‘I believe the world is waiting for us with open arms’: The hacker who became a shepherd to protect India’s one true luxury product

A near death experience

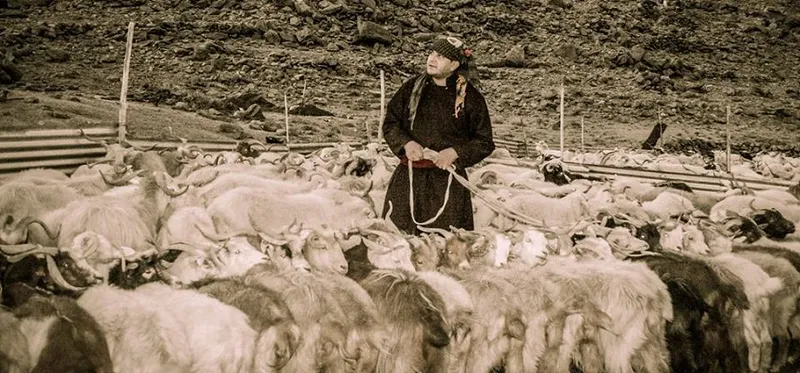

Before he implemented his entrepreneurial solutions, Babar became a shepherd to empathise with the hardships of the community he had vowed to protect. And he almost lost his life in the process. “I got to know that a flock of Pashmina goats was attacked by snow leopards in a village in the outskirts of Leh. This was in the late afternoon and the spot of the incident was about 60–70 kilometres from where I was. Once I reached the spot, it was about a 1.5 mile hike to the place of the attack. As it was getting dark I started to run with only a Swiss knife in my pocket to ward off the leopard. But my weapon of choice was not the biggest blunder of my life. Running at 14,000 ft. was. Soon I started gasping and fell down unconscious.”

The only reason Babar survived is because the shepherds came to his rescue. They lost their flock that day, but saved him from certain death. When he woke up the next day in a Delhi hospital, his resolve to resuscitate the livelihood of the Pashmina shepherds strengthened manifold.

Of the finest fabric known to man

When asked how the idea of setting up his startup, KashmirInk, came about, Babar Afzal is earnest in his answer: “It comes from a journey that is intertwined with different threads. Of the community that has protected the Pashmina goat from centuries. Of a textile so pure that it rests atop everything the world calls luxury. Of a place that is being hit by the severe impact of climate change. Of a state that is known mostly for disturbances and terrorism. It’s about my own journey of quitting a corporate career and taking on a mission to guard the roots of the eco-system and protect the perfection that is Pashmina. And in the process give back as much to the community that has selflessly given us the finest fabric known to man.

The word ‘Pashmina’ comes from the Persian term ‘pashm’ meaning wool. The real Pashmina wool comes from the Changthangi goats of the Himalayas. The goats are cultured in a cold weather that has lured them to develop a protective skin and wool for survival.

The idea came from the need to find an economic solution for the communities that are linked to the Pashmina Industry in India – the country’s original and perhaps the only true luxury product.”

On giving up a Silicon Valley lifestyle to become a shepherd

Babar’s background as a hacker had him earning between 18–25 thousand USD per month in his capacity as an information security consultant. “There was a lot of free travel and stays that was a part of my job profile. I believe I was lucky mostly because there were not many information security consultants and events like 9/11 had created a large level of threat perception globally. Every information security consultant was having the time of their life at that time,” he adds.

The native Kashmiri had left his home state early on to create a better life for himself away from the conflicted zone. And he had been wildly successful. “Before I opted to become an activist and a shepherd, I worked with organisations like McKinsey in India, USA, UK, and Middle East as a technology analyst, business consultant, and a hacker. I hold over 25 High End International Business and Computer Certifications including a PMP Certificate from PMI (USA),” he says.

His exorbitant salary and Silicon Valley lifestyle put him at the top tier of India’s wealthy elite. But in a classic example of how success without meaning is not rewarding, he gave it all up to dedicate himself to a cause he believes in: preserving the Pashmina ecosystem of Kashmir.

