What will it take to bring back the era of massive ecommerce growth

The Indian ecommerce industry has overcome many challenges to become a $17.8 billion industry. But companies in this industry have to surmount a more difficult set of problems for online commerce to become the default method of shopping in the country.

When you go to a mall and look around you, what do you see? People, loads of them, buying everything from clothes and shoes to thronging the food courts. This is not how it was supposed to be. Those who have been following the fortunes of the ecommerce industry in India over the past decade will remember the almost hysterical statements about how modern retail would die out, malls would become empty shells, and everyone will buy everything online

On the contrary, organised retail is growing at between 20 percent and 25 percent annually in India. Online retail, according to the advisory firm RedSeer Consulting, grew at around 23 percent in 2017. That doesn’t seem too bad, does it? But look at the base. The organised retail industry is pegged at around $60 billion, while online retail is at just $17.8 billion. Despite this difference in base, the two segments are growing at a similar pace.

With many of the early challenges of the ecommerce industry — like awareness, logistics, and payments — getting solved to a certain extent, a more rapid growth was expected. That hasn’t happened because the next set of challenges might just be more difficult than the ones the industry has surmounted so far.

Beyond the top cities

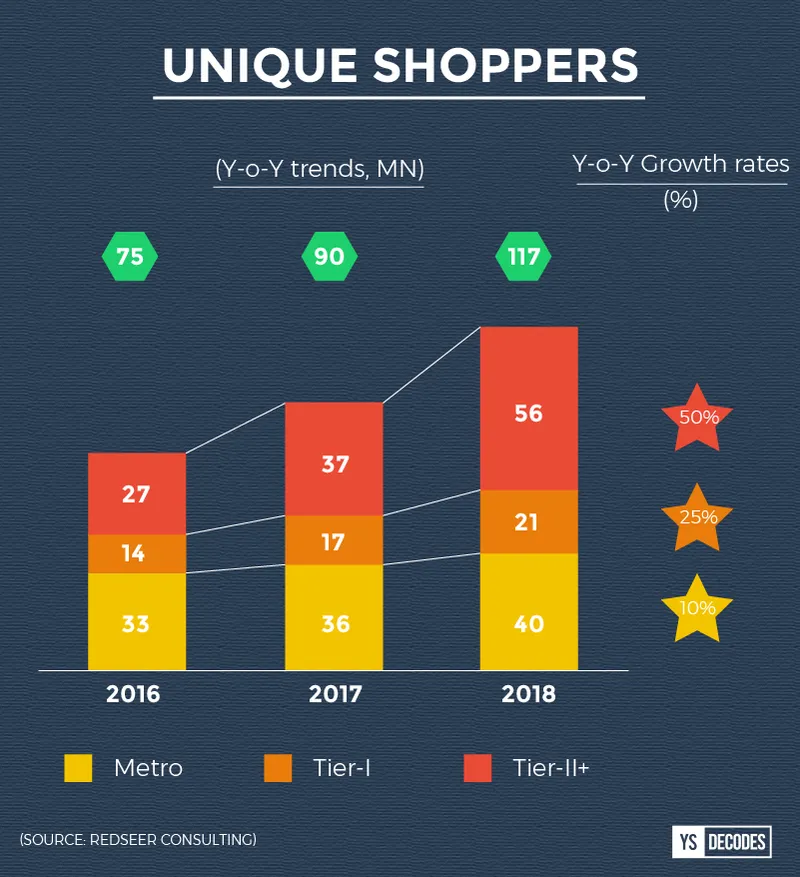

Online commerce has definitely grown beyond the top cities. In 2017, metro and Tier-I cities together had around 53 million online shoppers, while Tier-II and beyond towns were home to 37 million online shoppers, according to RedSeer. In 2018, the metro and Tier-I online shopper count is expected to reach 61 million, while the Tier-II towns and beyond count is expected to reach 56 million.

While the user base is growing, it needs to grow much faster. India had 480 million internet users by December 2017, but only 90 million of them shopped online in 2017.

A lot of funding has happened in ecommerce in the last three years, but the ecommerce companies have earned only a small chunk of customers. They have focussed on repetition of customers rather than widening the customer base, so there are less than 100 million active shoppers even now. Recovering this cost is hard – these customers won’t even purchase monthly,” says Satish Meena, Forecast Analyst at Forrester Research.

The difficulties in converting the small-town shoppers are manifold. The Indian market, as we have known for years, is not homogeneous. Ecommerce has a bigger challenge. They not only need to work on the awareness of brands and products among the shopper base, but also help them get used to shopping on a medium that they are not used to. Many new users have never accessed a website. For many, their connection with the internet is WhatsApp.

The first 20 to 30 million were the tech savvy ones — the Koramangala crowd who will try anything. The next set are not the tech savvy ones. That doesn’t mean they can’t become digital. We see auto and taxi drivers using apps to get bookings or vegetable vendors using Paytm to accept money. The shopping experience has to be seamless. All the new technologies using voice, chatbots, AI, vernacular messaging — all that will help,” says K Ganesh, serial entrepreneur.

