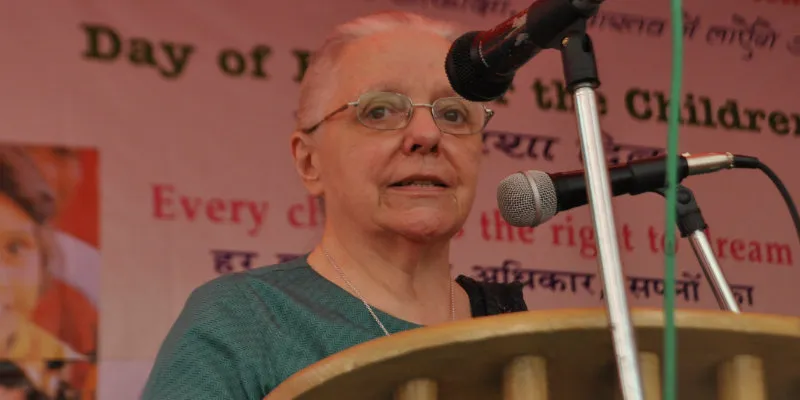

Sister Jeanne Devos is the strong voice of domestic workers in India

Sister Jeanne Devos’ NGO, the National Domestic Workers Movement, advocates the rights and dignity of domestic workers.

In what can be termed a positive move, the Union Government last month considered formulating a National Policy for Domestic Workers that would entitle them to a minimum wage, social security, fair terms of employment and grievance redressal among other things.

If implemented, it would come as a relief to more than 4.2 million (official estimates) people in this largely unorganised sector, many of whom are overworked, underpaid and, in some cases, abused by their employers.

A calling for a higher purpose

Championing the cause of domestic workers in India since the early 80s is Sister Jeanne Devos, the founder of the National Domestic Workers Movement that backs one of the most powerless segments of society.

Sister Jeanne Devos came to India from Belgium in 1963 as a missionary. Hailing from a farmer’s family, she truly believed that everyone should be treated equally, irrespective of class and gender. Influenced by the youth movements in a post-war world, she chose to join a congregation and move to India.

“I don’t know where my love for India came from, but I had a great love for Rabindranath Tagore in my youth and found his work very inspiring. I also loved the ‘mystique’; the yoga and the relationships between people,” she says.

Sister Jeanne started working in a school for the hearing and visually impaired in Chennai.

“From there, I started a students’ movement in the 70s that had volunteers working in refugee camps, cyclone-affected areas, and other places that needed help. I wanted to work with the most-exploited and according to me, there were three kinds – those affected by slavery, ‘house’ workers, and bonded labourers,” she recollects.

Most of these workers lived in dire circumstances and many were also pushed into prostitution. Many were bonded labour and were often pitted against one another because they vied for the same jobs.

The birth of a movement

An incident that happened soon after changed her life forever. “I met a girl, not even 13, who was raped by one of her employers. She became pregnant and was forced to abort the child 600km away, without the knowledge of her parents. This incident moved me and I felt something had to be done,” she says.

Sister Jeanne began working with women and children in Dindigul district of Tamil Nadu and encouraged small groups of domestic workers to come together with the objective of supporting themselves and each other. In 1985, she relocated to Mumbai and assisted with setting up some more domestic workers’ groups. This led to the launch of the National Domestic Workers Movement, which soon moved to 17 states.

“We wanted to be a catalyst for change and not just a charity organisation. It was tough from the beginning because domestic work comes with a stigma of its own. These people have been looked down upon for generations. Domestic workers due to this were under the assumption they were not fit for anything else. That they were made for this and could not do anything else. If they feel they are doing something important, you will see their strength coming to the fore,” she says.

According to her, the three aims of the movement are to work for dignity, rights, and empowerment of workers.

“An important goal is also to empower women and enable them to make decisions for themselves. Based on these aims, we started campaigns against trafficking of women and children, and also endeavoured for a change in public opinion.”

Bringing in visible change

Sister Jeanne played an active role in securing recognition for domestic workers at the national level as workers and the international level by the UN. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) declared domestic work as decent work by adopting Convention 180, which spells out the labour rights of domestic workers.

“Domestic workers were earlier not even called by their names. They did not have a personal identity; the movement has changed that, which is extremely important. People started valuing domestic work, the workers valued themselves and their work. They were like slaves and one of the biggest parts of the movement was breaking the chains of slavery,” says Sister Jeanne.

Children have a right to life

While a number of laws are in place in India to curb child labour, there were more than 10.2 million ‘economically active’ children in the age group of five to 14 years with eight million children were working in rural and two million in urban areas, according to the last Census.

The National Domestic Workers Movement has strived to work towards rescuing underage working children.

“We have to support the fact that all children below the age of 14 should be in school. Employers should by no means employ children of that age. We have movements for the protection of children wherein we have rescued children from child labour. They are fighting for their right to study and it gives them great pride to go to school. They look after not only themselves but also look out for other children in the neighbourhood who are not going to school. Mothers and fathers join the movement as well. We also have homes for children who are victims of trafficking and labour,” informs Sister Jeanne.

Changing mindsets and tackling challenges

Sister Jeanne believes that there has been a change in the way people perceive domestic workers and their work. “Employers have started paying better, workers are being respected and they are conscious of their plight and dignity. But much more needs to be done.”

The biggest challenge has been to change attitudes.

“Workers have organised themselves into unions in order to get this approval from people and not be disrespected. It has been a challenge to ensure domestic workers are treated the same way as others and are given their rights, like sick leave, etc,” she says.

Deriving strength from faith

“My future plans and dreams are solely the ratification of the ILO law. That legislation is extremely important because it is not only the members of the movement but all the domestic workers who need to have a little protection. Everybody who is born in India has the right to go to school and educated. Even groups of domestic workers who are HIV-infected should get sufficient care. The main thing, however, is to ensure legal protection of workers and children,” says Sister Jeanne.

She says that she gets her strength from faith and from the different groups under the movement, especially children’s and workers’ groups.

“When you see the level of pride and strength in them, you cannot let them down. Once you have started a journey, you cannot turn back. For me, this is a part of a journey to set people free, as opposed to merely just giving them some food and stopping there. We have to give them their dignity and the ability to live a fuller life.”

![[Funding alert] Edtech startup Codeyoung raises seed round from Guild Capital](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/b87effd06a6611e9ad333f8a4777438f/Image4dwi-1601370032995.jpg?mode=crop&crop=faces&ar=1%3A1&format=auto&w=1920&q=75)