The next recession could be here sooner than you thought and this time, look East, not West

On November 23, when the S&P 500 index hit a 10 percent fall from its yearly high of 2930 points in mid-September, there were familiar whispers of the markets heralding a moment of reckoning for the US economy. There has been a steady expansion in the US economy for close to nine years since the Great Recession ended in June 2009 and arguments in favour of a looming recession next year are basically of two types.

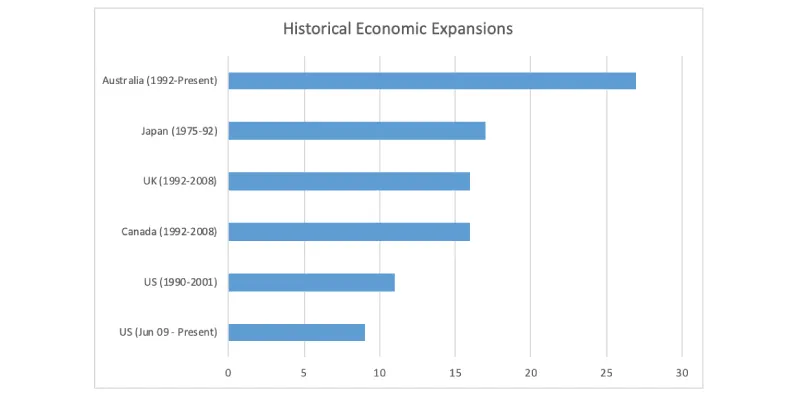

One is based on an empirical analysis of historical data – the US has never had such a long period of economic expansion between two recessions. Statistically speaking, post-war US has seen a recession around five years after the end of one, with an over 90 percent likelihood of that happening within 10 years of economic recovery and expansion. By this measure, an economic slowdown is overdue next year.

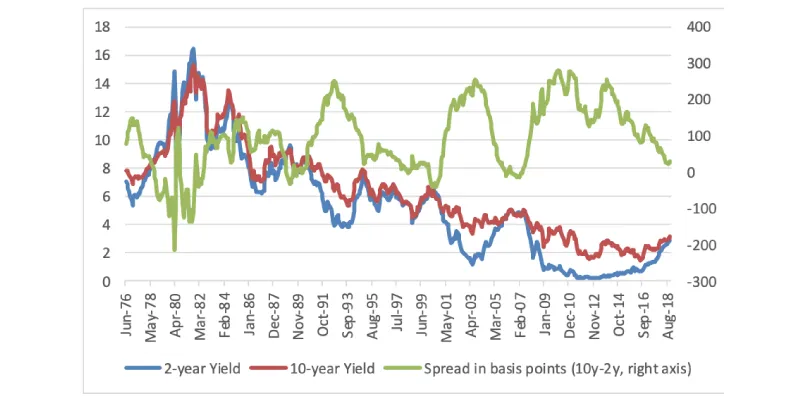

Second, as economists who prefer more rigorous analysis point out - the yield curves are flattening. In the bond markets, normally the longer-tenure bonds (10- and 30-year) have higher yields than shorter-tenure ones (1- and 2-year) as investors demand a greater interest rate for locking their money in for a longer period of time. This would also offset the uncertainty around short-term rates in the future.

However, should investors believe that inflation will sharply decline in the future, or that the economic performance will worsen causing the US Federal Reserve to cut interest rates sharply, they are less likely to demand a premium on holding long-term bonds. Therefore, the difference in yields between long-term bonds and short-term bonds (or spread) should fall (flatten).

Indeed, that is something that has been happening - the difference between 10-year and 2-year yields fell from 1.29 percent at the end of 2016 to 0.26 percent currently - a drop of 103 basis points over two years. Given that the yield curve inversion (when short-term bonds have higher yields than long-term bonds) has been an incredibly good leading indicator of US recessions over the last 60 years - forecasting every single one of them - the flattening of yield curves suggests the next recession is just around the corner - maybe next year.

Ominous as these signs are, we believe the likelihood of a recession in the US next year remains negligible – notwithstanding President Donald Trump’s blunt force approach to global trade (more on this later) and the inability of successive US governments to address the structural issues with the quality and targeting of public spending, while containing the fiscal deficit and debt.

First, the analysts pointing out the unusual length of the US expansion since the Global Financial Crisis forget how uniquely lacklustre US recovery was in the initial part of this cycle. Between 2009 and 2014, US GDP growth averaged 2.2 percent, well below the 2.8-3 percent growth rate seen in the previous periods of expansion. It only picked up to the 2.8-3 percent level this year, which means the ‘overheating economy’, which we are being warned about, may yet be a few years down the road, perhaps sometime in 2020.

