The breathless hunt for a lost darshini, has COVID-19 devoured it?

This edition of 'SMBStory Specials' explores the impact of COVID-19 on MSMEs and resultant shutdowns. Follow us on the hunt to find a humble roadside eatery that used to be the buzz of a local neighbourhood.

(Illustration by Gnana Selvam)

Narayan was not a man in a hurry. As the proprietor of Sri Rama Darshan eatery that served the South Indian equivalent of fast food, his manners were slow and measured -- something one would expect of a seasoned golfer.

From the time that his little shop opened at the crack of dawn to the time that he shut it late afternoon after the lunch hour rush, the 48-year-old proprietor, in his pristine white half-sleeves shirt and panche (dhoti) rolled up over his knees to allow him easy movement, was on his toes with the single-minded focus of ensuring his customers return daily.

The eatery would start buzzing from 7 am onwards. There were the regular early morning walkers eager for filter coffee to lubricate their throats following animated political debates. Then there were the office boys and autorickshaw drivers grabbing a hurried breakfast of idlis and vangibath before letting the busy day swallow them whole. Late morning hours one could find the usual suspects like the IT night-shifters, who would saunter in at 11 am and opt for the meals or carry a parcel of masala dosa home to be eaten relishing a new video on YouTube.

Narayan and his staff of three had their hands full. There was no time for the proverbial fly-swatting. Located in a busy neighbourhood in Bangalore, which is a hybrid of residential and commercial properties, Narayan’s Sri Rama Darshan hotel no doubt had stiff competition from other darshinis housed in the BDA Complex down the road, not to mention the unending list of similar eateries available on online food delivery apps.

Nothing could faze Narayan though. Not even demonetisation. He would smile in response to repeated pleas by customers who were inclined to make digital payments. It was only recently that he had introduced Paytm. He could not understand what the fuss was about. Wasn’t his shop always crowded? Didn’t all the food that was made fresh every morning finish by the afternoon? Didn’t the same people keep coming back to his eatery?

He didn’t want this ‘IT crowd’ to complicate things for him. Once he would pull down the shutters at 3 pm, all he could think of was to go back home to his reclining chair and read the day’s newspaper. His two school-going children and his wife of 20 years knew better than to disturb him when he dozed off with the newspaper on his face. Narayan guarded his ‘alone time’ as he would a precious object. All that hard work was a small price to pay for this success.

Narayan's darshini (the first shop on the right) was shut down early this year. (Photo by author)

And then, COVID-19 struck. Narayan had a rude awakening. The unseen, unknown enemy was leaving death and destruction in its wake. Like other small businesses, Narayan was used to a day of bandh announced by protesting unions and political parties, but the concept of an indefinite lockdown was unheard of.

As the days progressed into months, the uncertainties increased and the crowd at his eatery started dwindling. He came to understand that the larger darshinis could still manage to run because they were delivering online. At his own shop, he was concerned about the welfare of his health and those of his staff and customers. He had barely managed to get used to cooking with a mask on and trying to ignore the customers who had theirs covering only their chin.

The day’s collections were not adding up to the total of what he used to earn before COVID-19. He missed paying his monthly rent for the first time since he had rented this place 17 years ago.

Sometime this year, he pulled down the shutters for one last time never to return.

Had he been admitted to hospital or was he among those thousand others who had waited in vain for a bed with a ventilator and oxygen cylinder just a few weeks ago?

Had he gone bankrupt? What had become of him?

