Has the rise of tech entrepreneurship in India exposed our greed?

After $14 billion dollars that gushed into the Indian startup ecosystem in 2014 and 2015, the year 2016 has been plagued by drying coffers, floundering business models, mass firings, premature business demises and a lot of hand-wringing on the part of both investors and founders.

Were the events at TinyOwl, Housing, or Jabong driven by ineptitude or greed? Did the eternal question “funding mila kya?” trigger perverse incentives and hubris? Let’s explore.

Flashback

For long forty-odd years, making money was the preserve of the business class. Business aspirations were looked upon with suspicion, and Nehruvian socialism, along with a stringent Licence Raj, made sure that India kept her entrepreneurs at bay.

While the 1991 liberalisation was the big catalyst, the seeds of change in narrative and how wealth generation would be viewed by Indian middle class were sowed as far back as 1974.

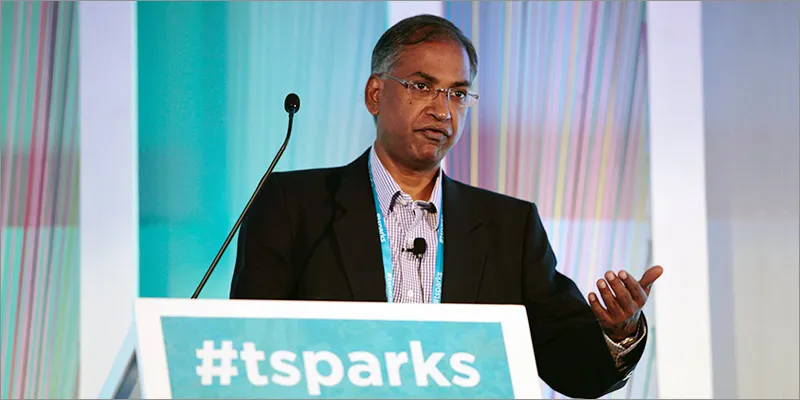

That was the year when a 28-year-old NR Narayana Murthy had a brush with the ugly side of the Iron Curtain, when an innocent conversation in French on a train in Bulgaria was misinterpreted as criticism of the regime. This led to over 72 hours of detention without food, water, and being locked up on a freight train to Istanbul.

Recounting the events to students at Stern School of Business, New York University, in its 2007 pre-commencement lecture, Murthy said,

“The journey to Istanbul was lonely, and I was starving. This long, lonely, cold journey forced me to deeply rethink my convictions about Communism. After being hungry for 108 hours, I was purged of any last vestiges of affinity for the Left. I concluded that entrepreneurship, resulting in large-scale job creation, was the only viable mechanism for eradicating poverty in societies.”

In India, we are all familiar with this story, and how this transformation in political belief led NRN to establish Infosys in 1981. For those of us reporting from Bengaluru in the mid-nineties, no conversation with NRN was complete without the retelling of the hitchhiking story.

In a 2010 interview in Forbes, former P&G CEO Gurcharan Das, quite suitably noted, “After 1991, for the first time business is acquiring respect in the society. Industrial revolution began in Europe and the US 200 years back. Their businesses are in second, third generation. And you see the philanthropic side to it with people like Bill Gates now. It’s a common saying — the first generation makes money, the second generation wants prestige and power, and it is the third generation that wants art, culture, status, and aspires for respect.”

Funding mania – losing the plot

The journey from 1991 to 2016 was paved by many entrepreneurial and business successes, most notably the startup action in the last few years. Technology became a great leveler in post-liberalisation India. Who would have thought your bedroom could double up as your boardroom? A laptop and WiFi connection were all that were required to conduct your business from your garage or a coffee shop. Flipkart, the Infosys of its time, became the vanguard of these new tech-led businesses.

However, somewhere the fledgling Indian startup world is in peril of losing the plot. VC money is being poured into flashy billboards, celebrity endorsements on television, and jazzy offices instead of updating technology, restructuring and regrouping products or services.

Entrepreneur and early-stage investor Kashyap Deorah, who covers these and many more aspects of tech entrepreneurship in his book, The Golden Tap: The Inside Story of Hyper Funded Indian Startups, says,

“I can argue that greed is good and someone else may argue it is not. However, most will agree that integrity should remain intact. Integrity, of course, is subjective especially in the absence of swiftly enforceable laws like in India.”

Just like the US saw integrity get pushed to the limits and was put to test during the dot com bubble of 1999-2000, India saw that happen in the e-commerce ‘bubble’ of 2014-15, he feels. “From the inside, it seemed like entrepreneurs, angels, and VCs alike doubled down on getting returns on investment by selling their shares to global late-stage funds through momentum rather than building a business that gets returns to all shareholders through value,” he tells me.

Kashyap attributes this to the trader DNA of Indians. The US is a consumption economy. China is a production economy, while India, he says, is a trade economy.

Hitting below the belt, K Vaitheeswaran, a pioneer in the startup space, says that the only goal for entrepreneurs today seems to be to raise money, and that in the last five-seven years, most entrepreneurs successfully persuaded investors to part with their money.

When I caught up with him, he expressed grave reservations. “It is all about 'have I raised more money than the other person'. And through that comes the sense of entitlement. What they do not realise is that funding was the result of the cycle that happened. It is not because their business model was sustainable. Now that $100 million have been spent and no more money is coming in, many are struggling.”

Describing this phenomenon as “rising tide lifts all boats,” Sanjay Anandaram, mentor to startups, says entrepreneurs need to move away from the funding hype and instead focus on how to build strong organisations and a legacy.

Back to basics for survival

The best place to test the pulse of what’s brewing in the startup world is obviously a startup event. At a recent one I attended, three facts emerged: Funding is like being on steroids. Discounts do not build brands. Stick to roti, kapda, aur makan; unless your core is 200 percent solid, your business will not do well.