Babar says, “When my journey started in 2009, I could not have had a more ostrich outlook to the pathetic circumstances in the valley.” But now he lives that reality every day, asserting that climate change is a far more deadly threat than terrorism in Jammu and Kashmir.

Climate change worse than terrorism

In 2009 a severe drought almost dried up the Tso Kar Lake in Changthang. In 2010 flash floods wreaked havoc with in the region. In 2012 drought and snow led to death of 25,000 Pashmina goats in Changthang. In 2014 the floods devastated Kashmir, leaving the state disconnected with the rest of the country. There are many factors which have directly and indirectly put pressure of the community that is linked to Pashmina for their livelihoods. These include the political uncertainty, competition from machine looms, impact of climate change in Himalayas, fake Pashmina fibre which has taken over the pure Pashmina, no reasonable wages for the workers, reduction in the number of shepherds, reducing population of goats, competition from China, etc.

Kashmir, Cashmere and Pashmina

India’s tryst with Pashmina is a tale for the ages, one Babar loves to recite: “In the late 14th century, the poet and scholar Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani introduced Himalayan goat’s wool to Kashmir, where the word ‘cashmere’ has come from. Hamadani helped develop a weaving industry in Kashmir. The ruler of Kashmir, Zain-ul-Abidin, also had an important role to play – he introduced weavers with more advanced techniques from Turkestan.

It was Napoleon Bonaparte’s 18th century campaign in Egypt that brought Pashmina to Paris. The scarves reached Western Europe following the 1799–1802 French campaign in Egypt. The general in chief sent one back to Paris and its popularity put plans in motion for a French pashmina industry. Napoleon’s wife, the Empress Josephine, began wearing pashmina-style shoulder shawls, sealing their reputation as the height of fashion amongst the upper class. In particular, they would wear scarves with elaborate patterns for significant political and religious events.

In the present time, Pashmina shawls have become a permanent luxury fashion trend as these can be adorned with almost any outfit. Their soft feel gives comfort and a sophisticated look to the wearer.”

But while a well woven Pashmina shawl can fetch up to $200,000 in the boutiques of Milan and Paris, the impoverished shepherds who raise the Pashmina goats and the craftsmen and women who spend months producing a single shawl brave the extreme climatic conditions of their region in pathetic poverty. Exploited by middle men, they have no knowledge of what is the true worth of their craft. Every time a disaster strikes the valley, which as discussed above is alarmingly often, their provisions are wiped out and the battle for survival begins anew.

When Babar entered the scene, he saw the people linked with the Pashmina ecosystem across the Himalayan belt (Ladakh, Basohli, and Kashmir) rapidly decreasing. He says, “This community of nomads and shepherds is the only one physically acclimatised to survive the harsh climatic conditions above 18,000 ft. and temperatures lower than -30 degrees to preserve the rare and the magnificent Pashmina goats that provides this luxury fabric to the world.” He hopes that by enabling the industry to make economic sense for them will enable them to sustain themselves in this unique profession and harsh terrain. He says, “I believe that I am responsible for my community and this beautiful and magnificent species – the Pashmina goat. All I know is that the people I am working for is not capable of fighting this battle on their own and if I didn’t act now it will be too late.”

50,000 shepherds, 3,00,000 craftsmen, and 2,00,000 Pashmina goats

The Pashmina Goat Project, working under the aegis of KashmirInk, has a three pronged approach to tackle the situation. Babar explains, “The core idea of this project is to fight for justice in the Pashmina ecosystem and enhance the lives of over 50,000 shepherds, over 3,00,000 craftsmen and women and over 2,00,000 Pashmina goats. First on the priority list is the preservation of the Pashmina goats. Second, raise awareness about fake Pashmina that is destroying the industry. Third, the creation of a retail fair trade platform for Pashmina Industry that would represent over 3,00,000 strong community of shepherds, weavers, and craftsmen linked with the ecosystem.”

