How to go from good governance to great governance

After having tackled issues of hygiene, sanitation, women’s and adolescent girls’ development, Dasra, a philanthropic organisation, is, now, tackling governance. Since the last few months, ‘governance’ has become a stock phrase endlessly repeated in jingoistic advertisements and by duplicitous politicians. In December 2014, Dasra released its report on good governance, Good to Great, to give a practical, than needlessly nationalistic, beginning to the move towards improved governance.

The report is an admonitory briefing of India’s consistently poor governance, but also highlights singular efforts in the direction of improving governance by local organisations.

In the report, chairman of Pirimal Group, Ajay G Piramal writes,

“To me, robust governance is a means to an end. I believe the current status

of India’s human development indicators is largely an outcome of our poor

governance record – whether on the quality of our public education,

access to good primary healthcare, or leakages in our public distribution

system and livelihood schemes… it can all be traced back to weaknesses in

the policy and operating architecture. At the same time, we do see islands

of excellence in government and among civil society organizations.”

The Economist Intelligence Unit, an independent part of The Economist Group, every year, compiles the Index of Democracy. In 2014, India was ranked 27 among 203 countries that included dictatorships, dysfunctional democracies, corrupt nations and failed states. The report labelled India a ‘flawed democracy.’ For a nation where 96.3 per cent of the population lives below $5 (PPP) a day, or 59 per cent lives below $2 (PPP) a day, a ‘flawed democracy’ leaves little to be desired.

Furthermore, in the 2014 Corruption Perception Index by Transparency International, India ranked an abysmal 85 (of 175 countries assessed). Even worse, the country sits at a low 142 (of 189) in the 2014 Ease of Doing Business report by World Bank. So, though, we may be a nation of growing entrepreneurs, we’re still a nation that’s unattractive for business.

Every hour, 200 children under five years of age die due to poor health and hygiene. In 2008, it was estimated that 1.8 million children (under five) lost their lives, mostly within the first 28 days of life. The superficial portrait of India is a glinting neon sign that points to American malls and poor Bahnhofstrasse imitations. But overshadowed by the brilliance of our chaotic, clogged and polluted Westernised cities is a grim reality of what is still an impecunious third world nation.

Even through development strides, decades of rule has still been incapable of giving India the kind of growth it needs. Even now, the government has been unable to provide 100 days of wage employment to rural households as recommended by the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005. The NREGA has only been able to provide less than 50 days of employment. It was later superfluously renamed the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act.

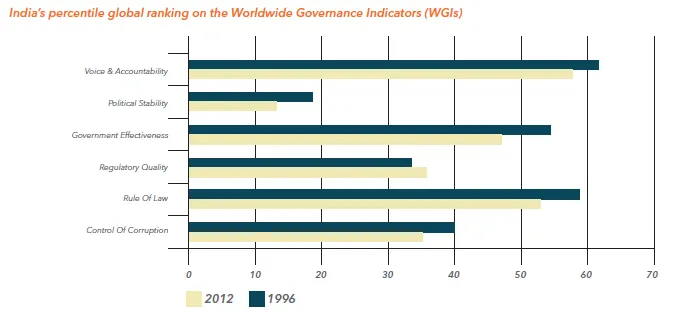

After 16 years of decline in quality of governance between 1996 and 2012, according to Dasra, progress needs to take place at all levels: legislative, executive and judiciary. Besides this, it requires cooperation and collaboration between private stakeholders, rural stakeholders, not-for-profit impact organisations and local public bodies. For this reason, Dasra has analysed 120 organisations with the help of 30 experts. Of the 120 organisations, 67 emerged in the 1990s and 2000s. This increase was due to policy changes, another indication of how better governance improves social indicators of development. One of these milestones were the 73rd and 74th amendments to the Indian Constitution, which legitimised Panchayat Raj and municipal governance, respectively.

Vinod Vyasulu of the Centre for Budget and Policy Studies writes,

“During British colonial rule, India’s traditionally decentralized

governance structure was replaced with a command-and-control system

designed to extract tax and related forms of revenue, with little concern

for service delivery.”

Dasra’s report narrows down four pertinent strategies across sarkaar, samaaj and bazaar: developing media through citizen journalism and independent media; strengthening local governance through policy change, more research to tackle social issues effectively; encouraging woman-centred leadership; and leveraging technology for diversifying solutions, increasing efficiency and designing better development tools.

