The three crises of scale: how to bring back the founder’s mentality for success

This insightful book shows how many startups face challenges in the scale stage, but can overcome them by resurrecting the founder’s mentality. This renewal has been effective in companies such as Apple, Cisco, eBay, Dell, and 3M.

Many startups succeed in moving past launch and growth stage – but stall or even fail at scale stage. “Growth creates complexity, and complexity is the silent killer of growth,”according to Bain & Company partners Chris Zook and James Allen.

The research for their new book, The Founder’s Mentality: How to Overcome the Predictable Crises of Growth, is based on Bain’s FM 100 initiative for fast-growth companies. The material is well-presented with stories, tables, charts, checklist exercises, and references. The book’s online companion also offers tips on how agile teams can win “micro-battles” to bring about these transformations.

Here are my takeaways from the book, which will be useful for innovators and leaders in organisations of all sizes. See also my reviews of the related books The Road to Reinvention; Invent, Reinvent, Thrive; The Startup Way; and Blue Ocean Shift.

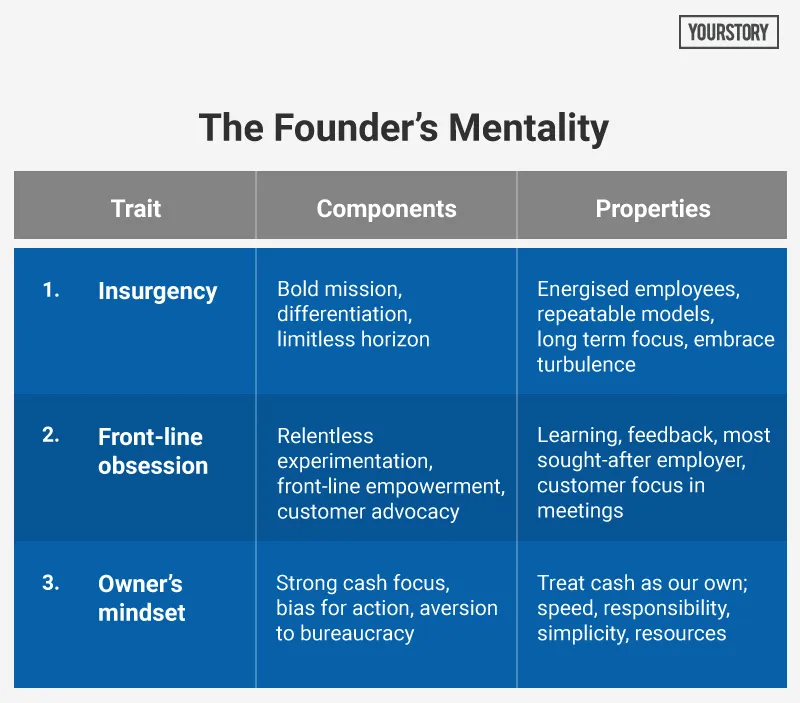

1. The Founder’s Mentality

Founders typically begin by rallying around unmet needs of underserved customers, or creating a new industry altogether. The mission is understood by all employees, who feel personal responsibility and emotional engagement. Success is powered by front-line employees who closely connect with customers and advocate their causes; they treat their job more as parents than babysitters.

This founder’s mentality (summarised in the table below) faces challenges in scale stage as the organisation becomes layered with complexity and struggles to retain or attract talent. Fast growth can also be followed by fast failure. The founder’s framework can sometimes be lost – but can be regained as well, and not just by the original founder but by committed new leaders appointed by investors or the board of directors.

Companies that have successfully retained the founder’s mentality are as varied as Google, IKEA, Oberoi Hotels, Haier, and AB InBev. Leslie Wexner’s L.Brands is also in this list; it includes companies like The Limited, Victoria’s Secret, Bath & Body Works, Abercrombie & Fitch.

Yonghui Superstores in China offers produce direct from the farm. In addition to large efficient stores, it has launched smaller innovative stores to challenge itself just as external disruptors would. Toyota’s factory production system empowers any employee to flag problems and submit suggestions.