Moreover, no two past crises were similar and were triggered by unique catalysts. The 2007-09 crisis was a result of a crash in house prices, the 2000 crisis was led by the dotcom bubble burst, and the ones in the 1970s and 1990s were in response to geopolitics and oil price shocks from the Middle East. None of these catalysts seems to be on the horizon in 2019; oil supply from the Middle East does not seem to be a concern given the discovery of shale oil has made the US more self-reliant. Finally, long periods of economic expansion without a recession are not unusual if we tend to look beyond the US.

Australia is in the 27th year of economic expansion, having avoided a recession since January 1992. Japan (1975-92) and UK (1992-2008) have had long periods where the economy did not naturally overheat and encounter a recession at regular periods.

The argument that points out at the flattening yield curve as the harbinger of the next US recession ignores how signals inherent to the yield curve have transformed in a world where major central banks have undertaken quantitative easing. First, the pace at which the US Fed unwound its balance sheet since Q4-2017 has been gradual, whereas rising fiscal deficit over the past three quarters has meant a greater issuance of shorter maturity bonds. This implied an oversupply of short-tenure bonds relative to long-tenure ones which the Fed is only gradually selling off as it undoes the QE stimulus.

Ergo, yields at the longer end of the curve remain supported, whereas oversupply on the shorter end keeps rates higher. Second, despite the unemployment rate falling to its lowest level in the post-war US, we have not seen a concomitant pick-up in either inflation or wages. It has been interpreted by a number of economists, including some at the US Fed, that inflation is likely to remain permanently lower compared with the levels before 2008. If the inflation risk falls in the future, it should encourage holders of longer-tenure bonds to seek a lower lock-in cost (yield) for their cash in fixed income securities, further pushing down long-term rates.

Between the noise of a market crash, a historical precedent, and flattening of the yield curve, it is easy to forget these data points are indicators of a future recession based on some assumptions. And, as discussed above, those underlying assumptions have been severely challenged in the current cycle of economic expansion.

Housing markets are improving but are far from overheating; mortgage credit is picking up, though under a more strict regulatory regime; consumer sentiment is near its peak, and retail sales and corporate profit margins are not yet flashing danger signs. As of now, it seems as if the fiscal stimulus unleashed by the current administration ($700 billion through repatriation of earnings, $100 billion in extra spending and $200 billion in tax cuts) is likely to provide enough boost to corporate earnings and consumption even in the coming year.

However, a slowdown two years down the line cannot be ruled out as the fiscal stimulus runs its course - persistent debt and deficit constraints come to bite and the current administration’s ill-informed trade policy begins to manifest itself in the disruption of global supply chains and a trace back in investment sentiment.

Though we are closer to the end of a cycle of economic expansion, it is unlikely that next year could see the US economic growth grind to a halt.

Even though it would be extremely bold to hazard a guess, I would say the next US recession would be shallower than in 2008; and would likely come from a corporate debt market crash.

As quantitative easing pushed down interest rates across the board in the US over the past ten years, the issuance of bonds by companies with questionable balance sheet metrics and risky business models has been on the rise. Indeed, the issuance of junk bonds or bonds with ratings lower than BBB (S&P) is higher today than it ever was even at the peak of the mortgage lending euphoria in 2006-07.

That said, inter-sector linkages of corporate debt are weaker than that of mortgage debt, as it was in the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis. Securitisation of corporate debt is tightly regulated and it is unlikely that a debt market crash could leave both, businesses and households’ balance sheets severely impaired. Furthermore, should the next crisis come from the corporate debt side, the recovery is likely to be quicker than the past recession. The exceedingly slow recovery in the current US economic cycle owed a lot to its nature – housing markets. Underwater homes meant people were still tied to a steep housing debt, which they were unable to pay and hence were unable to move jobs and regions - an essential catalyst for re-allocation of resources post a recession.

That said, markets may just be looking in the wrong direction when it comes to checking the symptoms of the next recession - rather than looking West, they could perhaps pay more attention to the East - China.

Analysis-wise, there is not as much to dissect in China’s data to come up with the probability of a recession. Chinese statistical authorities have been famous for keeping bad news about the economy close to their chest, revealing it many years later only when the pain has passed.