The World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators lists out six areas of action that determine the quality of governance. In all except one, Regulatory Quality, India has shown decline from 1996 to 2012, showing the picture of a failing democracy. These six indicators are: Voice & Accountability, Political Stability & Violence, Government Effectiveness, Regulatory Quality, Rule of Law and Control of Corruption.

The importance of these quantifiable development metrics is important. For instance, if India improved these indicators by just one standard deviation, it would help decline infant mortality by two-thirds, or raise income by three times in the long run.

The report goes in much detail about the six indicators and organisations excelling at them.

“The extent to which a country’s citizens are able to participate in selecting

their government, as well as freedom of expression, freedom of association,

and a free media.”

Janaagraha was the first non-profit organisation to sign a Memorandum of Understanding with the Election Commission of India to achieve 100 per cent accuracy in voter lists through its ‘Jaagte Raho’ initiative. In the final quarter of 2013-2014, Janaagraha processed one lakh voter forms, which helped register 90,000 new voters in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections in Bangalore.

With the spectre of ‘paid news’ looming Indian journalism, Dasra also highlights the importance of media independence and dominance of ownership in matters of governance. This, especially in the light of the way corporations and governments silence activists who work in the interests of marginalised masses, or, as was the case with Greenpeace activist Priya Pillai, bar them from travelling and have them declared ‘anti-nationals’ on national television. Against this backdrop, Dasra cites long-form journalism magazine The Caravan for consistently producing independent, fair, well-researched and transparent work.

Another organisation lauded in the report is the Jan Janagran Shakti Sangathan. JJSS, a union, works for unorganised workers in Bihar. Its work includes social auditing for employment guarantee schemes and anganwadis. Till date, they’ve audited at least a 100 anganwadis, revealing essential data on corruption and systemic inefficiencies.

“The likelihood that the government will be destabilized or

overthrown by unconstitutional or violent means.”

India may be an under-achieving and faulty democracy, but unlike most of its neighbours, it’s not prone to regular eruptions of mass violence or coups. Still, compared to Bhutan, China and Sri Lanka, our political stability ranks low. Violence, even if not an everyday phenomenon like in Pakistan, is still a reality in the democracy, and it’s mostly on the lines of religious and ethnic differences.

With an increase in right-wing fundamentalism, never has India been this divided in its modern history. Countering issues of stability and violence, hence, is imperative if the nation hopes to improve its governance.

“The quality of public services, the quality of the civil service and

the degree of its independence from political pressures, the

quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the

credibility of the government’s commitment to such policies.”

Almost half a century ago, MK Gandhi said that his idea of village swaraj was one where the village was a “complete republic, independent of its neighbours for its own vital wants, yet interdependent for many others in which dependence is a necessity.”

Dasra reports,

”Madhya Pradesh has made democratic decentralization central to its

development and social service delivery strategy. It has greatly expanded

access to education with a rights approach, linked to an Education

Guarantee Scheme and decentralization of primary education. McCarten

and Vyasulu (2004) find that between 1992/93 and 1998/99, children from

the poorest 40 percent of households, classified by wealth-holding,

achieved a major increase in access to schooling. The probability level for

completing grade 5 increased by 21 percentage points in Madhya Pradesh

versus 5 percentage points nationally. Madhya Pradesh used the district

planning committee provision of the 74th amendment to de-concentrate

government and pass decision-making powers to districts. It also

empowered the gram sabha to carry out the functions of gram panchayats

through numerous committees under the gram swaraj.”

Over the years, numerous acts and schemes have been incorporated into the Constitution to enable government effectiveness in quantitatively improving social indicators in cities and villages: The Tribal Sub-Plan (1974) and Scheduled Castes Sub-Plan (1979) to allow special funds for tribal and schedule castes; the 73rd and 74th amendments to create Panchayats in villages, and Municipal corporations in towns and cities; Panchayats Extension to Scheduled Areas Act (1996) to extend Panchayats to tribal areas; the 2002 Supreme Court ruling that mandates election candidates to file self-sworn affidavits declaring educational, financial and criminal background; Right to Information Act (2005); and Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Gurantee Act (2005), which guarantees 100 days of work per household per year in rural areas. In 2014, the Whistle Blower’s Protection Act was also passed to protect whistleblowers, who expose corruption, from victimisation.

However, to ensure centrally-sponsored schemes (CSSs) succeed, the design and implementation of policy is crucial. Government inefficiency, corruption and lack of research are some of the reasons why welfare and social schemes in India almost never achieve their desired goals. As of 2013-14, according to Dasra, the government has allocated over INR 2,00,000 crores for 156 CSSs. Without proper implementation and transparency, we risk losing a huge amount of this money to poor governance.

