Are Indians killing their traditions? Banna Creations discusses

Hot pink or a bright torquise, studded with rhombus mirrors, we’ve all received small lac handicraft jewellery boxes. Unfortunately, the Jaipur lac handicrafts is a dying industry. So is the ply-split braiding craft of the Rabari community in Kachchh, Gujarat, and silk-weaving tradition in Varanasi. As cultural trends chance, mass production becomes cheaper and rural artisans continue to be disconnected from the 21st century, India is likely to see its hundreds of handicraft traditions die out in the next few decades.

The export of Indian handicrafts was worth USD 3.8 billion in 2013-14. Still the growth is neither uniform nor exponential. In this light, it’s up to the government and private sector to milk the talents of thousands of handicraft communities — whose skills have been passed down to them over 2000 years — to create a thriving and lucrative market.

The first step in this process is to make the Indian customer realise the value of handicrafts and the hands that go into creating these crafts. If handicraft workers are not paid handsomely for their skills, there’s almost no incentive to pass these skills to the next generation. In fact, there’s no incentive for them to continue working in the atrociously disorganised handicrafts industry. The infamous habit of Indian shoppers to incessantly haggle to bring down prices already too low for artisans to sustain on is killing India’s traditions.

However, numerous startups have popped across the country to leverage the Internet to sell genuine handicrafts. One such startup is Banna Creations started by Aishwarya Suresh.

In 2011, Aishwarya decided she wanted to start an enterprise that would provide artisans the opportunity to not only earn their dues respectfully, but a means to organise themselves into a workforce. In four years of running Banna, Aishwarya has traversed across the lengths and breadths of the country to find marginalised art forms under threat of extinction with the aim of refining these handicraft skills to make them marketable on an international level. During this time, Aishwarya has both worked and lived with artisans to understand the challenges they face as artisan communities in the 21st century.

Over the years, Aishwarya, through Banna Creations, has conducted numerous exhibitions and workshops for artisans. Putting the business online has helped expand the target, too. Aishwarya says, “My typical day involves working with artisans, co-designing products with them, coordinating their delivery efforts and on the customer front, marketing and selling those products online and through exhibitions.”

Aishwarya believes that for traditional art forms to be marketed as premium products, first, the product quality needs to be very high. She says, “We tell artisans that every product needs to be perfect. We need to build that work ethic in them.”

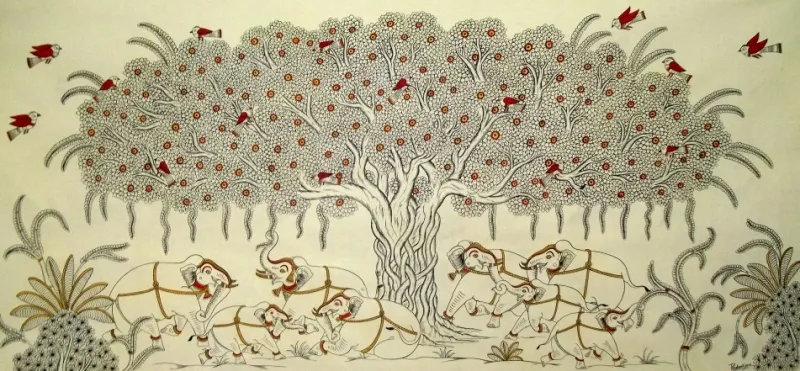

Some of the work on Banna is more than 1,000 years old. For instance, the Kasuti embroidery from North Karnataka. Aishwarya encouraged artisans to use traditional textile artforms on linen, photo frames and purses. By expanding and mordernising traditional art forms, Banna creates the diversity the industry needs to thrive and evolve.

She says, “Similarly, I started out in an offline model, relying on exhibitions as the primary channel, but realised that the ROI on digital marketing spend is lot more and used social media marketing to draw in customers and eventually moved into a full commerce model last year.”

Banna itself began with its focus on North Karnataka, but eventually spread out to artisan communities from Bihar, Jharkhand, the North-Eastern states, Rajasthan, Orissa, Gujrat, Madhya Pradesh and Tamil Nadu.

One of the biggest challenges, however, of running Banna is the scepticism within the artisan community. Long neglected, they tend to be set in their ways, and building their trust is one of the biggest setbacks. Besides this, not all artisan communities are well-organised or connected. How much an artisan earns for his skill is completely arbitrary, and dictated by unscrupulous middle men who eat most of profits. It’s not easy either that selling directly to the customer is impossible for communities who don’t have the resources to supply their products or the education to benefit from the Internet.

Customers themselves are likely not open to paying reasonable money for these crafts. There is a tendency to equate hand-made with cheap, as more and more Indians get used to buying mass-produced imitations for low prices. Handlooms, for instance, face the same problem. Whether it’s silk weavers or Dhaka muslin weavers, the mechanisation of these crafts has drastically reduced prices. Whilst in any other country, it would increase the value and prestige of hand-made crafts, in India, it seems to have done the opposite. Aishwarya says they have even walked away from transactions when contrarious customers solicit bargains and refuse to relent.

Aishwarya says, “I don’t blame them. They’ve tried and burnt their hands earlier at successfully promoting their art form, and barring a few savvy artisans, most of them are unsure of how to make a living out of their art. I have seen painters and embroidery experts switch to other forms of painting or a completely different vocation so as to earn a living. This is enough inspiration for me to do what I do with Banna.

“On the supply side, a lot of effort is needed to ensure artisans deliver quality on time. This sector is not yet organised and needs a lot of personal hand-holding, visits to the artisan’s place of work and constant communication.”

The hard work has shown. In these four years, Banna has catered to more than 25,000 customers, many of whom reside outside India (who, ironically, value Indian handicrafts more than Indians). With over 10,000 products sold, 25 workshops conducted, there’s no stopping for Banna. They even provide skills training for women in Bangalore, too, to help them gain employment.

Younger Indians are more likely to value handicrafts, and their presence online makes them a tempting and perfect market.

Banna, in Kannada, means ‘colour.’ In a way, it’s this diversity that Aishwarya’s brain child brings to the marketplace. But, beyond that, it adds ‘colour’ to the lives of Indian artisans struggling to make a living.