Infrastructure improvement

It is true that logistics and payment infrastructure is much better now compared to even a couple of years ago. Amazon and Flipkart and numerous third-party logistics firms such as Delhivery, Ecom Express and others have ensured that much of the country is covered.

However, last-mile delivery is still a challenge in small towns. “Captive logistics coverage is lower for tier-2+ cities, where last-mile deliveries are done by 3PL partners; so, the logistics infrastructure is not as robust,” says Ujjwal Chaudhry, Engagement Manager at RedSeer Consulting.

There is a technological challenge that the companies are attempting to solve. “The last-mile address is unique in India. There are only four GPS systems in the world and we follow the American GPS in India. But unlike the US, India doesn’t have a block system, and in many cases, there are no door numbers, it is just a mohalla,” says K Vaitheeswaran, ecommerce pioneer and author of Failing to Succeed - The story of India's first e-commerce company.

While digital payments adoption has increased, Cash-on-Delivery (CoD) still forms a bulk of the ecommerce payments at around 65 percent. While cost of CoD is now similar to that of digital and card payments, the chances of returns and non-delivery goes up in this mode. Also, the value of purchase in the CoD mode is still low, with overall average annual online spend at around Rs 24,000.

Companies will need to create solutions that help customers overcome the trust factor, while making some of the bigger purchases more affordable.

EMIs, No-cost EMIs and Product Exchange features are currently available on select products but as this selection grows, it will be a large growth contributor towards getting new customers to shop online,” says Ujjwal.

Also Read: Paytm Mall claims GMV run rate of $3 billion; targets over $10 billion in FY2019

Sustainable business model

Companies have used practices like deep discounting to acquire more customers and ensure higher repeat order rates. This has led to low margins and high losses. Cash burn, the umbrella term for the money spent to acquire customers, is at around 15 percent of GMV a month right now.

India remains a value-sensitive market; hence, the margins in Indian ecommerce are lower than many of the large global markets. So, the biggest challenge in Indian ecommerce today is establishing a profitable business model in ecommerce,” says Kartik Hosanagar, who is a Professor at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

“People need to think how I can grow gross margins. That will come with exclusive deals or own labels. Own labels provide margins of over 20 percent to 30 percent. The ability to build own brands is an important requirement,” says Ganesh.

Companies such as Flipkart, Amazon, Myntra, BigBasket, Grofers and Pepperfry have launched in-house brands. Flipkart has announced its intention to launch private labels in 165 more categories this year. Amazon’s investment into Shoppers Stop was partly to get all of the latter’s in-house brands online exclusively on Amazon.in. Flipkart did double its gross margins in FY2017, before it launched many of its private labels.

But companies need to ensure a balance between private label and other brands. Vaitheeswaran says Indians prefer an established brand over an unknown one, even if the latter is slightly cheaper. Only Indian women’s ethnic apparel is an exception, as there aren’t many known brands in this category.

Companies need to be careful. Their private label sales need to grow but not faster than the branded business. If private label becomes a large contributor to sales, it might actually mean that the rest of the business isn’t growing. The concern then should be–is the consumer who wants branded goods going to other site or shop. Because a majority of the customer base wants the branded category,” says Vaitheeswaran.

This is why Myntra wants private label to contribute 35 percent to 40 percent to revenue and not more, and Flipkart is targeting 15 percent sales contribution from private labels this year.

But just increasing their private label capability is not going to help improve margins, if they continue to spend heavily on customer acquisition. With funding back in ecommerce, spends will go up drastically. Coupled with this, most companies, particularly single category players such as Urban Ladder, Lenskart and Firstcry, are expanding their offline presence. The cost structure there is very different, with rentals and other overheads. This too will eat into margins.

Regulatory hurdles

With the announcement of GST and 100 percent FDI in single brand retail, some of the regulatory challenges have been removed. “But there is still a great deal of work that companies like us have to do to adapt to these new policies,” says Rajiv Srivatsa, Co-founder of furniture brand Urban Ladder.

Within multi-brand ecommerce, the government has allowed 100 percent FDI only in pure play marketplaces. FDI is not allowed in multi- brand direct ecommerce. Most companies have resorted to complex company structures and are entering into multiple partnerships, like the Amazon Catamaran JV Cloudtail, to be compliant.

“Ecommerce companies work around rules now. Most have inventory, but need to use complex structures that lead to inefficiencies. If FDI opens up, resources can be diverted to better customer experience,” says the founder of an online fashion startup, who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

There is also the big challenge of finding their own identity.

My pet peeve — everyone seems to be doing the same thing for the same set of people. Only price is the differentiator. Each needs to identify a product or service differentiator,” says Vaitheeswaran.