Meet the 17-year-olds who have won a global award for their ML model that detects genital skin cancer

Aasimm Khan and Sidharth Jain were among the top prize winners at International Science and Engineering Fair, US, for their innovation that helps in remote early detection of genital skin cancer.

What were you doing when you were 17 years old?

Ask Mumbai-based teens Sidharth Jain and Aasimm Khan, and you will get a straightforward answer: building a mobile-based app that helps in the early detection of genital cancer. The Class 11 students at Jamnabai Narsee International School recently won one of the Grand Awards at the US-based International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF).

Their innovation – Remote Identification and Detection of Genital Skin Cancer (RIDGE) - was given the Grand Award fourth place in the annually-held global innovations fair’s ‘World ISEF Regeneron 2021 Bio Medical Category’.

They previously placed among the top 10 at the Microsoft Innovation Challenge, one of the largest innovation competitions for students from across the globe. They won the Junior Imagine Cup with their project for using AI for Humanitarian Action in detecting genital skin cancer.

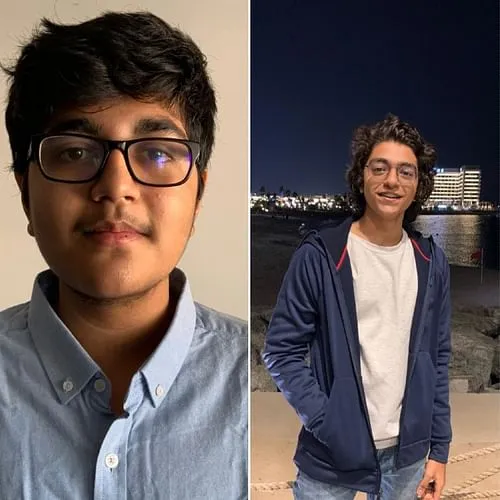

Two Mumbai-based students Aasimm Khan and Sidharth Jain were named Grand Award Winners at the ISEF 2021

A personal mission

For Sidharth, the journey to the innovation began with a deep personal loss. “My grandfather had been diagnosed with Parkinson's. During the lockdown, he became completely bedridden, and after a couple of months developed bed sores. The bedsores eventually became cancerous,” he says in an interview with Social Story.

Sidharth and his mother were in constant touch with doctors over Facetime because COVID-19 restrictions meant they could not take his grandfather to the hospital to even do a biopsy. He passed away soon after. “We never found out what caused the cancer and what type of cancer it was.”

The lockdown posed another challenge for the classmates as all the research and collaboration for the project happened remotely.

“We spent the first couple of months brainstorming and working with doctors to understand what cancer is and how it happens. Our main aim was to create something virtual that everybody could use while sitting at home,” says Sidharth, adding that their goal was to be able to help doctors do remote assessments of people, who like his grandfather, were not able to reach the hospital to get a timely diagnosis and treatment.

According to Aasimm, they decided to focus on genital skin cancer because many people were hesitant to discuss lesions in their private parts, and even more reluctant to have a doctor examine them.

“This often results in the cancer worsening and by the time they seek help, the cancer is way past the treating stage. We wanted to really break that barrier of privacy by providing a tool that will aid in earlier detection. In our research, we realised that 81 percent of people aren't really comfortable showing the lesions to doctors and the main barrier is privacy. So we developed RIDGE, where a person can scan themselves and share the images with the doctor for analysis,” he says.

A challenging task

However, the students needed guidance in navigating such a complex area of research.

“Since we were working on a technology that was based on remote diagnosis, we needed to make it easier for an analysis of the image. Our first option was to use image processing and machine learning. But the sheer size of the database of images made us realise we needed guidance,” Sidharth says.

With the help of mentors at On My Own Technology (OMOTEC), a Mumbai-based learning centre that teaches science, technology, research, engineering, art and maths (STEAM) courses, Sidharth and Aasimm were able to use machine learning to detect abnormalities and understand various types of cancers.

“Though they taught us how to go about the process, we worked on it ourselves, because we believed that it would truly be ours only then,” Sidharth says.

“OMOTEC also helped us connect with the doctors we worked with to develop RIDGE. They also helped us prepare for the competition and how to present our project. Since it was such a huge project, they helped us focus on the relevant parts that we would focus on. We were up with them till 3 am finalising everything. I think 3 am coding really boosted our friendship,” Aasimm says.

Explaining the complexities of the year-long project, Reetu Jain, Chief Mentor and Founder of OMOTEC, says, “When you're working on such dynamic projects being cross-skilled is very important. The mapping kit they have made is actually a Computer Aided Design (CAD) model. Sidharth and Aasimm actually learned 3d Design. They also know Python programming, Open CD, and machine learning models. They combined all of this together to come with a complete solution. Combining pure science knowledge with technology makes a lot of difference.”

The teens also conducted a lot of research on female cancers in the vulva and other cancers in the genital region.

Reetu says one of the big challenges while using image processing to identify the features of the lesions was false positives.

“They had to be very careful in terms of ensuring that they got the features of the lesions right in terms of classifying them as malignant, pre-malignant, or benign. They've put a year-long effort, starting in May 2020. They’ve done a really good job and we are proud of them,” she says.

Explaining the mentorship process they underwent, Reetu says, “We work with skilling students. When they understand how Python or image processing is used in real time in the industry, it opens up their minds. Secondly, we brainstorm with students to identify the problem; it should be a solvable one.”

She adds that it’s very important to keep students grounded and help them understand the technical nuances of executing a project.

“Many times, especially with boys in robotics, we have fun thinking about Transformers or Avengers. I can't tell you the kind of robotic solutions that come out,” she says, adding that both Sidharth and Aasimm showed immense maturity in their focus on the project.

However, there were several challenges.

Aasimm explains that a database for genital skin cancer was really tough to find. “When we were starting up this project, we weren't finding any good source images. We searched 15-20 websites and got only 5,000 images. By the end of it we also found a data set ISET, which had 24,000 images, and we are going to deploy that in our models. We currently have an accuracy of 83 percent, which is better than some of the ways of identifying genetic skin cancers. But by adding these new datasets and approaching more hospitals, we aim to get our accuracy up to 95 percent.”

Sidharth Jain (left) and Aasimm Khan, the two Mumbai-based teens who are developing a technology for remote skin cancer diagnosis

The road ahead

Sidharth says that they are planning to include personalised patient details such as age, gender, and location to enhance the results.

“For our project, we needed a classified dataset that indicated whether the image was malignant, benign, or basal cell carcinoma. There are so few resources available for genital skin cancer. We recently found a dataset that had clinical information as well so we will be including all this to get more accurate results. Our mentors helped us create our own machine learning model.” He adds that despite having everything ready, COVID-19 has prevented field tests.

“We got invites from Tata Memorial hospital to actually come and test our ML models with them, but could not because of COVID. But as soon as things open up, we're planning to deploy a model for two years with doctors. We also don't have an accuracy value for our pressure mapping because we need to conduct medical trials,” Aasimm says.

He and Sidharth are also making plans for university, where they will continue to develop the project

“We are not assigning roles completely, but we've decided that I'm going to be conducting research with professors to radically improve the accuracy of the project, while Aasimm wants to go to business school, so he's going to be handling that aspect of the project,” Sidharth says.

The duo has filed for provisional patents on the technology.

“This will give us some time to work on it professionally, get it medically teste, and approved. By the end of the 18 months, or by the time we finish up the project, we will apply for the main patents to completely secure the project in our name,” Sidharth says.

Edited by Teja Lele