When organic farming mainstreams persons with disabilities

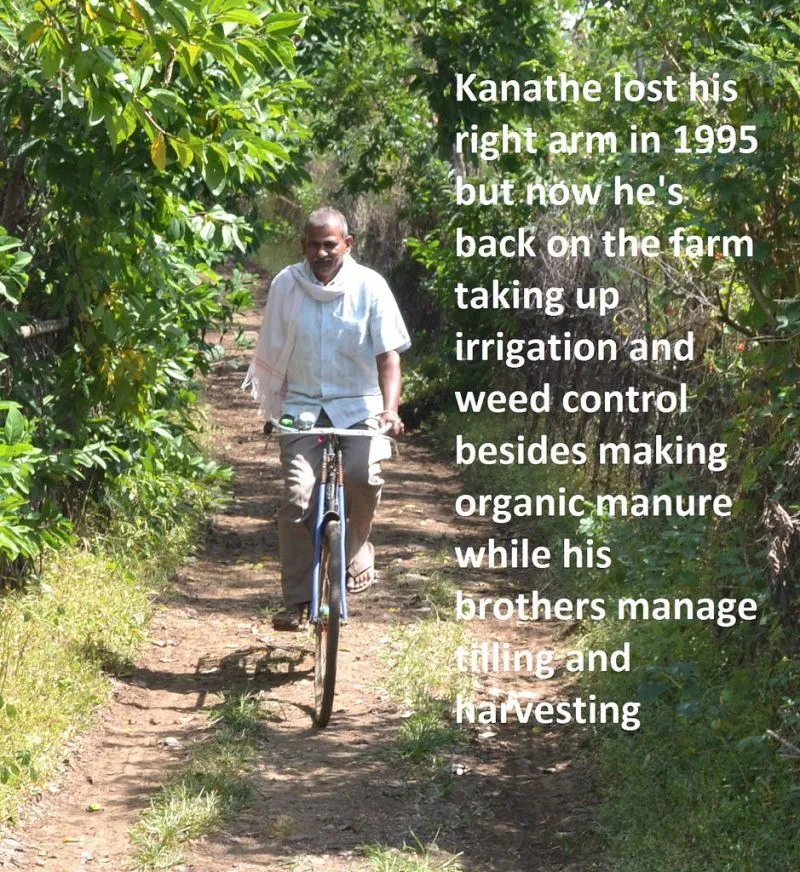

In Madhya Pradesh, a unique experiment with organic farming is mainstreaming persons with disabilities.

A thatched cattle shed marks Omchand Mahatule’s farm which lies on the approach road to Nayagaon village in Betul district of Madhya Pradesh. The 50-year-old comes running from the well clutching lemon grass from which he makes a splendid black tea. Starting off with invectives for his neighbours, the athletic farmer gives a lowdown on the recent tragedies. “Yesterday, somebody stole the bottle gourd which was almost 4 feet long. It would have grown further if the greedy people had not taken it off,” he informs shouting more insults towards neighbours. This was the recent incident of theft.

Mahatule feels it’s his success which is making others jealous. He is famous for reaping a rich harvest of vegetables which grow to great proportions and sell fast at nearby markets. Mahatule has been pursuing organic farming for last two years. “The shift has not only helped increase moisture content in the soil thus requiring less water but also reduced input cost by Rs 35,000,” he claims.

From soyabean, groundnut to pulses and all sorts of vegetables, Mahatule’s field brims with diversity. But all this would not have been possible without his son Rajesh’s commitment to the cause. Though he has no sensation in his body from waist down, the 20 something boy pedals down to the fields on a wheelchair every day to monitor the work. With a master’s degree in sciences, he has a keen eye for nature’s work, preparation of manure and scheduled tending of various crops. “Many people feel a disabled person can’t contribute to farming but there are many ways in which Rajesh has helped the farm income grow,” informs his father.

Every week, Rajesh goes to the local market selling vegetables on his wheelchair. “Our vegetables look and taste better than other sellers and I am the first one to exhaust my entire stock. It’s only after taking to organic that we have been able to cultivate enough vegetables to sell in the markets,” he informs.

The young man has also trained around 17 farmers of his village on preparation of manure, weeding and other natural ways of crop tending. In a way, organic farming has offered Rajesh an outlet to not only be a leader but also a catalyst for improved lives of others.

People with disabilities are often seen as unproductive beings requiring assistance. This perception is starker in rural India where lack of varied work options, good public infrastructure, and assistive devices leave little scope for those with disabilities to realise their potentials.

In such a set up an initiative to propagate an all-inclusive organic farming model is bound to attract disbelief. But Naman Seva Samiti, a non-profit working with disabled persons in the Betul district, is trying to establish a new belief system.

Seeds of mainstreaming

Mahadev Charokar (39) is vision impaired but has got amazing hearing, olfactory and tactical senses. He can differentiate between various denominations of currency notes, can walk up to his farms 1.5 km away, and even lead a bullock-driven plough on fields.

When Naman Seva Samiti decided to introduce organic farming in Betul, he emerged as one of the most dedicated foot soldiers. In his village, Jwara, around 27 farmers have turned to organic thanks to Charokar’s efforts. He not only makes his own organic manure, but also trains other farmers on biodynamic compost making and natural seed treatment.

Making accurate measurements of various components, assessing quality of cow dung and digging compost pits, the man does not inspire awe anymore. The villagers have got so used to his skills and calibre that they see him more as an efficient farmer than a vision impaired man doing something extraordinary, an indication that Charokar’s mainstreaming is complete.

