How social entrepreneurs can use lean startup principles for better impact

The lean startup approach, which is being used with increasing zeal and rigour by startups and corporates, is now being applied to the social enterprise sector as well.

The lean approach offers practical tips and creative organisational mindsets for rapid learning and prototyping, according to Michel Gelobter, in his new book, ‘Lean Startups for Social Change: The Revolutionary Path to Big Impact.’

Michel is the founder of green energy solutions firm Cooler Solutions, and has been a climate strategist for over 25 years. He was co-founder of BuildingEnergy.com and Chief Green Officer of Hara Software, a Kleiner-Perkins portfolio company. Michel helped form the Climate Justice Corps to train youth in climate activism, and founded the Environmental Policy Program at Columbia University and the Environment and Energy Track at Singularity University.

The book’s foreword is by Steve Blank, one of the pioneers of the customer development process. “A thriving culture of lean within the impact entrepreneur and founder communities could accelerate social change by removing taboos around experimentation and failure,” adds Christie George, director of New Media Venture (NMV), in another introductory note to the book. NMV’s digital news startup Upworthy famously tests 25 different headlines for each article, before finding out which draws the most audience.

The early approach to many social enterprises was ‘Plan, Fund, Do.’ Instead, the lean startup mantra of ‘Build, Measure, Learn’ encourages founders to conduct small experiments, quickly get real-world feedback on them, and use that data to expand only on what works.

Successful exemplars are WorldReader (which moved from print book donation in Africa to e-readers), as compared to other struggling initiatives like One Laptop Per Child (rugged laptops which have been superseded in many markets by mobiles).

Michel illustrates these principles in his 215-page book via four detailed case studies from the US: National Museum of the American Indian (cultural heritage), New York City Toilet Bowl Retrofit Program (reduction in water consumption), Catalogue Choice (reduction of junk mail in paper catalogue products), and Smarter, Cleaner, Stronger (environmental campaign).

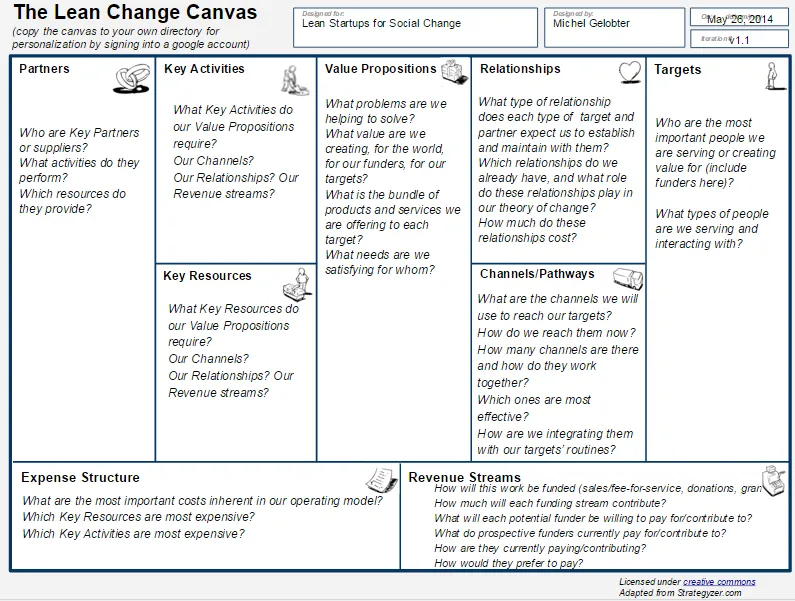

These organisations have leveraged the three core lean principles: (i) fail fast, learn fast (ii) agile development (build – MVP – measure – data – learn – pivot – rebuild), and (iii) efficient innovation via clear and aligned metrics. The organisations have also grown from early discovery, validation and creation to institutionalisation (with processes and operational models). The author provides a range of useful online tools in this regard, such as Lean Change Canvas.

“Making change is different from making money, and startups in the social sector have to worry about far more than revenue,” explains Michel. They are also dependent on the agendas and workflow requirements of their donors, grant agencies and contributors in different ways. Social entrepreneurs are looking at larger impact areas like consumer behaviour change, cultural preservation, public health benefits, and human rights. Many of these also have finite windows for impact, otherwise there is a lost ‘opportunity cost.’

For each of the four case study organisations, the author steps us through their navigation of the Lean Change Canvas. Here are my takeaways and tips from the lean method applied to social entrepreneurs.

- Discovery

In the ‘early guesses’ mode, use the one-page format of the canvas to quickly write down early assumptions of your domains. The different boxes will vary in their importance along the startup journey. Start with brief descriptions before full immersion. Separate out consumer segments (direct, indirect), and problems from needs.

Map the usage and decision-making cycles, while identifying influencers, channels and referrals. Fill out the customer relationship funnel (get – keep – grow). List the physical, intellectual, human and financial resources needed.

In the ‘get set’ and ‘get out’ modes, more research has to be done, fortified by direct communication and interviews with experts, peers and target customers. Online MVP tests can be done via online surveys, videos and blogposts. This can determine customer level of interest, intensity of the problem, willingness to pay for a solution, and enthusiasm to do referrals.

Based on this feedback, the social entrepreneur can decide to pivot, reframe the situation and proceed (exiting and moving on to another cause is also an option). Typical types of pivots are zoom in/out, change customer segment or addressed need, change channel, or resort to new funder.

- Validation

Now that product-market fit has been reached, two sequential loops have to be initiated – getting customers, and keeping them while intensifying engagement (get + keep and grow). More marketing initiatives will be needed to ‘prime the pump,’ via campaigns and growth hacking tools. Metrics can be unearthed via A/B testing batches for overall impact.

Founders should go deep before trying to get big, and use innovation accounting to track progress. Numbers and anecdotes both yield useful insights on customer awareness, interest and activation. Churn rates, virality and paid acquisition costs are important metrics in this phase.

- Creation

Scaling calls for organisational creation. Michel identifies three functional ways in which NGOs drive change: via products/services, laws/policies, or norms/behaviours. These in turn involve creating a new market, re-segmenting an existing market, or fortifying an existing market.

While the startup phase was about development, the institutionalisation phase is about formalising vision and mission, and delivering these via processes. People, job roles and organisational culture are key drivers in this regard for mission clarity and commitment. The founders will have to gear up to move the customer base from beyond early adopters to the majority.

For example, the National Museum of the American Indian aimed to deliver a national collection of cultural artifacts, for researchers and the public. It developed a membership scheme, and leveraged political connections. The New York City Toilet Bowl Retrofit Programme offered citizens water saving options via subsidised toilet bowls. Plumber unions were engaged along with advocacy and educational campaigns, drawing on water conservation budgets from the government.

Catalog Choice gave consumers a voice in reducing paper waste by specifying only those print catalogues they would like to receive from catalogue vendors. It roped in partners such as the postal service and direct marketing associations.

Through 15 tables and charts, Michel compellingly shows how these organisations navigated the Lean Change Canvas throughout their journey. These tables include categorisation of interview responses by emotional intensity, attitudinal roadblocks among customers, positioning statements, mission statements, types of functional activity, impact metrics, and goal targets.

The book ends with some emerging trends in lean social space. Many foundations have innovation funds especially dedicated to rapid prototyped social change. There are even equivalents of FailCon in the social entrepreneur space. Governments are launching their own incubators and startup initiatives. Micro-grants and crowdfunding are encouraging more experimentation and smaller experiments.

“The lean startup for social change is a radical new way to listen to people. It is also a force for innovative democratisation,” sums up Michel.