Bollywood and stereotypes: Bengali-Punjabi tropes minimise rich cultures

YS Life explores the cliched approaches to Bengalis and Punjabis in Hindi and mainstream Indian cinema.

In Rocky Aur Rani Ki Prem Kahani, Karan Johar’s ‘mother’ is not all about kindness and sacrifice. Jaya Bachchan plays a rigid, manipulative and conservative matriarch who owns a mithai (sweets) empire.

The movie questions the assumed behaviour patterns of Punjabis (being rigid, conservative, and overdramatic) and Bengalis (considered to be judgemental and elitist), but still depends on stereotypes to build the characters.

Johar often casts Bachchan as a matriarch with some agency in his films. In Rocky aur Rani Ki Prem Kahani, Bachchan’s character has a hardening in her heart that reminds one of Amrita Singh’s (finer) performance as the unrelenting mother to Arjun Kapoor’s character in Two States (2014), also a Dharma Productions film.

The Punjabi mother—through Johar’s lens— is almost always harsh and unchangeable.

Similarly, it isn’t uncommon to see Bengalis being stereotyped in Bollywood, given that its culture is distinct and has been visible since the pre-Independence times.

Specific to this film, Bengalis are viewed as liberated and cultured but they remain exclusionary and elitist. In general, Bollywood films dole out a similar stereotypical treatment to the Punjabis, who are often seen as leading ultra-luxurious lives, keeping away other aspects of their community such as folk music, dancing, and even their Sikh faith.

This tendency to use cliches in telling a story is reductionist and somewhat outdated but it somehow continues to live on, even in modern forms of storytelling like OTT.

If a movie or series has a Punjabi character, one can expect them to be portrayed as loud, dumb, and even irritating (Namaste London, Son of Sardaar, Humpty Sharma Ki Dulhania). But the elements of Punjabi culture and households are seldom portrayed in an authentic manner.

For instance, Sikh prayer songs (gurbani) resonate gently, without deafening noise levels, on mornings across Delhi NCR. They are steeped in melody and offer great comfort to listeners. But none of this made it to mainstream films until recently.

Laying this on Johar’s doorstep alone is neither fair nor offers a holistic overview of cinema’s tendency to stereotype.

Shoojit Sircar, a fine filmmaker of our times, also stereotypes his own kind—Bengalis—often crafting his characters with generalisations. His characters entertain and come across as authentic but they do label a culture with some preconceptions.

For instance, in Vicky Donor (2012), when the garrulous Punjabi baraat approaches, a couple of Bengali guests at the wedding comment on their dancing, as if they were dancing like monkeys. The bride’s father advises his daughter to recognise a man through his understanding of fish.

Jayanta Das and Swaroopa Ghosh in Vicky Donor (2012) | Source: IMDB

Sircar also portrays 'typical' Bengali behaviour in Piku (2015), with the loud, hypochondriac father played by Amitabh Bachchan.

Some of what Bachchan's character does and says is socially relevant—for instance, his liberal approach to his daughter having a career and not getting married. And the scenes with soft retro Bengali music in the background as the family gathers for the evening are endearing.

But in highlighting the so-called typical elements of being Bengali—including the notion of them being tight-fisted around money—Sircar ends up perpetuating yet another stereotype.

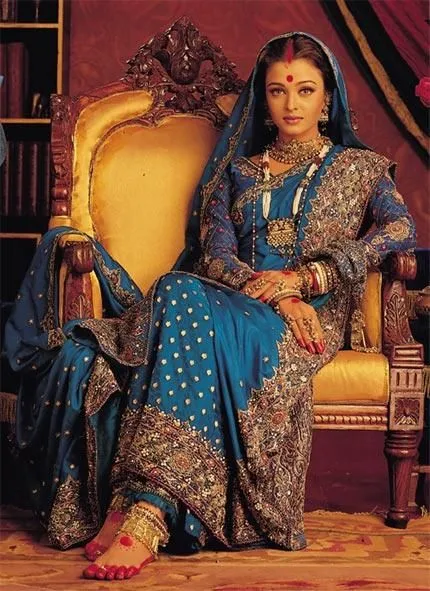

Aishwarya Rai Bachchan as Paro in Devdas (2002) | Image source: Pinterest

And then comes Sanjay Leela Bhansali. His Devdas (2002) is perhaps the most unsavoury presentation of Bengalis in recent memory—from incorrect verbiage to over-the-top reactions and melodrama.