Road wreckage

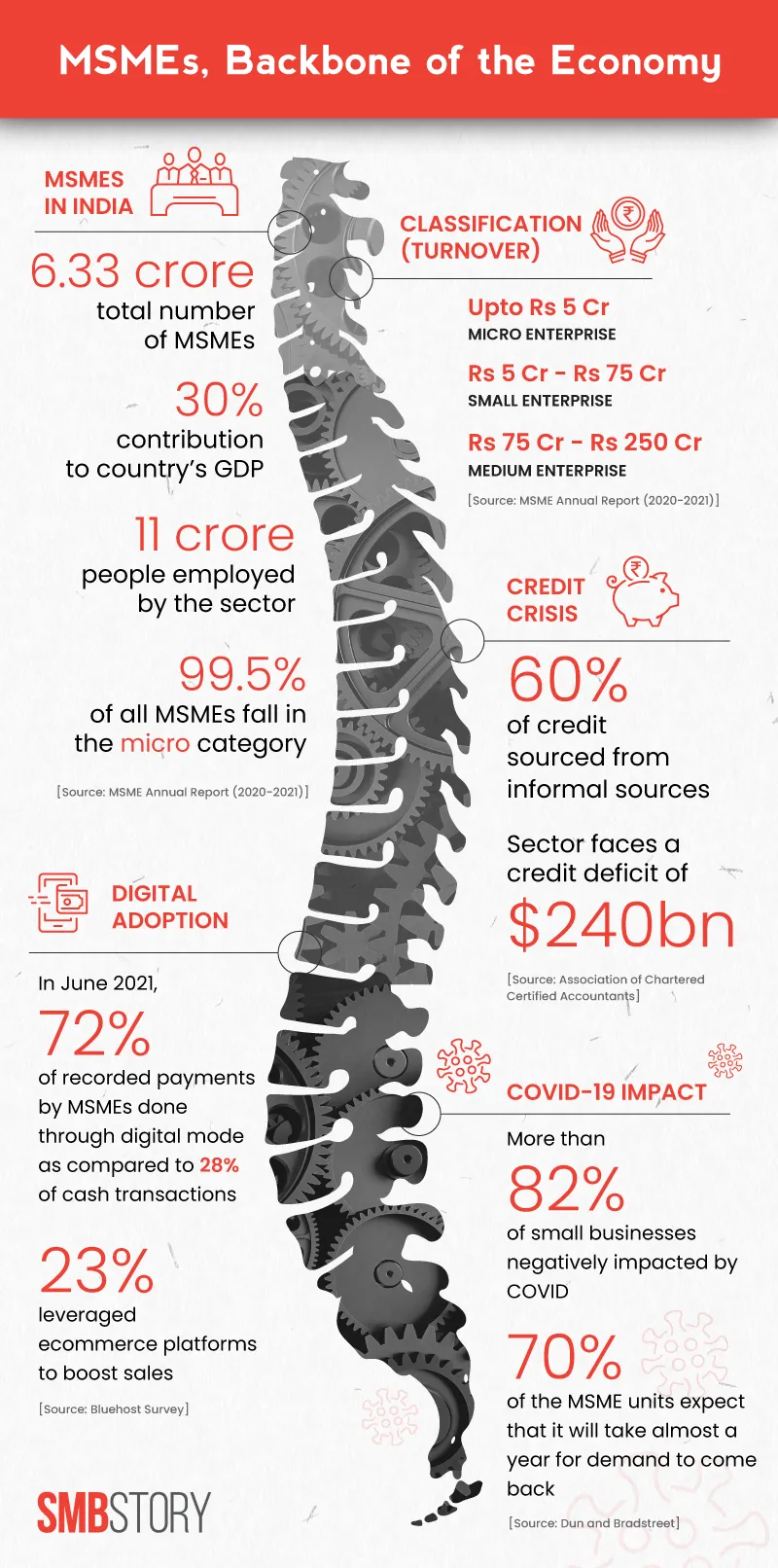

Unfortunately, Narayan’s small enterprise is not the only one whose fate hangs in balance. There are hundreds and thousands of micro, small, and even medium enterprises that are on the brink of closure or have already shut down. There is no clear centralised data available right now, but many surveys done by independent industry bodies indicate that 25 percent of the 63 million (6.33 Cr) MSMEs in India face closure due to COVID-19 lockdowns and restrictions.

A recent Dun and Bradstreet survey indicates that more than 82 percent of small businesses have been negatively impacted by COVID and that 70 percent of them expect that it will take almost a year for the demand to come back.

