The fourth dimension of design thinking

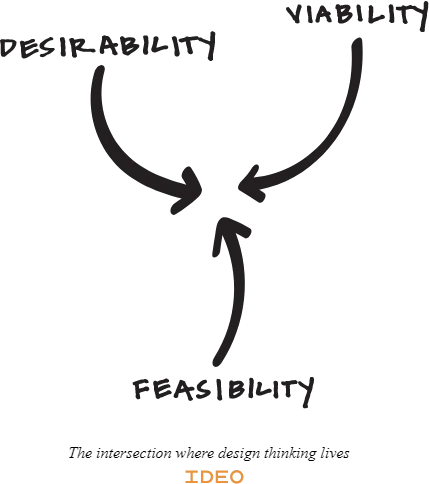

One of the unique and pragmatic aspects of design thinking is its simultaneous focus on human desirability, technical feasibility, and business viability.

Design thinking is a human-centric systematic approach to problem-solving. While the term ‘design’ looms large in the construct, the approach has well and truly moved from the realm of tangibles to the more nebulous domains of life and business.

Today, we are witnessing the approach successfully adopted in milieus—ranging from improving sanitation standards to encouraging employees to return to offices post the COVID-19 pandemic.

One of the unique and pragmatic aspects of design thinking is its simultaneous focus on human desirability, technical feasibility, and business viability.

Tim Brown, former chief of IDEO, defines design thinking as “a human-centred approach to innovation, which draws from the designer's toolkit to integrate the needs of people, the possibilities of technology, and the requirements for business success.”

The traditional model of design thinking

The said image is etched in the minds of scores of design thinking practitioners and enthusiasts alike. It’s elegant and comprehensive, and by looking at some of the failed innovations, you can appreciate how they missed out on one or more of these three dimensions.

For instance, the ambitious Tata Nano failed on the measure of human desirability, where the customers sought prestige from their first car and least of it labelled as owning the ‘world’s cheapest car’.

The likes of Kingfisher Airlines and Jet Airways struggled to keep their operations viable, although they scored high on customer desirability and had a battery of patrons.

The more recent case of Big Bazaar only adds to the argument that a happy customer doesn’t automatically lead to a profitable business.

And then we have the likes of Roomba Robot and Roti Maker that fell short on technical feasibility, especially in an Indian context.

However, one product that could cross the chasm during the pandemic was the dishwasher. From scoring low on desirability and feasibility, it could convince the households of a timely investment.

Bosch, one of the leading dishwasher makers in India, has to thank Covid for at least one reason. But, the three parameters don’t complete the picture. We need a fourth lens—exponential impact.

Think of a situation where an idea scores very high on the parameters of human desirability, technical feasibility, and business viability and yet, the idea may fall grossly short of creating an impact.

Case in point, the recently launched iPhone 13 in green colour. Does it excite the customer? Yes. Can Apple produce it profitably and quickly? Again yes. But does it produce the desired impact both for the company and its loyal customers? Certainly, not.

The dominant trinity model of desirability-feasibility-viability doesn’t do justice to the pursuit of radical, let alone disruptive innovation. Interestingly, a radical innovation would score low on some of the parameters, especially business viability, to begin with, and yet, if the impact is huge, like a 10X impact, the idea must still be pursued.

Similarly, for disruptive innovation, there would typically be a thumbs-down from the incumbent customers, and yet the company has all the reasons to go ahead with it as the idea may yield a significant competitive advantage and often leads to the creation of entirely new value streams.

Think of the case of QR code-based, UPI-based transactions, where the impact far out shadows the yields on desirability, feasibility, or even viability. Often the customer doesn’t know the benefits of a particular innovation or a feature.

Think about the utility of Bluetooth in in-car entertainment or GPS in navigation. Customers can’t fathom the impact such technologies could have unless the use cases emerge and adoption picks up.

The angle of impact is even more pronounced in the social sector, where an idea’s business viability is difficult to argue, and several customers (read stakeholders) to please.

An idea that might have very low business viability and even lesser customer desirability may be a winning bet if it can lead to a significant societal impact. Think about the banning of single-use plastic in cities like Bengaluru. It is costly for all parties involved—customer, retailer, transporters, etc.—but became a winning idea once its adoption picked pace.

Even in the corporate context, by introducing the fourth dimension of exponential impact in the evaluation rubric, you raise the stakes for all involved and aim for high-impact ideas.

For instance, all incremental ideas or those around facelift or minor modifications would easily pass through the mix of desirability, feasibility, and viability, but not impact, and that’s where everyone would be pushed to look at some serious bets, a more robust portfolio of ideas.

In summary, the extant practice of design thinking, by its continued focus on the triad of human desirability, technical feasibility, and business viability, ends up discounting radically superior ideas.

Both breakthrough and disruptive innovations call for a different lens to be adopted, and by introducing the axis of impact, especially exponential impact, you save yourself from low-balling your innovation efforts.

It has an obvious implication in the non-for-profit sector but also has immense utility in the commercial context.

Edited by Suman Singh

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of YourStory.)