Then, there are the issues of urban development. According to the latest report by the Ministry of Urban Development, Indian cities will likely need over INR 50 lakh crore to meet infrastructural needs over the next 20 years. However, revenues generated by urban local bodies during just 2007-2008 were INR 50,000 crore in India – that’s less than 1 per cent of the national GDP. Compared to us, in South Africa, these bodies generate 6 per cent of GDP, and in Brazil, 7 per cent. It’s a distressing reality to behold, considering urban Indians face insurmountable environmental, infrastructural, traffic and sanitation problems.

“The ability of government to formulate and implement sound

policies and regulations that permit and promote private sector

development.”

In 1991, India underwent massive economic liberalisation. The nation was gripped in a financial crisis as its waddled through a cesspool of ineffective government schemes, severe phobia of privatisation and a tangle of regulations. In spite of continued, but slow, liberalisation, India is still amongst the most over-regulated countries in the world (Political and Economic Risk Consultancy). ‘Needless obstacles’ for the sake of bureaucracy or as ‘precautionary measures’ has become a cornerstone of our national identity.

Regulations are an important feature of good governance, but they need to be intelligent and serve their purpose: transparency, accountability and setting reasonable limits. Harish Salve, Senior Advocate for the Supreme Court of India says,

“Labour reform is vital, as is the reform of environmental laws, including the set

of Forest Acts. These have to be adapted to enable India to break the cycle of

poverty, reminding ourselves that in the ultimate analysis, abysmal poverty is

the primary cause of environmental degradation. Although Indians are

respected the world over for their entrepreneurial spirit, the business

environment in India has sapped their energy and demotivated most.”

One organisation working to create “an effective legal framework for an equitably growing and humane India” is the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. Recently, Vidhi launched a Briefing Book for the new government. In it, it identified 25 reforms to usher better governance covering four major areas: renewal of basic institutions; deregulation of over-regulated sectors; updating laws and creating legal frameworks to deal with new challenges; reassert itself as a proper constitutional democracy.

“The extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the

rules of society, and in particular the quality of contract

enforcement, property rights, police and courts, as well as the

likelihood of crime and violence.”

If the 2012 Nirbhaya case, and the slew of sexual assault and rape cases that followed it, taught us that the police, politicians and practitioners of law had a shockingly unconstitutional view of crimes against women, Dimapur taught us that Indian civilians aren’t far behind the authorities they relish criticising.

A fair, just and democratic society cannot exist without the proper implementation of laws and rights enshrined in the Constitution. The very basis of a democracy lies in the protection of the weak against the strong. India seems to have failed in providing its citizens these basic protections. In the 2014 World Justice Project Rule of Law Index 2014, India ranked 66 overall and 95 on ‘order and security’ of 99 countries. It’s not surprising that for every 100,000 Indians, India provides only 130 police officers, who themselves are starved of resources required to enforce law and order (besides being deeply politicised).

Even in matters of business, India fairs poorly. In World Bank’s 2014 Doing Business report, we ranked 186 among 189 countries on ‘enforcing contracts.’ If that isn’t astounding, Justice VV Rao says, “The Indian judiciary would take 320 years to clear the backlog of 31.28 million cases pending in various courts, including the High Courts, in the country.”

Little can be said of these negative developments when in 2013, affidavit analysis of Members of Parliament (MPs) and Legislative Assemblies (MLAs) revealed more than 30 per cent (more than 1,000 of 4,807 sitting MPs and MLAs) had criminal charges registered against them. In the 2012 Assembly, Manipur was the only state whose MLAs had no declared criminal cases. And in the 2009 Jharkhand Assembly had an impressive 74 per cent of elected representatives with declared criminal cases against them.

In an increasingly lawless atmosphere, to help citizens access justice, Human Rights Law Network (HRLN) was founded in 1989. Socio-economic barriers is the major reason for why millions of Indians find it difficult to redress grievances. HRLN has provided thousands access to the Indian justice system, including training in human rights law, legal reform, monitoring and investigation into human rights abuse and ‘know-your-rights publications’. Their valuable work ensures that roadblocks to legal recourse are broken down.

“Capturing perceptions of the extent to which public power is

exercised for private gain, including both petty and grand forms

of corruption, as well as “capture” of the state by elites and private

Interests.”

