HBO's Silicon Valley may feature a tech company, but the drama is mostly legal

Silicon Valley, which returns for a third season on April 24, is a satire about the building of a tech company in the startup capital of the world. It has all the elements you expect to see in such a show: socially awkward software engineers, scheming billionaires, lofty promises of changing the world and tussles over term sheets. But what stands out is the fact that much of the drama in the show comes from legal troubles. And why not? Tech entrepreneurs are notorious for underestimating legal obstacles. For a TV show, such drama is good fodder, but, as a startup entrepreneur, why waste time on anything avoidable? So here's a look at the legal troubles featured in Silicon Valley and how legal precautions might have prevented them.

Do your due diligence

In the show, Richard Hendricks, who is the main character, develops a compression software that generates a lot of interest from his CEO in the fictional company Hooli and a powerful venture capitalist. The name they set for the company is Pied Piper, in whose name funding is ultimately given. They print T-shirts with the name, too. But when they attempt to register a company in the name of Pied Piper, they realise there's already a company with the name (Pied Piper Sprinklers), which they have also trademarked. Ultimately, Richard makes the long drive over to Pied Piper Sprinklers and manages to get the name for $1,000 or 1/200th of the initial funding his company received. He got it, alright, but things could've been much simpler if he'd just done his due diligence.

Legal learning:

Due diligence is a much broader term and is continuous while running a business. Before you sign anything, approach a VC, hire an employee, whatever, you perform your checks. Make this a habit and you'll ensure you won't waste anyone's time. Decide to ignore it and you may end up wasting a lot of time and money just clearing up the mess.

Keep your secrets safe

Any hot company will have suitors, not all of them with the right intentions. In the show, Richard, in the quest for funding, ends up being tricked into revealing much of the algorithm, as the 'VCs' he is meeting want to understand what he has built before investing. Ultimately, the 'VCs' turn out to be a competitor simply looking to steal the Pied Piper architecture. They ultimately succeed at engineering the product and cause the team at Pied Piper a world of trouble, if you remember.

Legal learning: Now, it might not be normal to ask a VC to sign a non-disclosure agreement, but when anyone asks you to reveal product secrets, you absolutely have to ensure you have legal recourse in case they decide to use your product.

Intellectual property means everything

In the tech world, intellectual property means everything. In the show, Richard builds Pied Piper largely using the laptop given to him by his then employer Hooli, a corporation as large as Google or Facebook. When Hooli decides to sue Pied Piper for theft of intellectual property, as Richards' employment contract stated that all his work at Hooli is the property of his employer, the company is only saved by an illegal non-compete clause that renders the entire contract void. That's a lucky break. But, if you're currently working on something on the side while being employed full-time, this is something you should pay attention to.

Legal learning: The IP for your software is the most valuable asset your company will create. You need to do everything you can to ensure it stays yours. This means completely separating it from your employer, keeping the code secret, and copyrighting it if you have to. If your software also has hardware attached to it (say, VR or Blackberry), you could also consider a patent.

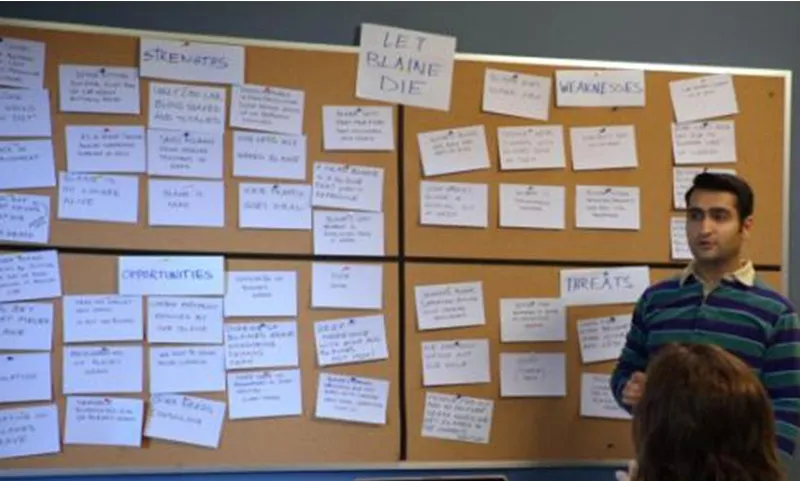

Ensure the company is yours

The equity in your company is limited. Never make a mistake by giving it away cheaply. But a lot of founders end up doing so. In Silicon Valley, Richard unnecessarily gives away two board seats to an investor called Russ Hanneman, even though his commitment to the company is clearly suspect. Giving two out of five seats away for 'dumb money' is clearly a bad move, particularly when the other investor buys out the seats for a majority on the board and votes you out as CEO. Who's dumb now?

Legal learning: You may be founder and CEO, but good businessmen make a habit out of listening to experts around them and readily admit their shortcomings. If you're dealing with VCs and investors before you know a term sheet from a shareholders' agreement, you better ensure you're talking to a lawyer before making any move, or you may soon end up losing more than you expected to.