Marico’s Harsh Mariwala transformed the edible oils market through practices like packaging oil in small plastic bottles rather than large tins, and creating a rural distribution network. Widespread participation led to the creation of its “People, Products and Profits” principles. This codifying, socialising and embedding of purpose is key to its success, according to the authors.

Oberoi’s hotel staff gets training in emotional intelligence and empathy; the slogan in the kitchen is “Improve Everything You Touch.” New employees are welcomed like royalty, and management meetings are open to employees as well. Even in his nineties, the founder had deep curiosity about every detail of guest experiences.

AB InBev does not invest in fancy offices; it focuses heavily on young people who have a hunger to succeed. It has acquired beverage firms around the world and constantly refines its practices and culture. “We create restaurant owners, not waiters. Owners take results personally,” according to one of the company’s principles. “We always think we can do more,” says CEO Carlos Brito.

2. The Challenges of Growth

After a startup or insurgent scales, it can become a scale insurgent, stable incumbent or struggling bureaucracy. Politics and bureaucracy can hinder the startup at scale stage, and prevent it from becoming a scale insurgent.

Stable incumbents are companies like Microsoft, HP, SAP and Gazprom. They still have leadership positions and barriers to competition, but are not as entrepreneurial or flexible as before, according to the authors. Struggling bureaucracies include General Motors, Kodak, Sony and Kmart, with a “poor state of inner health.”

Some founders cannot scale themselves, the newly hired managers bring different culture into the organisation, and the company loses touch with its customers. The broader perspective is lost, and planning windows shrink to the next quarter or year at best. Departments fight over turf and budgets. Healthy conflict is considered unprofessional, and criticism is taken as personal. Mediocrity wins over merit.

External challenges can come from new technologies, competitors, regulations, and crises – but many of the problems that bring companies down are also internal in nature. Internal challenges lie in the workforce, culture, processes, systems, cost management, organisational learning and leadership.

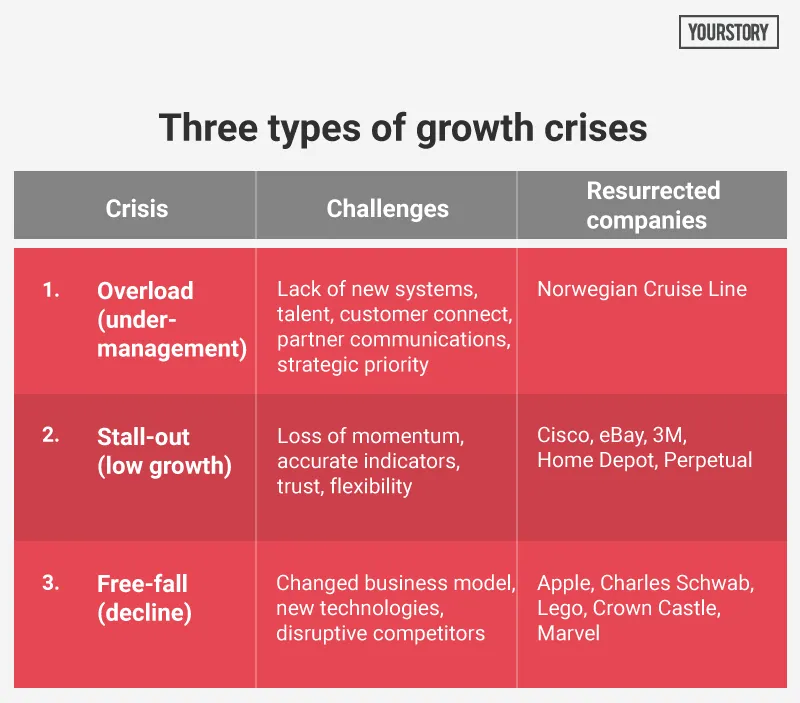

3. The Three Types of Growth Crises

The combination of internal and external challenges leads to three kinds of crises at scale stage: overload, stall-out and free-fall. The authors have come up with frameworks and case studies to show that bringing back the founder mentality by improving accountability, embracing new ideas, and adapting to new conditions can swing the fate of the company back to success.