One doesn’t have to go far to comprehend this disturbing trend. The Hosur stretch on the Karnataka-Tamil Nadu border dotted with numerous noisy auto ancillary and textile hubs have gone silent. Some of these hubs like the textile units employing more than 1500 women run by LabourNet, a social enterprise that enables livelihoods for the informal sector workers, have shut down. Top brands and companies in Bangalore and Gurgaon outsourced work to these units, including to the hubs run by LabourNet in Haryana.

“All of them are shut. There is zero work,” says Gayatri Vasudeva, Co-founder and CEO of LabourNet. “These were solid and high-value production units with 50 odd machines for work involving denim jeans, quilts, and leather,” she adds. Once that work dried up, they tried to pivot to making masks and bags. But the per-unit price for masks cannot compensate for that of denim. Says Gayatri,

“It sounds good on paper, but the units could not survive by making just masks and bags.”

At its auto ancillary units too, the scenario is grim. The second wave-induced lockdowns saw an almost 80 percent dip in LabourNet’s on-roll workers. “From whatever angle I look at it either the factories do not have work or the workers have gone back to their villages or other places to find work. Bangalore, Chennai, and Pune are the three hubs where I can clearly see the impact,” Gayatri shares her findings.

Besides these, there are plastic recycling units and similar micro enterprises with turnover between Rs 1 crore and Rs 5 crore that are struggling to keep alive. That’s a lot of wreckage in just a small stretch of the Hosur border.

This does not look good

Closer to Narayan’s eatery is a small beauty salon run by a woman who moved her establishment here last year because the rent was lower than the commercial property she was in earlier. Once the lockdown restrictions were eased in Bangalore in June this year, she was eager to reopen her salon. But before she could figure out how to bring back her customers, she had to assess the damage. There were products and materials that had long passed their expiry date. Equipment like hairdryers and other electronic items needed servicing, not to mention she would have to single-handedly spruce up the place and make it cozy again for her customers.

“There are direct losses and then there are what we call indirect losses,” offers KE Raghunathan, Convenor of Consortium of Indian Associations and former national president of All India Manufacturers’ Organisation. “Direct loss is quantifiable. But what about the losses that are not quantifiable? For example, maintenance of the raw materials, perishable goods, machines that have stopped working because of no maintenance,” he asks.

The wellness and salon industry has been dealt a big blow and the ugly picture is there for everyone to see. “In our kind of business, the biggest challenge is opening and closing the salon based on last-minute directives from the administration. It is not easy to bring back the trained staff who may have left the city, and hire part-time people. Our customers ask for specific service providers, so that becomes a big challenge,” says CK Kumaravel, Founder of Naturals group of salons.

He has been firefighting for the 614 franchises of Naturals since the pandemic hit. Of these, six have totally shut down. “In the first month of lockdown last year, all the salons gave 100 percent salary to their staff, in the second month, it came down to 75 percent, after that 50 percent. But this lockdown, the reserves have depleted for many of them and there is no ability to borrow. For the past six months, all the salons have been making losses, but they are carrying on as long as there’s cash flow,” adds Kumaravel.

The All India Hair and Beauty Association has 75,000 salons from across the country under it of which 13,900 (3000 in Mumbai, 1200 in Tamil Nadu, 1500 in Delhi, 2200 in Kolkata, and 6000 in the rest of the country) have shut down after the pandemic hit. Anthony David, vice-president of the association, says among these are both big and small names but it is difficult for businesses to come out and say that. No one wants to publicly admit that their business has folded up. What will people say?

Packing bags

But when VP Harris shut down his 65-year-old family enterprise Witco India Pvt Ltd early this year, people’s reaction was the last thing on his mind. The public admission that they were forced to close down because of COVID-19 was followed by an outpouring of sympathy and customer support. “I was overwhelmed with the kind of reaction that we received when the news was broken by the media,” Harris tells me over a telephone call from his brother’s house in the outskirts of Chennai.

The Chennai brand had become synonymous with quality bags and luggage and it was a must-stop for people especially those travelling abroad. From selling unique handcrafted pieces when it was started by Harris’s father in 1951 to becoming a luxury brand of top global luggage brands, Witco had survived many upheavals, including the 9/11 bombings in the US and the 2008 economic slowdown. “These events had impacted our business greatly because foreign travel was disrupted,” he states. But the pandemic was a blow that Witco could not withstand.