There is, therefore, a high likelihood that even when a sharp deterioration in the Chinese economy takes place sometime next year, we may only see it being gradually reflected in economic data.

But before trying to divine the likelihood of a slowdown in China next year, let us just recount - for the sake of Indian readers who tend to underestimate its economic heft - some numbers. Schwenza (2013) calculated that as of 2011, China produced 91 percent of world’s computing equipment, 80 percent of its lighting equipment, 74 percent solar cells, 71 percent mobile phones, 63 percent shoes, 60 percent cement, 48 percent coal and 45 percent ships and shipbuilding equipment. A recession, or even a 2-3 percent year-on-year slowdown in China, hurts everyone - wherever they are.

If this is so, what may bring about a slowdown in economic growth? Something way beyond what the government has been broadcasting as a slow normalisation in the 6-6.5 percent growth range by 2020. Though it may occupy much news space these days, a trade war, with tariffs and sanctions on China, is unlikely to induce an economic slowdown on its own.

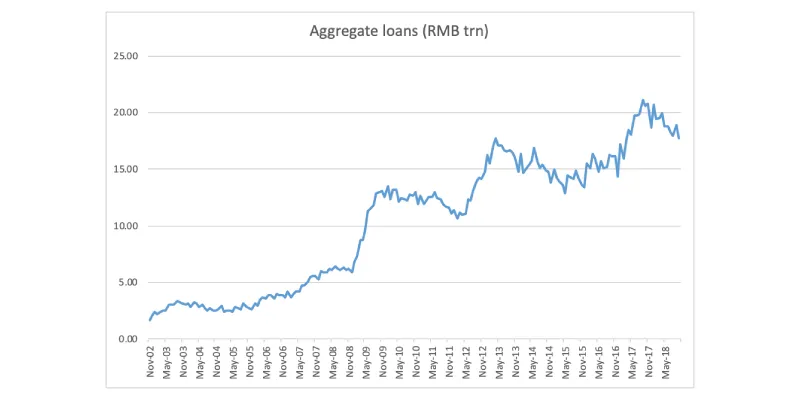

Though it is massive relative to the world, trade contribution to China’s GDP growth has been less than 0.5 percent consistently since 2013 – and exports to the US are only 19 percent of the total. This also indicates the enormity of its domestic market. A likely trigger to the so-called “hard landing” in the case of China could come from its inability to stimulate the credit growth in the economy, despite monetary easing.

That China’s total credit to GDP ratio (from 140 percent of GDP in 2008 to 260 percent now) has been a perennial risk to the stability of the global economy has been known for quite a few years now. Indeed, in October 2017, former PBoC Governor Zhou Xiaochuan pointed out that China was nearing a “Minsky Moment”, where he warned that excessive growth in corporate and household lending could lead to a sudden crash in asset prices, leading to a completely unanticipated economic slowdown.

Since then, the Chinese government has been walking the tightrope between balancing an orderly deleveraging of the economy without causing rapid deterioration in growth. However, even a government so centralised in authority, and powerful in its policy-making ability as China has had to make compromises towards its agenda of de-risking the economy through an orderly default and resolution of sick enterprises in the mining and heavy industrials sector thanks to the powerful factions within the Communist Party who have interests in such businesses.

There are credible reasons to believe that China’s moment of reckoning could come this year, as it may not satisfactorily be able to address its debt problem. Data through the second half of this year shows the credit appetite of Chinese firms has been waning – possibly because a number of businesses in the market are so overladen with debt servicing that they do not want any more loans.

Despite four cuts to reserve requirement ratios this year and local governments’ efforts to boost construction spending, the credit growth rose in October at the slowest pace since the financial crisis (see chart). Also, the government announced tax reductions on import tariff on machinery, electrical equipment and textile products – industrial profits, which we estimate to be an important indicator for future investment spending, have softened for five straight months and now sit at a seven-month low.

If credit growth continues to languish and industrial profits remain subdued for another two to three months, we believe it could point towards a steady deterioration in demand conditions later next year, perhaps resulting in a higher likelihood of a hard landing.

That said, given the Chinese government’s cautiousness while broadcasting bad news, we may never know the extent and timing of such a slowdown if we continue to look at the headline GDP numbers.

Nevertheless, for firms with business interests in China, such pains may come in the guise of lower export orders, less willingness to finalise FDI and investment deals, and a general crash in the price of industrial commodities. The troubles, if they flare up in China, will be too big to hide, and hide from.

Also read: India 2019 general elections: The critical overs of the power play begin