Building a ‘Chakravyuha’ – cracking the complexities of modern slavery, including trafficking

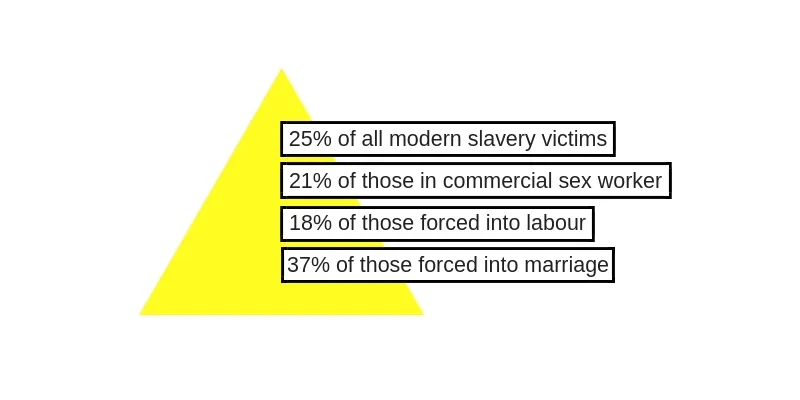

The true extent of trafficking continues to remain unknown because of the ‘latent’ way in which this complex criminal activity operates. Recently the discourse is around the usage of an umbrella term, ‘modern slavery’, which comprises of multiple concepts such as forced labour, debt bondage, forced marriage, slavery and similar practices, and human trafficking. Recent ILO global estimates of modern slavery state that 40.3 million human beings are victims of modern slavery, where 25 percent of modern slavery victims are children. The diagram below represents the percentage of children involved in different forms of modern slavery.

In India, the best estimates are about those involved in sex work, since studies on trafficking for labour or marriage are minuscule and insignificant. Researchers over the years have suggested widely varying estimates, ranging from 70,000 to 3,000,000 women and minor girls, of which 30 to 40 percent were assumed to be below 18 years of age.

The complexity of trafficking operates under the multiplicity of vulnerability such as poverty, illiteracy and unemployment, personal aspiration for a better life for themselves and their families, love affairs and the constant presence of persuasion and coercion in forced marriage, patriarchal norms and cultural practices, the traditional practice of commercial sex work, etc. India – known to be the source, transit, and destination in context of trafficking – gets the majority of its reporting from just a handful of states. Children get trapped in trafficking for multiple purposes including commercial sexual exploitation, labour (particularly domestic work, or industrial/agricultural farm labour), marriage, adoption, etc.

However, the Lok Sabha has just passed the much-awaited Trafficking of Persons (Prevention, Protection and Rehabilitation) Bill, 2018, calling in the timely and effective prosecution of offenders, greater accountability of the rehabilitation agencies, and strengthening convergence and functioning of special units to address the complexities of trafficking. Although there are still glaring gaps such as those related to forced begging and migrant trafficking which need urgent attention, I am hopeful those will be ironed out on priority to not dilute the attention and service our children deserve.

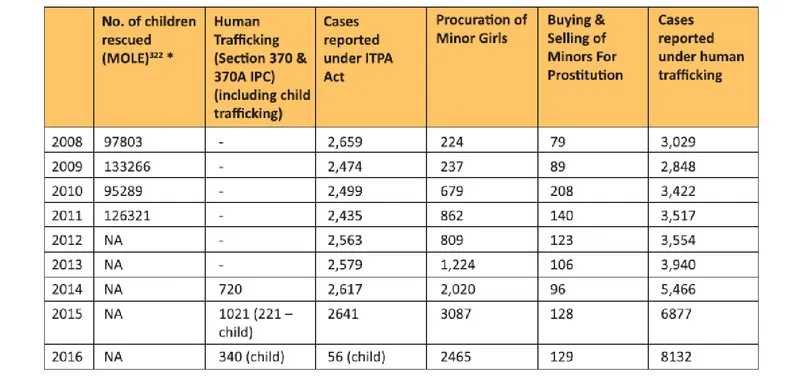

The biggest data gap in the context of child trafficking in India continues to be the astronomical difference between the estimates of trafficking for various purposes and complaints/cases registered in the legal domain. Cases that come before the legal enforcement system are way less in number due to multiple reasons such as social/economic demand, tolerance of sex work, poor enforcement, political patronage, and low prioritisation of trafficking as a socio-legal issue. In 2016, the number of cases reported under human trafficking was 8,132. Until 2014, sections under IPC predominated the number of cases filed, which largely comprised of those for the purpose of sexual exploitation, accompanied by cases filed under ITPA, 1986.

Since 2014, cases reported for human trafficking have been added to the statistics, though very few cases of forced labour/trafficking for labour purposes are yet to be reported. The NCRB annual crime statistics gives statistics related to the Immoral traffic prevention act, 1956, and human trafficking under Section 370 of the IPC (only available in recent years). It also inputs cases under human trafficking from a collation of cases under Sections 370 and 370A and procuration of minor girls (Section 366-A IPC) and Buying of Minor Girls for Prostitution and cases under the Immoral Traffic (P) Act, 1956.

Among others, the data for those under 14 years of age is disaggregated, and for those between 14 to 18 years, data is unavailable. It is also noteworthy that the majority of the reported cases are from a handful of states, with the maximum from Assam, West Bengal, and Bihar. I sincerely hope the revised legislation, along with looking at various nuances, also pays equal attention to how we could best combine trained staff and technology to address the ambiguity around data. After all, what gets correctly noted has a higher chance of getting acted upon.

Historically, child protection in India has just received a piece-meal approach with multiple ministries and departments working on the issue and having minimal convergence across separate thematic areas. Children deserve much more than what restricted child protection systems have on offer. The act of trafficking, not being straightforward, involves a child being treated as a commodity, passing through multiple hands, and receiving varying degrees of abuse at each successive step. The way I see it, the most probable way to address the complexity of the issue also lies in strategically addressing the complexity, such as executing a multi-tiered formation in a Chakravyuha.

We need the political will to evolve an excellent planning and execution plan to overcome the present complexity in this trade. We need a large number of soldiers and undoubtedly adequate resources to build this Chakravyuha, followed by heavy investment in training of our soldiers who will fight in this chaos until the battle is won.

Puja Marwaha is CEO of Child Rights and You (CRY).

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of YourStory.)