The process for shutting down the business was gradual and had begun last year when the first lockdown was announced and international travel was banned. One by one their 11 showrooms in Chennai were closed. “Our LIC gratuity scheme helped us with settling all our staff (50 in number) accounts. I have no NPAs because we paid up all our loans on time. Some may say I was not a clever businessman. But we could not afford to burn our money. For one whole year, we had not made any sales. There was no cash flow,” he rues.

Harris seems to have taken both the good wishes of his customers and speculations of fellow businessmen in his stride. As he waits to set up another business in a totally different sector -- he has been inquiring about land prices in Kerala -- he is keeping himself busy writing about the economy and sipping his evening coffee in peace.

Something that Narayan of Sri Rama Darshan hotel perhaps has not been able to in the past 15 months now. His neighbouring kirana shop owner promises to help trace his new phone number for me. It could be that he has moved elsewhere or returned to his native village, suggests the shop owner. I nod in agreement.

The backbone’s hurting

It is interesting how the MSME sector has been fitted with the backbone metaphor for a long time now. To their credit, those in power who coined the term were looking at the sheer size of this sector and the employment it generates (See chart below) to come up with this clever moniker.

(Graphics: Winona Laisram)

Reportedly, 99 percent of businesses in India are MSMEs, and two-thirds of these fall under the informal and unorganised sector, which means they run their business with gold loans, credit card loans, and personal loans.

Did Narayan also start his humble eatery by taking out a gold loan? How did he manage to raise successive capital over the years?

A 2018 report by the International Finance Corporation, which is part of the World Bank, says the formal banking system supplies less than one-third of the credit needs of MSMEs. The reason for such a low percentage is because of bad loans, lack of business documents, account statements, and tax returns.

At a somber virtual press conference organised by the Consortium of Indian Associations (CIA) industry association leaders shared the plight of MSMEs in their respective regions -- their message was loud and clear that urgent measures were needed if the backbone of the Indian economy is to be saved.

“You cannot prescribe Horlicks when it is oxygen that is required,”

Raghunathan, Convenor of CIA, said candidly. A survey of 81,000 self-employed and micro/small businesses from across India found that 88 percent of them were yet to avail of any stimulus package announced by the government following the COVID-19 induced lockdowns (see chart below). This was either due to ineligibility or because they were unable to entirely fulfill the strict criteria for availing the benefits.

(Graphics: Winona Laisram)

It’s true one cannot prescribe the same medicine for everyone. Different categories of MSMEs require different solutions.

In May, the government had rolled out a slew of initiatives, including the Rs 3 lakh crore Emergency Credit Line Guarantee Scheme (ECLGS) collateral-free loan scheme for MSMEs. In the 2020-21 Budget announcement too, a few measures like the turnover threshold for audit for MSMEs was raised to Rs 5 crore, and the Goods and Services Tax (GST) exemption limit was doubled to Rs 40 lakhs in annual revenue, which meant that MSMEs with an annual turnover of Rs 40 lakhs or less are not required to pay GST for products and services.

But industry leaders feel this is too little, too late, especially when the GDP is contracting by -7.3 percent, the capacity utilisation is only 59 percent, retail inflation has jumped up to 6.3 percent, and the per capita income is lowest in the last five years. In such scenarios, governments are expected to provide assistance to businesses and not loans, they say.

One of the reasons that MSMEs are feeling the heat most is that even in the pre-COVID-19 years, things were far from perfect. The sector, especially the micro and small businesses, is still coming to terms with the demonetisation and the imposition of GST. Moreover, these businesses continue to be governed by complicated and outdated laws and dispensable compliances, industry associations pointed out.

They recommend that the government should redraft these laws and suggest amendments so that each sector gets its specific prescription for recovery.

Some measures outlined by the associations include relaxation in certain GST norms, pending payment collections and extensions, NPA classifications, refinancing options, opening fair price shops for raw material supplies, ban on exports of steel and cement for six months, increase in ECGLS allocation, and more.

