These tech solutions are saving lives of pregnant women and newborns in rural India

Senthil Kumar is the founder of JioVio Healthcare that has developed SaveMom, a range of devices and apps, and works with government agencies and NGOs to offer 1,000-day care for mothers and their newborns in four states.

In 2016, Senthil Kumar’s sister Manimala, who was pregnant, was missing her antenatal appointments owing to the distance from her village to the city hospital. There was also a long waiting time to meet the doctor.

“My sister would panic at every little thing and take the entire family with her to the hospital. I wanted to help in some way to reduce her anxieties and also motivate her to go to the hospital regularly,” Kumar tells SocialStory.

SaveMom's suite of solutions

An engineer in constant innovation mode, he met Manimala’s gynaecologist to understand what each check-up entailed. She explained that vital parameters like blood sugar and blood pressure needed to be tracked. He hit up on an idea – he bought a blood pressure monitor and a blood glucose measuring device and replaced their display screens with a blue chip.

“I also developed a mobile app that would text my sister’s readings to the doctor for evaluation. It would also send her reminders on when to take medicines, and also provide tips on diet and nutrition,” he says.

The app would also alert Manimala’s husband in case of an emergency and also book a cab, if needed.

Developing tech solutions

This small prototype laid the foundation for JioVio Healthcare and SaveMom, a suite of IoT-based maternal healthcare solutions that would go to become a case study at Harvard Business School.

The Madurai and Bengaluru-based startup, which started commercial deployment in 2019, has impacted more than 36,000 pregnant women (who completed a 1,000-day care programme) in tribal villages of Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, and Maharashtra. Currently the platform has more than three lakh mothers.

A native of Madurai, Kumar started his career in Samsung, working on the Galaxy S1 phone. Post this, he joined Qualcomm in 2013 to work on new generation wireless technology, including 4G and 5G.

At that time, he wanted to develop an IT ecosystem in the city to enable companies to look at the city as a viable option to start up in the future.

“Every weekend I travelled to Madurai and along with my sister, helped 200 girls prepare for the Technovation Challenge organised by the UN. Our focus was on identifying local and community issues and find a tech solution for them. Since the girls didn’t have passports to travel, a team from San Francisco came to Bengaluru to organise the challenge, which they won with ease,” he shares.

This led to Madurai Kavalan, an SoS app used by 1.5 lakh people in the city alone, which was later developed as a state-wide application.

Taking ante-natal screening to the doorstep

Tribal women waiting at a Public Health Centre (PHC)

While developing the prototype for use by his sister during pregnancy, Kumar believed that the intervention could help more women, especially those in remote regions who had little or no access to healthcare facilities.

On research, he discovered that globally more than 800 women (including around 75 in India) die preventable deaths due to pregnancy-related complications every day.

While undertaking on-ground research in tribal villages in Ooty, Kumar understood that pregnant women had to travel 10-12 km to reach the nearest Public Health Centre (PHC). Sometimes, they had to wait the entire day to meet the doctor. These challenges stopped them from visiting the PHC for ante-natal check-ups.

“I spoke to a mother who had lost her first baby and was in her second pregnancy. I went to the PHC to get details on what went wrong the first time and was flabbergasted to note that the baby had been listed as born and the family had received Rs 10,000 from the government,” he says.

He took a copy of the mother's health card back to the couple and realised they were unaware that the government provided money for a pregnant woman’s care.

Kumar quit his job at Qualcomm in 2016 and set about developing JioVio Healthcare by collecting data on pregnant women in villages on the Kerala-Tamil Nadu border. There too, he found the data to be inaccurate. To counter this, he proposed the use of technology in antenatal care for women who do not frequent PHCs as much as they should.

“We began providing devices and a mobile application to the health worker. If a woman is pregnant in the community, the platform would keep a check if she’s visiting the PHC. The health worker will visit the woman’s home along with the devices and capture the data digitally, and transfer it via Bluetooth onto a mobile,” he elaborates.

Doctors can access the information via the doctor’s portal, and classify the mothers as high-risk and low risk. The health workers also distribute iron and folic acid tablets to low-risk women and accompany high-risk women to the PHC for ultrasound and other tests.

Innovations for accurate data and screening

The Allowear bracelet

However, data manipulation became rampant when health workers began using the devices on their colleagues and recording the data. To reduce this, an incentive of Rs 20 was given for every ante-natal check-up done.

Though this reduced instances of manipulation to some extent, Kumar wanted to be sure there was interaction between the health worker and the pregnant women.

