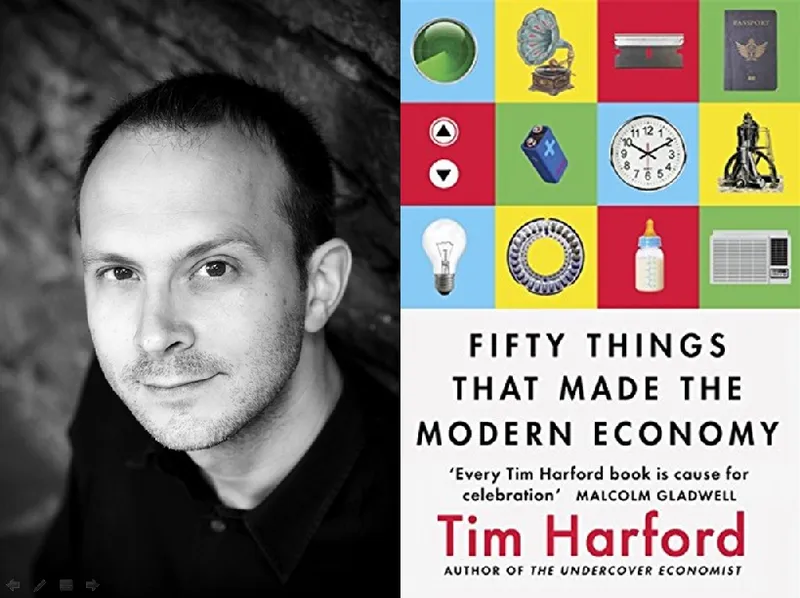

Master the art of spotting and fixing your mistakes – innovation tips from bestselling author Tim Harford

Following up on our book review of ‘Fifty Things that Made the Modern Economy,’ we interview the author on breakthrough technologies, the role of creativity, and how to bounce back from failure.

Tim Harford is the author of Fifty Things that Made the Modern Economy (see my book review). His other books include The Undercover Economist, Messy, Adapt, and The Logic of Life. He is a columnist for the Financial Times, presenter at BBC, and visiting fellow of Nuffield College at Oxford University.

Tim joins us in this interview on innovation trends, innovator agility, the role of culture, and the importance of government support for research.

YourStory: What is your current field of research in innovation and creativity?

Tim Harford: I continue to be interested in the impact of disruptions, distractions and obstacles to the creative process, as outlined in my TED talk.

YS: In the time since your book was published, what are some notable new findings you have had on the adoption or creation of inventions?

TH: The emergence of AlphaZero as an apparently serious force in artificial intelligence. It is always hard to evaluate quite how significant the new technology will be but from the outside it looks like a real breakthrough.

YS: How was your book '50 Things' received? What were some of the unusual responses and reactions you got?

TH: The book seems to have struck a chord. I think people have really enjoyed the mix of economics, history, technology and storytelling. But one of the things you learn when you describe 50 different diverse ideas and inventions, is that the specialists emerge with the fine print! I’ve learned a lot from that – although I have been encouraged that my initial story has usually stood up to expert scrutiny.

YS: It would have been great to see a detailed analysis of innovation trends and success factors in your last chapter – is that going to be another future book project?

TH: Well, my books Messy and Adapt discuss the creative process and the importance of trial and error in uncovering new ideas.

YS: Are there new models of innovation that you see coming from post-colonial societies? And from India?

TH: Yes, the idea of a ‘leapfrog’ technology is now quite well-established. I discussed one example in my book – the development and widespread adoption of M-Pesa mobile money in Kenya.

Some of India’s contributions are a great deal of mathematics, of course – and also possibly double-entry bookkeeping, although there is some controversy about that claim. More recently, Indian scientists have been behind some remarkable breakthroughs – for example, fiber optics – but sometimes outside India itself.

But I feel that I am poorly placed to identify Indian inventions! Like everyone I have my own cultural and geographical biases. I was very struck by this last year when I visited the museum of telecommunications in Berlin: the Germans had a very different idea of who invented the crucial technologies than the English and the Americans. It was humbling to see.

YS: How would you rate or assess micro-finance and venture capital as inventions/creations? They don't seem to be mentioned in your '50 Things' book.

TH: I wasn’t able to mention everything of course – there would certainly be room for another book with another 50 inventions.

Microfinance is interesting: it’s a useful innovation but the best evidence we have says it’s not transformative by itself. And while microcredit (small loans) is the easiest type of microfinance to develop and regulate, more useful products are probably microsavings, microinsurance and M-Pesa style payment services.

YS: It’s one thing to fail with a product, and a bigger dimension to fail with a company. How should inventors regroup in these two situations?

TH: This is something I discuss a lot in my book Adapt, and there are no easy answers. One important skill is – in the words of Nobel laureate Danny Kahneman – “make peace with your losses”. You need to be able to learn lessons without obsessing about what might have been.

A second important skill is early error-correction: get good data and honest, constructive feedback as quickly as possible, and you might be able to fix problems before they turn into complete failures.

YS: What are your thoughts on how the global always-connected digital society may accelerate the discovery and adoption of invention?

TH: So far, the evidence is that the rate of innovation is slowing down rather than speeding up. But there’s a chance that we’re on the verge of an upturn: let’s see!

YS: There is a lot of pressure these days on entrepreneurs and researchers to quickly find ‘commercialisation success.’ Will this dry up the focus and funding of basic research?

TH: That is something I worry about a lot. There’s a big role for government in supporting basic research directly, and perhaps tax incentives are needed too. Another possibility is major ‘innovation prizes’ – sometimes known as ‘Advanced Market Commitments’.

And there are clever ideas floating around to allow industries to impose a levy on themselves – a kind of club tax on all firms in the industry – and divert the revenue to funding basic research that might benefit the industry as a whole.

YS: What is your next book going to be about?

TH: I’m not sure yet. Possibly how not to be fooled in the world of fake news and alternative facts – or possibly another 50 inventions!

YS: What is your parting message to the startups and aspiring innovators in our audience?

TH: Try to master the art of spotting and fixing the mistakes you make.