“For me as well as for others my lack of sight is not an impediment anymore. I can speak well which inspires and instils faith in people,” he asserts.

Charokar is a master trainer on organic manure and composting, a profile which takes him to other villages and gets extra income. Now he is planning to open a small shop from where farmers can easily access organic manure.

How organic helps

It was a chance introduction to organic farming that inspired Naman Seva Samiti to promote this concept. Its four-member team attended a workshop on organic farming at Kathgodam, Uttarakhand. They got so enthused by the concept that on return, they started practising it on their individual farms and got good results. Further study of the organic model through exposure visits to other states strengthened the belief that it could be a solution to agrarian, environmental, and health crisis the area had been facing for long.

Betul borders Vidarbha region which is infamous for the highest rate of farmer suicides in India. While the monsoon rain causes erosion of the fertile top earth of the hilly terrain, the soil is a poor keeper of water. Thus the underground water can only be found at great depths of 400-1,000 feet. Rising inputs cost of farming is pushing families into poverty and increasing climatic variability is further aggravating the crisis. “Organic farming is extremely essential in this area since natural manure helps retain soil moisture and stronger stalks and roots of the crop prevent soil erosion. Low input cost and healthier food help deal with poverty and malnutrition, which are also two major reasons for disability,” says Shishir Chaudhary, secretary of Naman Seva Samiti.

Since the organisation was already working on mainstreaming of persons with disability through vocational trainings and convergence with government schemes, any new initiative needed to pass the inclusion test. Thankfully, chemical-free farming encouraged persons with disabilities to get involved as cessation of market resources meant increased human efforts for selection and conservation of quality seeds, preparation of manure, rearing livestock on organic feed, and regular tending of crops.

“Though a regular farmer whined the increased workload, those like Charokar saw the opportunity to prove themselves. Since people with disabilities are most affected by poverty, malnutrition and ecological degradation, involving them in this effort also means we are giving power to those who need it the most,” points out Krishna Kumar, who manages PowerPoint sessions and field trainings for farmers.

Local trainers like Krishna worked on the training programmes to make it comprehensible for those with varied types of disabilities. A new set of smaller and lighter farm tools for those with functional disabilities have also been developed according to individual needs and applications.

How it expands and why

Thanks to all these efforts, currently 165.76 hectare is under organic farming in the area through over 327 farmers. Of these, 81 are women and 161 are persons with disabilities or their family members. There are 74 trainers, mostly persons with disabilities like Charokar, who act as peer educators providing information on preparation of natural compost, pest control, farm maintenance, livestock management, and government schemes.

Each farmer, with maximum of 4 hectares under organic cultivation, is member of one of the 24 farmers’ microfinance groups. These groups are further affiliated to Haldar Krishak Federation, which procures and sells the organic produce in market. An 11-member elected committee looks after functioning of this federation.

For many of the members, it was an opportunity they were waiting for. Yograj Khakra, the current federation president, calls it a personal journey of redemption and hope. His daughter Vaishnavi died last year at age five. She was born with multiple disabilities including cerebral palsy and mental retardation. He is sure it was the food they were growing and consuming which impacted the child.

“I was using very large amount of fertilisers and pesticides on my farm to ensure highest production. The priority I gave to money costed me very dear,” he laments. It’s not difficult to believe him. Several studies and anecdotal narratives have linked pre-natal exposure to pesticides to lower IQ and genetic diseases among children.

Over the years, he has gradually increased the area under organic cultivation to half of his 10 acre land. “It’s not easy to go organic in one go. The loss in production is most evident in the first year which is why farmers expand by one acre every year to cushion the loss in income,” he informs.

Khakra is now producing one of the best wheat and soyabean crop in the area as farmers from nearby villages come over to look at his crop and buy farm-saved seeds. “I sold the soyabean seeds for Rs 6,500 per quintal as compared to the market rate of Rs 6,000,” he says.

Since he is also giving organic feed to his cattle, the quality and quantity of milk has improved as well. “Around 15 families of nearby Athner town take milk from me and though I have increased the rates by almost 50 percent, none of them has dropped off because the quality is much better now,” Khakra points out. He has trained around 15 farmers in his village who are now pursuing organic cultivation. “However, the conversion rate is very low. Many farmers admire my crops but they still spray chemicals because organic farming requires more effort. They prefer convenience by investing more money without acknowledging the adverse impacts,” he explains.

As we talk, a small girl wanders around us chirping in her toddler tongue. “This is my second daughter. She is completely healthy and all credit goes to the chemical-free food we are having now,” Khakra asserts.

The grouping

All federation members are following the standards required to gain formal certification of organic farming. Peer educators regularly monitor and advice on treatment of seeds, selection of border crops to avoid aerial contamination, sanitisation of tools and implements before use, preparation of organic pesticides, and exclusive storage space for the harvest.

Since there is more than one organic farmer in each village, self-regulation is quite effective. Members monitor each other’s practices and report in case of non-compliance to the federation. The review system is very strict and has led to the exclusion of 173 farmers after they were found to be violating the norms.

This group effort is further bolstered through convergence with government schemes. Around 200 farmers linked to the federation availed of the government subsidy for construction of vermicompost pits while 19 farmers got the machines for grading of produce.

Next level for the Haldar Krishak Federation is to crack the market for organic produce. Though several procurement agencies and companies have already shown interests in the crops, the farmers are yet to work out a standard market mechanism which can fetch them the best price.

The way organic farming has been able to deal with issues concerning disability, it testifies the theory that nature is a great leveller. It showers its bounties equally on all.

Disclaimer: This article, authored by Manu Moudgil, was first published in GOI Monitor.