage us from the act of war and its moral considerations. “As with every other weapon of mass destruction – chemical weapons, biological weapons and nuclear weapons – we will need to ban autonomous weapons,” Toby advocates.

These weapons of terror have also become “weapons of error” as seen in the number of unintended targets in drone attacks. Unfortunately, humans haven’t yet figured out how to build “ethical robots” either. Government, industry and academia, therefore, need to cooperate to ban killer robots.

“Whatever happens, by 2062 it must be seen as morally unacceptable for machines to decide who lives and who dies,” Toby urges.

In politics, social media and AI have played a positive as well as a polarising role, as seen in the case of Facebook and Cambridge Analytica. Many social media firms have not done as much as they could and should have to reduce political distortions, manipulations, fake news, and hate speech.

Sophisticated digital tools will only increase the number and impact of fake videos and fake accounts. The news media has also suffered adversely due to loss of income and readers to tech giants, Toby laments. He calls for laws to limit the use of algorithms in elections and tech giants in political lobbying.

Human values

One intriguing chapter explores the complexity of what fairness actually means, and how it can be programmed into AI. Machines can be more precise and act faster in many cases, and we should be holding machines to higher ethical standards than humans, Toby argues.

Though humans are known for acts of kindness and support for the underdog, there are also unfortunate tendencies towards bias and prejudice. There is a risk that current biases in data may also be passed on to AI, eg. gender skews in statistics about professions.

Toby calls on tech giants to take responsibility for their algorithms and data, and fix problems of bias in factors like race and gender. Even though they offer “free” services to the public, tech firms have a duty not to perpetuate prejudice.

Though some AI programmes in the law enforcement sector may not specify race as a data attribute, postcodes can be a proxy for race in the US and UK. Toby calls for transparency and oversight in such cases. The Algorithmic Justice League is an initiative to challenge biases in decision-making software.

A lot needs to be done in the area of corporate ethics, where big tech firms conduct social studies without the ethical rigour practised by academic institutes. Children’s rights and privacy in the online world should also be protected more rigorously, Toby argues.

“The next few decades could be a boom time for philosophy,” he observes. “By 2062, every large company will need a CPO – a Chief Philosophy Officer – who will help the company decide how its AI systems act,” he adds.

The field of “computational ethics” will flourish. The ultimate goal is to make homo digitalis more ethical than homo sapiens.

Socio-economic equality

Education has helped reduce poverty levels around the world, but social inequality is rising, particularly in OECD countries like the US. Trickle-down economics is not working as predicted; in fact, when the poor get richer, the rich do also, Toby observes.

Today, the big tech giants dominate their digital markets. Fair market practices can be ensured by breaking up large monopolies, as seen in the case of Big Oil, Big Tobacco and Big Telecom (Standard Oil, American Tobacco Company, AT&T). But the European Commission seems to have more success than the US in dealing with anti-competitive behaviour in the tech sector, Toby shows.

A lot of research that has been commercialised by the tech giants has actually been government-funded, eg. DARPA, CERN. Yet, large corporations aggressively try to avoid paying taxes, Toby laments.

Fortunately, some countries like Germany are giving workers more say and share in companies. Large monopolies should be broken up, and gig workers should be given better health and family benefits, the author argues.

Other possibilities discussed are universal basic income and a higher minimum wage. Such moves call for vision and boldness.

Privacy

“If data is the new oil, machine learning is the refinery of these large datasets,” Toby describes. But unlike oil, data generates more data and can be reused and replicated without limit.

Unfortunately, data gathered by tech firms puts an individual’s privacy at risk, and the revenues generated from this data accrue to the tech firms and not the individual owners of the data.

Some tech firms like Apple stand up for privacy in countries like the US but not in others like China, the author shows.

Many smart city initiatives also involve considerable citizen surveillance. “Analog privacy” is at risk, thanks to IoT wearables and ubiquitous CCTV cameras, many of which operate without adequate privacy legislation, Toby cautions.

He calls for more laws for data protection and privacy, and provisions for individuals to opt-out and delete their data. Interestingly, AI itself can help here in the form of privacy and security assistants on smartphones.

The road ahead

The concluding chapters discuss developments like the rise of China’s ambitious AI agenda on the policy, industry and academic fronts. The size of the domestic market itself offers huge potential for AI, though there are concerns over surveillance and ethics.

The national AI plans of the US, UK, Canada, India and France are also briefly mentioned. More investment into AI but also progressive regulation are needed, Toby emphasises. For example, new economic measures will be needed to give rights to gig workers.

Platforms must be held liable for their content, including fake news. Big tech firms should not be allowed to buy up other companies who compete in some features, eg. Facebook’s acquisition of WhatsApp and Instagram.

“If we make the right choices, AI promises to make life better – not just for the few, but for the many. It can let us all live healthier, wealthier and perhaps even happier lives,” Toby signs off.

Edited by Kanishk Singh

![[TechSparks 2020] How AI-enabled customer service is becoming more humane](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/25e9e0e0605211e984534d4121ad4bb6/Screenshot20201112-125008-1605166125873.jpg?fm=png&auto=format&h=100&w=100&crop=entropy&fit=crop)