There are a lot of uncertainties to tackle at the moment, including questions like what will happen tomorrow? How long will it take for everyone in the country to be vaccinated so that the economy can open up completely? Then there is the uncertainty in operating their own businesses. How much raw material should they buy? Are there enough funds to buy that? Assume they have the means to buy the raw materials, but where is the demand? Where is the cash flow? Do they keep their labour or let them go? Where do they turn to if they are owed small amounts like Rs 2 lakh when the other party has shut shop or is not answering their calls?

Take for example, the 26-year-old business owner who ran a successful cafeteria in an IT business park in Chennai. He was making Rs 10 lakh a month before everything came crashing down because of COVID-19. It looks unlikely that the IT park will open anytime soon as most companies are functioning well with their work-from-home directive. This young business owner has lost everything and is struggling to even pay his daughter’s school fees.

“In this sector alone, there are lakhs and lakhs of people who have become jobless -- cafeterias in IT parks and canteens in colleges. On one hand, he has loans to repay, on the other hand, he is being hounded by his employees. He says he feels like committing suicide. How do we help him?” Raghunathan asks, stating that every day, he gets calls from business owners pleading for help.

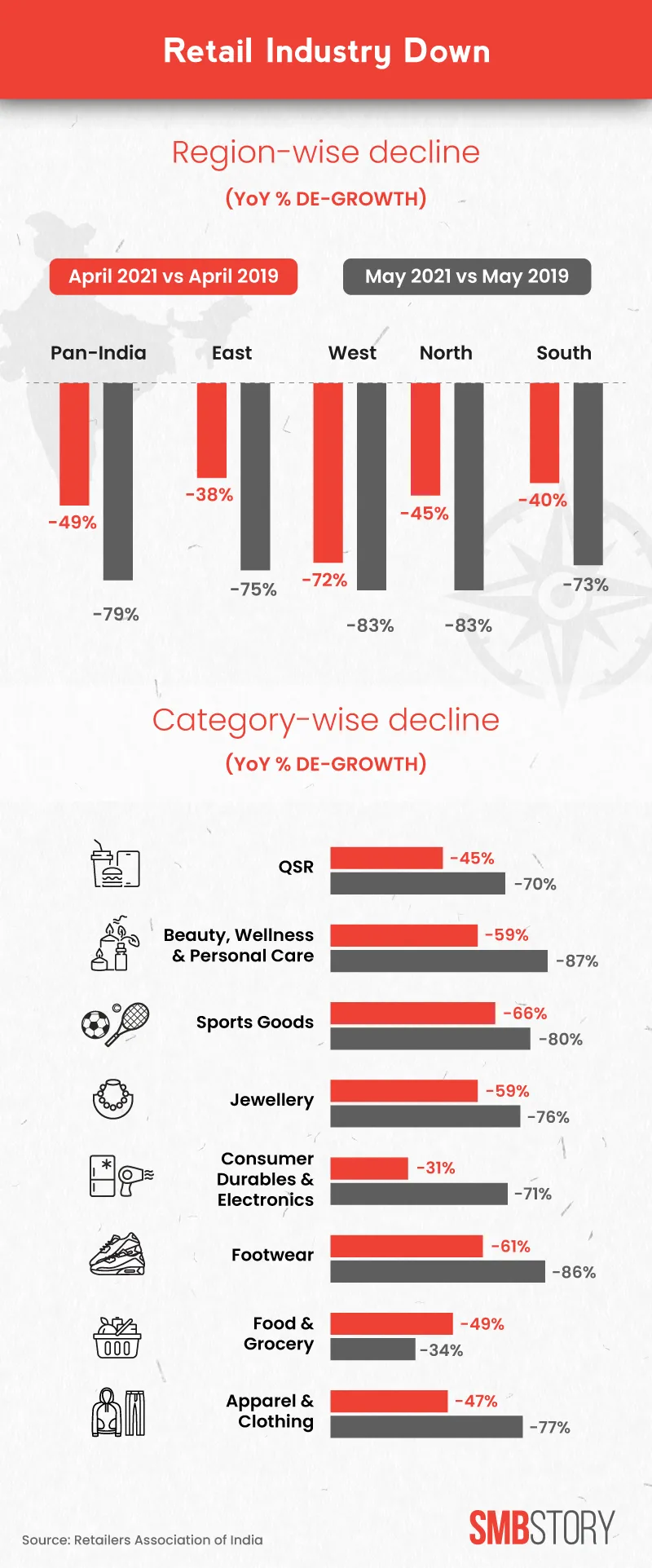

The retail sector alone has a huge impact on direct employment with 45 million people working in this sector.