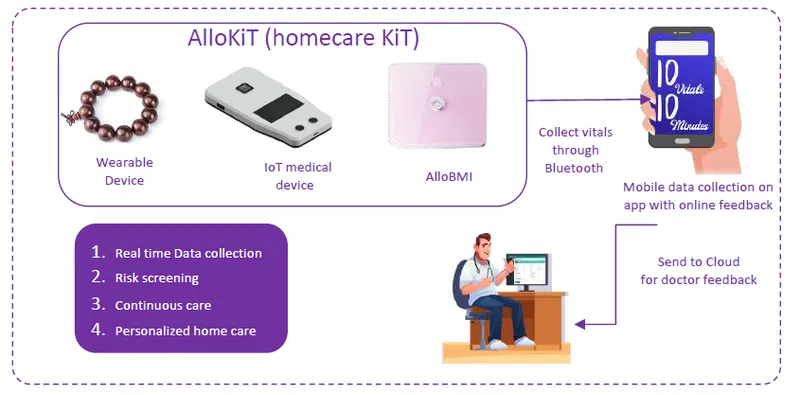

He struck upon the idea for a unique jewellery-inspired smart wearable device called Allowear that a pregnant woman has to wear 24x7. With a six-month battery life, it tracks sleeping, steps, and gives reminders for medicines for a 30-day period. When the health worker visits her, she retrieves the data via Bluetooth and uploads it onto the cloud for doctors to access.

While the intention of the health worker and the pregnant woman being in close touch was successful, the use of the bracelet also was not without incident.

“At times, we saw that a woman had walked 20,000 to 50,000 steps in a day and we assumed the wearable had been stolen. When we visited her home, we found out that her husband was wearing it as he thought it was a fancy accessory,” Kumar says.

To address this problem, JioVio designers studied local cultural practices and inspired by the bracelets made from rudrakasha seeds worn by Adivasi women in the interior villages of Wayanad, designed a new version of Allowear. This worked. In a village in Kerala's Wayanad, where infant mortality rates were high, the team began receiving more reliable data and saw a 38% increase in the average weight of newborns.

Currently, this wearable is provided only to women with high-risk pregnancies. After the child is born, the bracelet is passed on to him/her for neonatal and postnatal health monitoring.

The team also noticed that family members consumed nutritional supplements given to pregnant women by healthcare workers. They addressed this problem by developing a formulation that does not taste good and does not require cooking. The formulation can be consumed by just mixing it with water.

To ease the burden of the health worker who carried a number of devices in her bag, JioVio also developed Allotricoder--an integrated non-invasive device that captures six vital information (blood pressure, heart rate, temperature, respiratory rate, ECG, oxygen saturation and glucose) digitally and sends it to AI engine for analysis. This can easily fit into a health worker’s pouch or a small bag.

JioVio also developed AlloBMI--a simple weighing scale integrated with the application to monitor the steady increase in weight during pregnancy. This was especially necessary for rural areas where women astonishingly lost weight during the course of pregnancy, leading to unnecessary complications.

The device costs Rs 1,800 and the wearable costs Rs 1,000. JioVio has collaborated with local government agencies and NGOs for providing 1,000 days care to mother and child for Rs 1,000 (amounting to Rs 1 a day) that covers 15 antenatal check-ups of the mother and post-natal care of the baby. A district can buy an annual subscription to the platform for Rs 5 lakh and there’s no limit to the number of pregnant women that can be onboarded into the system.

Reducing mortality rates

From 2017-2019, Kumar worked on the project with money received from grants from Department of Science and Technology, investment from a Singapore-based accelerator, and seed rounds from Mumbai and Bengaluru-based incubators, amounting to Rs 3 crore. The devices are manufactured by contract manufacturers in Bengaluru and Pune.

JioVio now generates revenue between Rs 12-15 lakh a month. It works with a team of 25 people, based in Madurai and Bengaluru.

“Earlier, the mortality figures were around 120-130 deaths among 100,000 deliveries. Now it’s reduced to a single-digit figure. Our next step is to introduce SaveMom in the North East where infant mortality rate is high. We have also signed an MoU with the Government of Ghana to deploy our solutions there,” Kumar says.

The accolades have not stopped coming. SaveMom Become a Design Thinking Case Study in Harvard Business School, won the SIHI Award from TDR World Health Organization for Social Innovation health initiative, is among top 10 startups selected for Google Launchpad Accelerator Program, and also won the NASSCOM Health Innovation Challenge 2.0.

However, Kumar’s defining moment in the journey is an emotional one.

He says, “I cannot forget the day when I was invited to a village and a baby girl weighing 3.1 kg born to a tribal woman in Wayanad was placed in my arms. It was the first time a woman there had delivered a healthy baby, over 2 kg. The villagers were celebrating the baby's birth. It was an emotional moment.”

Edited by Megha Reddy