Remarking on the funding noise that is threatening to drown all other conversations, investor Anand Lunia of India Quotient in a recent tweet commented, “Disproportionate, premature funding has caused more damage than lack of funding.”

Anand tells me in an email interaction,

“Today, founders struggle to balance between growth that is bought and growth that is earned. Frankly, most don't even know how to earn growth.”

In his opinion, the early (e-commerce) players took a “discounting route” to acquire customers. This was perhaps essential to educate the customers and create awareness. But due to the excess funding and competition, it was stretched way too far.

The fallouts of this are many. “One, consumer behaviour was permanently altered into thinking that online purchases are better since they offer a substantial discount over offline ones. Two, employees of these startups became almost mercenary. Three, the early employees made no ESOPs and had no steady jobs, so everybody now wants only high salaries. Four, the permanent flow of manpower that seeks challenging roles -- like it does in the US -- has stopped.”

His comments further indict founders, who, he says, had wrong role models and chased only funding rounds in a game of one-upmanship over their peers. He is scathing in his remark,

“Today, ethics of employees, suppliers, and even founders has been damaged due to excessive greed, fuelled by the oversights of investors, and ultimately trust with investors was lost.”

The lesson here is that the time has come to go down to the basics. “It’s like when you make steel, the spine in the steel needs to go through fire once, otherwise, it remains soft and brittle,” remarks Vaitheeswaran, alluding to the trial-by-fire test that separates the men from the boys.

It’s a VUCA world

The ancient text of the Arthashastra, written during the Maurya reign, dwells in great detail on the winning tactics of the leader, in this case, the king.

Ananya Vajpeyi, in an article in Public Books titled, ‘An Ancient Treatise and the Making of Modern India’, writes, “In the latter half of the text [in Arthashastra], we get an overwhelming sense of the importance of surveillance, stratagem, and counter-insurgency to the ruler’s control over his kingdom. People are not who they seem to be; identities are in flux. Enemies and rivals swarm within the kingdom and flourish abroad; the king must be vigilant at all times and trust no one.”

Interestingly, Rajiv Jayaraman, Founder and CEO of Knolskape, points to the somewhat similar VUCA world that business leaders inhabit today.

VUCA is the business acronym that stands for volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity.

“I would say the startup world is as VUCA as you can get,” Rajiv tells me.

Should today’s entrepreneur then take a leaf out of Kautilya’s Arthashastra and look at solutions as if they were in a perpetual state of war? What Rajiv suggests, perhaps, comes close to that scenario. He rates ‘hustle’ highly in his book of must-haves for startup founders. “An entrepreneur is one who has spotted an opportunity that others have not or maybe others have but are unable to move fast enough. Being a nimble and lean startup, she can move faster. Startup leaders have to be clued in to what’s going on around them,” he says.

This ears-to-the-ground approach, according to Rajiv, is what will set an entrepreneur on the path to success. Startups need to look at strategy in a new light. “Strategy is not about power-point presentations. It is about what you will do now to take you from here to there,” says Rajiv.

Humility - ingredient for success

While meeting potential startups to invest, what do investors look for? Popular perception indicates it would be passion and personal drive, creativity and innovation, relevant industry experience, and those who have completed proof-of-concept and have some user or revenue traction.

Abhishek Shanghvi, Co-founder of Indore-based Swan Angel Network, believes that his theories on startups are more balanced than the commonly held attitude of exponential growth at all costs. He shares in an email interview,

“We avoid entrepreneurs who seem too money-minded or have lofty valuation expectations (gap is more than 3x).”

Interestingly, the top differentiator, when all the parameters of what go into the making of a sound entrepreneur are equal, is the quality of humility. That was the overwhelming consensus from people on both sides of the funding table.

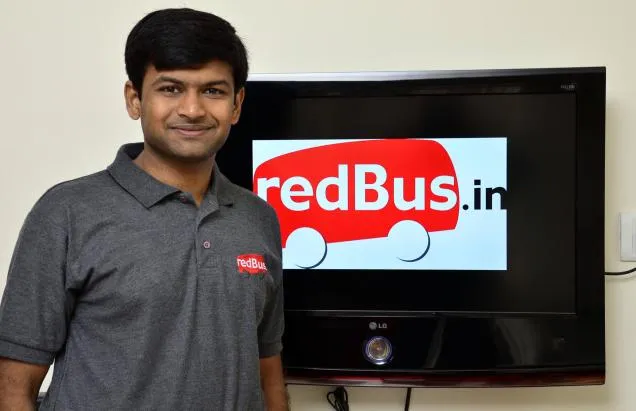

Political correctness stopped many I spoke to from naming who they considered a successful entrepreneur today. But the one name that kept bouncing back was that of Phanindra Sama and his redBus success.

From picking a much-needed local problem, to “pounding the pavement” (as Vaitheeswaran calls doing business the old-fashioned way), to securing a kickass team, and keeping the engine running with a consistent flow of funds, Phani ticked all the boxes.

Instances of Phani and his team’s frugal ways abound in the startup folklore (if one can call it that yet). Even when they had money, they never splurged. They always economised, preferring to travel by bus or train rather than fly. The list is a long one.

For founders looking to raise funding, a good question to answer then would be: Is raising money a means to an end or the end itself?

Kashyap Deorah says it like it is. “When we saw large pocketed funds looking for leaders in specific market spaces with specific vanity metrics, competitive entrepreneurs and VCs started building this to spec. It had to be built fast, by hook or by crook. Most knew this is not sustainable and many of them knew the end game exactly. To me, that was a violation of integrity. As karmic people, we know that we will all have to pay our dues for those lapses.”