Norwegian Cruise Line resurrected itself by improving internal communication, sharing tips on principles (Freestyle Fundamentals), starting a rewards initiative (Vacation Hero), adopting kaizen for continuous improvement, and codified best practices (Platinum Standards).

Cisco was facing competition from the likes of Huawei, Juniper Networks and Arista Networks. Its ACT program (Accelerated Cisco Transformation) moved the company away from non-core businesses, reduced product development times, created new project management software, hired engineers with expertise in fast moving products, and re-connected with engineers and customers.

Home Depot re-visited the founder’s principles outlined in their book Built from Scratch. Australian trust company Perpetual cut down its unsuccessful diversifications and re-focused on a crisp one-page strategy called One Perpetual. 3M overcame its engineers’ feelings of being “dejected and rejected” by re-kindling the spirit of internal entrepreneurship, self-belief and empowerment.

eBay revamped its e-commerce momentum by bringing in outside founders with experience in mobile commerce. Telenor partnered with Tameer Microfinance Bank to become a mobile payments player.

Charles Schwab resurrected his discount brokerage company by cutting down on “bad profits” from hidden fees, introduced norms for executives to listen to customer calls in the call centre, and replaced over 70 percent of the management.

Lego exited many of its adjacencies such as books, watches, dolls, TV and magazines. It cut down the unique number of elements in the toy sets, tapped ideas from its fans, added digital capabilities, and only then expanded into new avenues like co-branded products, eg. the Star Wars line.

“This approach – shrinking to grow – has been adopted successfully by a number of companies in free fall,” the authors observe. For example, Crown Castle cut down on some markets for its telecom towers, and focused only on areas with regional density.

Companies that went into free fall or obsolescence include Blockbuster, Lehman Brothers, and Sharp. Nokia was once king of the mobile phone market, but was too slow to invest in the future and act fast.

“Knowledge of the past is good, but defense of what is no longer working is bad,” the authors advise. Innovative and entrepreneurial employees need to be brought in, who have the knowledge and energy to succeed in emerging scenarios.

Thanks to Steve Jobs, Apple redefined itself at a time when market forces and industry boundaries were changing, and built new capabilities in digital content, retail stores, and developer communities.

Marvel Entertainment transformed itself from a bankrupt comic-book company into a highly profitable movie company; it was acquired by Disney for $4 billion. Total Renal Care reinvented itself as DaVita, with new branding, better internal coordination, and a culture devoid of formal titles.

IBM changed tack by investing heavily in software, consulting and IT services. Netflix renewed itself by building digital streaming capabilities. Fujifilm, unlike Kodak, moved successfully into digital photography.

In some cases, returning to private ownership can also help, as in the case of Philips semiconductor (NXP) and Dell. Michael Dell took the company private with Silver Capital, refocused on innovation, and went on to make the third-largest tech acquisition in history (EMC).

4. Leadership at scale

The concluding chapter offers advice and tips to leaders on how to ensure that the founders’ mentality can be sustained and scaled. “Make sure you have access to voices from the front-line. They are your best defenses against self-deception,” the authors advise. Seek feedback from them and respond to them.

Think beyond the short-term and devote time to recruiting and mentoring next-generation leaders. Create a long-term compass, eg. Unilever’s environmental sustainability plan. Be comfortable with holding opposing and contradictory ideas in your head.

Think “10X” – have bold ambitions. Stay away from “energy vampires,” and avoid ambiguity in objectives. Reward teams as well as individuals. Bring together veterans and new blood.

In sum, the book offers practical insights on how companies can retain the energy, focus, clarity, speed, adaptability, open-mindedness, behaviour, human vitality, and customer devotion of the original founders, and augment this with new talent and capabilities.

About the authors:

Chris Zook is a partner at Bain & Company and has been co-head of the firm’s global strategy practice for 20 years. His other books include Repeatability: Build Enduring Businesses for a World of Constant Change; Profit from the Core: a Return to Growth in Turbulent Times; Unstoppable: Finding Hidden Assets to Renew the Core and Fuel Profitable Growth; and Beyond the Core: Expand your Market without Abandoning your Roots. James Allen is a partner in Bain’s London office, and founder of the Bain Founder’s Mentality 100, a global network of high-growth companies.