There are around 15 million retailers in India and all of them are sweating not so much from the rising heatwave, but the prospect of looming lockdowns.

“It is not feasible to keep a shop open only for a few hours in the day,” says Kumar Rajagopalan, CEO, Retailers Association of India (RAI). The expenses are 100 percent (whether you open it for the whole day or a few hours in the day) but the revenues have declined to 30 percent (see chart below). If the shops are allowed to remain open during business hours, it helps in avoiding crowds. The less time a shop is open, the more the crowding, he adds.

(Graphics: Winona Laisram)

“Most retailers are hoping the landlords will waive off rentals and they can manage by giving part salaries,” adds Kumar. On the government’s new directive recently including retail and wholesale traders under MSMEs, Kumar feels it will have a “structural impact for the sector, helping it get formalised by giving better finance options.”

There is no doubt that small businesses need better credit facilities, better marketing support, and better adoption of technology during these challenging times, as the Dun and Bradstreet report points out.

The path ahead

Had Narayan paid serious heed to customers telling him to adopt digital payments, would he have been in an advantageous position to salvage his business? I hope to get the answer to the question soon.

Last year amidst COVID-19, the government had launched the Udyam registration portal, its new portal for MSME registration. As of May 16, 2021, 30 lakh MSMEs have been registered on the portal. Interestingly, about 28 lakh registered enterprises were micro units, 1.78 lakh small enterprises, and 24,657 mid-sized enterprises.

Considering the new Udyam registration portal is integrated with the Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT) and GST networks along with the public procurement portal Government e-Marketplace to make “end-to-end MSME registration paperless”, the MSMEs registering under it can be a potential target market for firms offering digital transformation tools, including fintech products.

Rajiv Pathak, Business Head-MSE, of Ujjivan Small Finance Bank, says the digital adoption among MSMEs is increasing and more than 55 percent of the customer-onboarding process at his bank is digital now. On his frequent visits to MSME hubs, he has witnessed a positive shift towards digital adoption. “In the Tirupur textile hub that I visited recently, many small manufacturers are eager to jump on the ecommerce bandwagon and tie-up with the bigger online ecommerce players. They are all focused on cash flow at the moment to keep their businesses afloat,” he says.

Digital transformation has long been coming, but with COVID-19 here to stay, the time to make it happen is now if it can benefit small business owners like Narayan.

As promised, the kirana shop owner gives me his whereabouts. Narayan has moved his shop to a different location. I heave a sigh of relief and set off to meet him. The eatery looks new and shiny compared to his earlier one, and surprisingly bigger too. There is only one customer grabbing a late breakfast.

We have never spoken in the past. But these are extraordinary times. Narayan smiles at me in recognition. I tell him that I feared he had permanently shut down. He says it has been only 15 days since he reopened at the new location. For the five months that he had shut his shop, he had gone home to his village in Udupi. And yes, the rent is lower here and yes, his business has taken a beating, he says, but his smile does not fade in front of a potential customer. He hopes he can list on the online food delivery apps, but for that, he will have to increase his staff first. It’s a vicious circle, really.

He looks tired but his attention to detail is as focused as it used to be. He takes his place behind the cash counter, giving instructions to his kitchen staff simultaneously. I pay for my order through UPI and carry my plate of idlis and glass of coffee to an empty table overlooking the main road. I remove my mask and take a sip of the bitter-sweet coffee.

Narayan behind his cash counter at Sri Rama Darshan. (Photo by author)

Edited by Saheli Sen Gupta and Tenzin Pema