The suffering of its central characters, reflective of a time in history, is completely lost in all the heightened cinematic flourishes, making the film feel like an overdone soap opera.

Before Devdas, Bhanshali had stereotyped Gujarati households in Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam (1999), with a frenzy of colours and dancing and incessant loud conversations. Bhansali states that his attempt, in both cases, was to create a nautanki-like environment.

The filmmaker could have toned down the volume and the colour and focused on making the characters seem closer to people in real life.

Even in his recent film, Goliyon ki Rasleela Ram Leela (2013), the hyper-Gujarati elements distract. Thankfully, the rock-solid performance by Supriya Pathak, as the cruel matriarch, rescues the film, despite its cliched approach.

India has a culture of using language, region, and caste names as identity markers. Cliches and stereotypes make for an easy storytelling trope. They remind the audience of past films and stories about these cultures and also draw a few laughs. But when popular filmmakers fall back on these elements to give their characters shape, they carry forward a culture of preconceived notions and prejudices.

When you compare these films to the recent work of younger filmmakers, you can notice an evolution. For instance, Bulbbul (2020) by Anvita Dutt deals with the plight of a young, non-aristocratic bride in a Bengali zamindar’s home with sensitivity and an element of mysticism. Here too, the women wear loads of jewellery and heavy saris, but neither their responses nor the reactions of the men are wrapped in loud stereotypes. Dutt subtly makes a point and underlines the problems of inherent bias in a culture.

In Ranjhanaa (2013), the protagonist explains his ability to win over a girl by simply wearing down her defences with his pushy behaviour and stalking. The movie is tongue-in-cheek in its tackling of male attempts at romance.

Punjab found a fresher and more realistic representation in Udta Punjab (2016), Luv Tuv Tey Chicken Khurana (2012), Phillauri (2017), and the web series Kohrra (2023). Here Punjab’s latent colours, sounds and cuisine are interconnected to the story. The flip side of dogma and the ground reality of social evils also emerge.

More commercially inclined films like Jugg Jugg Jeeyo (2022) or Imtiaz Ali’s Jab We Met (2007) and Love Aaj Kal (2009) capture Punjab’s standardised colour palette and joie de vivre but they also provide relevant context and contemporary treatment.

It is ironic that stereotyping has taken root in Indian cinema so deeply because, in the earlier years, filmmakers used the niceness and warmth of specific Indian cultures to root their characters.

Yash Chopra’s early films, for instance, cast characters as urbane, progressive, and Indian. Aditya Chopra’s Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge (1995) features an NRI family and a conservative Punjabi family without over-hyping their song, dance, or food at every turn.

A scene from Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge (1995) | Image source: Facebook

Perhaps the most relevant representation of Bengal still remains in Satyajit Ray’s work. While it is impossible to capture all of his films for reference, Agantuk (1992) gave a slice of urban Bengali life and culture, rooted in Kolkata’s upwardly mobile families, which is unmatched to date. Shashi Kapoor’s productions, be it 36 Chowringhee Lane (1981), Vijeta (1982), or Kalyug (1981), captured the nuances of Indian culture and life and this has never been revisited.

With Rocky Aur Rani Ki Prem Kahani, Johar has made a direct, if not clumsy, attempt to deconstruct the accepted norms of a family’s say in a relationship. He has attempted to draw acceptance by questioning gender bias and male privilege. With most of his films being touted as benchmarks for entertainment, it is progress. Nonetheless, the reliance on cliches makes this progress seem less fruitful.

Edited by Akanksha Sarma