Virtually all of India’s institutions are corrupt, private or public. According to Transparency International, we’re the 85th (of 175) most corrupt country in the world. The details of the Corruption Perception Index report are even more damning. The research showed 86 per cent of political parties, 75 per cent of police, 65 per cent of public officials/civil servants and 65 per cent of parliament/legislature were perceived to be corrupt or extremely corrupt. Ernst & Young and FICCI declared India lost INR 364 billion in corruption between October 2011-September 2012, excluding the 2G, Commonwealth Games and mining scams.

Corruption is a drain on Indian resources. To tackle this, various organisations have cropped across the country.

Ipaidabribe.com is a stellar organisation working to put a number on corruption in India. Created by Janaagraha, it allows citizens to report bribes (when, where, by whom and the amount), which it archives and shares with media and government agencies. Their latest count shows 39,300 bribes solicited across 864 cities worth INR 252.34 crores. Of these, 20,960 bribes were paid and only 2,661 were challenged.

So how do we even start with dealing with a problem of gargantuan proportions? The reality is that the change from bad to good to great governance will take decades to achieve. An entire generation or two may never see the ultimate fruit of these changes. But change has to begin somewhere.

Dasra broadly discuses the stories of impact, the means of creating and measuring impact to make governance efficient. The most important of these is building awareness amongst citizens and mobilising them. We cannot expect the polity and police of the nation to be the only undertakers of this project. The defining feature of democracy is an informed and proactive citizenry. Unless billions of Indians do their part as stakeholders, India will never see true progress. Knowledge creation and sharing are equally important. Creating technological platforms to efficiently address issues, gathering hard evidence to help develop strategies, facilitating independent and inclusive journalism, strengthening local bodies, encouraging public engagement and facilitating platforms for multi-stakeholder engagement are the most crucial interventions to improving India’s social indicators.

The Dasra report further highlights all the organisations working in this capacity like Action Research in Community Health and Development (Vadodara, Gujarat) and Liberty Institute (New Delhi), which mobilise tribal groups to claim entitlements guaranteed under the Forest Rights Act (2008). The Bangalore Political Action Committee (B.PAC) has its own Civic Leadership Incubator Program, developed along with Takshashila Institution, to train citizens to enter electoral politics at the local level. In Patna, Bihar, IDinsight evaluates government programmes to identify inefficiencies, implementation problems, recommend solutions and improve schemes. Centre for Youth and Social Development in Bhubaneswar, Orissa works on budget and policy analysis to “demystify allocations and the use of funds across government programmes and schemes.” Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative in New Delhi works to make policing a public issue. They helped enact The Kerala Police Act (2011), where 240 of 790 suggested amendments were passed in the Kerala Legislative Assembly. The Ahmedabad Urban Management Centre trains Gujarati municipalities to track water, sanitation and health services on the internet. Janaagraha, eGovernment Foundation and Gram Vaani also work to train citizens to use technology as a platform to track and improve governance. Gurgaon-based Charkha Development and Communication Network is an independent media outlet that focuses entirely on marginalised communities in remote locations and conflict regions like Jammu & Kashmir. IndiaSpend (Mumbai) focuses on public interest issues and fact-checking, whereas, Khabar Lahariya is a weekly newspaper run by rural women journalists in remote areas of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. It’s readership is close to 120,000. In Bhubaneswar, Orissa, The Regional Centre for Development Cooperation (RCDC) and PRS Legislative Research in New Delhi provides government officials access to the latest knowledge, evidence and research to address the needs of the citizenry. RCDC works specifically for panchayats, and has covered over 1,000 villages across 15 districts in Orissa till date. The Hunger Project, based in New Delhi, works to strengthen female leadership in panchayats and Society for Participatory Research in Asia (PRIA), also in Delhi, assists Panchayati Raj Institutions and Urban Local Bodies. It runs pre-election political awareness campaigns on urban governance and poverty across India to ensure these issues become genuine parts of election manifestos of political parties.

Dasra optimistically notes, “India is poised to achieve both, economic growth and human development, with better alignment between the three key stakeholders: civil society, the private sector and the government.”

For this to happen, all of India’s stakeholders – citizens, government, businesses, judiciary, law enforcement, non-profit organisations, media and academia – need to constructively collaborate. The country also needs greater avenues and resources to improve funding. It requires pouring capital into initiatives currently working to better governance, building institutions and improving CSSs. And most importantly, India’s stakeholders need to lead the change.

India’s story is yet to be written, and it’ll take the right kind of people to write the right kind of story. As Gandhi said, “A small body of determined spirits fired by an unquenchable faith in their mission can alter the course of history.”