Cut out the middlemen

Cutting the middlemen and putting the community in touch with the buyers, who come in from across the world to source pure Pashmina, is a sure-fire way to get started with the impact. Babar agrees, saying, “We are helping them participate in auctions and sell directly to the bidders that offer the highest price. We are creating global awareness in over 100 countries about the purity of Pashmina and how to responsibly purchase Pashmina that will enhance the lives of millions. We are linking the shepherds, nomads, and weavers directly with the luxury and fashion industry across world so that they get their due share of the process.”

Babar says that he is the only Pashmina activist that he knows of, in the world. This fact has made him a popular target in his state. “It goes without saying that the biggest opposition is coming from the Pashmina traders in the region. There has been a great organised campaign against me carried out by many industry stake holders who want me to stop everything that I do. In an industry which is heavy on cash transactions and is controlled by heavy weights, the potential impact of my work poses the greatest threat to the middlemen. I have taken head on many fake pashmina traders with legal notices and suits and the fights have become very aggressive from all sides.”

He is encouraged by the valuable support he has received. “I have been lucky that I have been able to garner strong support from the CM and governor of Jammu and Kashmir, the VP and President of India. This has created a big deterrent from those elements who want to disrupt our positive work in bringing in positive change for the community on the ground.”

Other threats

The middlemen pose a sinister, but hardly the biggest, threat to the fragile industry. To counter India’s hand woven Pashmina products, China floods the market with Pashmina woven in machine and power looms. Currently, India’s Pashmina production stands at less than one per cent to China’s 70 per cent domination of the global market. Babar rues, “Our Pashmina is thinner than that of China. Plus the craftsmanship of Kashmir has no comparison globally. It takes over one to seven years to make a highly intricate Pashmina shawl with intricate Sozni work. The more competition this craft faces from the machines and power looms, the rarer it becomes. This automatically pushes the prices because of its unavailability.”

He is envisioning leveraging the power of technology to drastically improve the quality of life of the shepherds. “I have designed an application architecture for the nomads which will empower them in the higher reaches of Himalayas to bid for their wool when it is ready. They would get mobile alerts of weather, prices, auctions, medical emergencies, etc. This would connect them not only with their families but also globally with buyers. I am discussing this development project with a few people at IIT to commence work. Then there is a plan to integrate the weavers and craftsmen on a platform which will give them design intelligence from international markets, thus enabling them to make products that are marketable at a high price.”

Salvation

The journey has been immensely hard, but Babar’s efforts are paying off. Kashmir Ink was bootstrapped from his personal savings, but it is getting great interest from Angel investors who want to speed up the startup’s expansion plans. “We are at the advance stage of discussions with a few investors,” he shares. His cause has also attracted some mind blowing talent for Kashmir Ink’s soon to be debuted management team. “The team would comprise a former creative head of Facebook, an investment banker from UK, an international journalist and communications specialist, a Harvard alumnus and business strategist, and a luxury retail expert.”

Kashmir Ink has secured orders over USD one million. Its signature Pashmina shawls are selling at $200,000. Babar plans to invest seven per cent of the sale of each product to be invested back into the community. “This is in place of the marketing and advertising spend. This is one of the key conditions from our end,” Babar affirms.

This condition is directly tied to Kashmir Ink’s plans of scaling up. “We are looking for retail partners across India and over 20 countries. These partners would be forward thinking entrepreneurs who are excited to be a part of the luxury and fashion retail industry. We have worked out a simple format of association at this stage. We are supplying purest Pashmina to our partners against a security deposit and our share of profits come after the sale happens. Anyone who would like to partner in a particular territory can contact us. Each product sold by our partners would carry a three tier authentication certificate for purity and all the pashmina sold will be cancer free.”

The future

Babar radiates positivity at the question of his startup’s future. “I believe that the world is waiting for us with open arms. There has not been a single attempt like this anywhere. Pashmina has been a part of the personal apparel collection of Kings and Queens globally, passed on from one generation to another. We have a product which is the root of true luxury, fashion, and heritage. We would be retailing across all the luxury retail destinations in the world.”

Step up

His attitude towards entrepreneurship is fuelled by Utopian ideas. But he scoffs at the cynicism the term evokes and his advice to likeminded people is straightforward. “Entrepreneurship is about solving problems and this needs young people to take big steps. So step up and participate.”