World Leprosy Day: what the Indian government is doing to achieve its goal of a leprosy-free India

On World Leprosy Day, observed on January 30 in India, we take stock of how far the country has come in its battle against the disease.

India has taken mammoth steps in the past decade. We've emerged as an economic powerhouse and become a strong force on the global front. We even halved the poverty rate. But we are still struggling to do away with many of its dire by-products. Among them, leprosy remains a major concern.

Though it is curable, many people continue to suffer without ever receiving treatment. Data reveals that annually about 60 percent of the new cases worldwide are from India. Recently, the government has taken up creative initiatives to tackle this situation.

Situation right now

In August last year, a village in the Baloda Bazar district of Chhattisgarh caught the attention of the National Leprosy Elimination Programme (NLEP). They detected an outbreak in the village. It is one of the 24 districts across the nation where the government has declared a high endemic of leprosy. As the state continues to battle poverty, Chhattisgarh, which has two percent of the nation’s population, clocks an Annual New Case Detection Rate (ANCDR) of nine percent.

The Annual New Cases of Grade 2 Disability (G2D), indicating irreversible damage, is at 3.34 cases per million population. And ours is a nation of 1.32 billion people. This would mean that more than 4,000 people with leprosy every year are finally being documented after years of silent suffering.

A statement from the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare noted that by implementing the Leprosy Case Detection Campaign (LCDC) they were able to detect 65,000 new cases per year, and through prompt treatment could preempt Grade 2 Disability.

The NLEP revealed that the delay in treatment in remote areas was due to a lack of awareness, and the stigma surrounding the disease. It was also noted that accredited social health activists (ASHA) and primary health centres (PHC) have not been proactive in the community. Reaching out to the marginalised sections is vital to managing the spread of the disease.

Tackling stigma through awareness

To understand how the government is handling the situation, SocialStory spoke to Dr Anil Kumar, Deputy Director General (Leprosy), NLEP, who threw light on how the NLEP and the Sparsh Leprosy Elimination Campaign (SLEC) --a year-long campaign by the Centre, which culminates in October 2019, aiming to reduce the annual new cases of G2D to less than one case per million population--function.

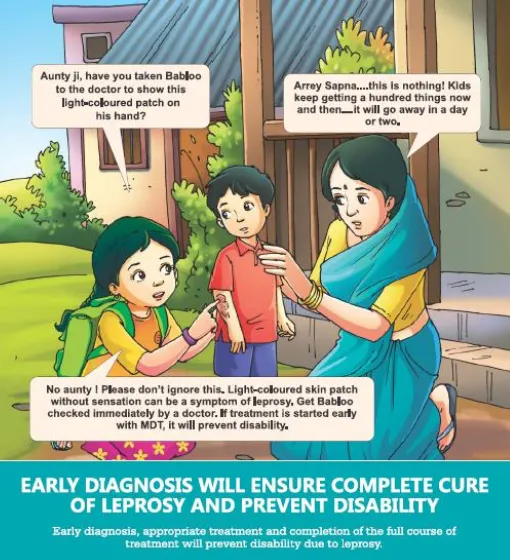

The Department’s mascot, ‘Sapna’, is a fictional twelve-year-old girl who takes up the responsibility of spreading leprosy awareness in her community. The concept emulates UNICEF’s successful Meena Campaign for Girl Empowerment.

The idea was to spin a positive outcome from awareness and not concentrate on the negative aspects of the disease.

“We no longer show disabled people on our posters. We try to add some positivity by using our mascot Sapna who is a regular schoolgirl,” Anil explains, adding that the image of leprosy as an adverse disability is detrimental. “People should stop associating leprosy to the image of extreme disability. It is much like any other skin disease that can be cured completely. If detected early any bit of disability can be avoided,” he says.

On the stigma associated with the disease, Anil says, “Though the stigma attached to the disease changes from place to place it has definitely reduced in our nation on the whole.”

The vaccination approach

The NLEP has started issuing the Mycobacterium Indicus Pranii vaccine, which was developed in India, on a trial basis.

“Recently, we have started an experimental project for the use of MIP vaccine. We are administering it in a district in Gujarat, and according to the results we’ll expand the project,” Anil adds.

Also read: Mother Teresa of Pakistan and her fight against leprosy for over half a decade

The bacteria that causes the disease has an unpredictable nature. “It is also important to note that almost nine out of 10 people are immune to the bacteria. But it is not possible to determine exactly who are at risk of contracting it and those who are not,” he says.

He, however, adds that a vaccine alone won’t do the needful. “We need to tackle leprosy from many angles,” he says. “Vaccination along with multidrug therapy (MDT) and better awareness will rid the nation of G2D.”

What’s in store for 2019

Anil is hopeful for 2019. He says that the NLEP has formulated a comprehensive plan for this year.

The G2D cases detected per million has dropped significantly in the last three years to 3.34 annual new cases per million people. The Ministry hopes to reduce this to less than one case per million people by October this year. They've set this target in commemoration of the 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi, on October 2, 2019.

To make this happen, the NLEP will organise two case detection campaigns in the next eight months. Patients with symptoms will immediately be put on MDT, and people who have had a prolonged interaction with those affected will undergo Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP), a precautionary medical treatment to strengthen the immune system against the disease-causing bacteria.

“With our focused and steady efforts we’ve been able to halve the G2D since 2014. For this feat, NLEP has got global recognition,” Anil notes.

Also read: This Japanese photographer is on a mission to remove leprosy taboo in India

The NLEP provides medical rehabilitation to those who’ve already incurred G2D. They can undergo free reconstruction surgeries and also avail a monetary compensation for their post-op recovery. Additionally, they get support from many governmental and non-governmental organisations, Anil adds.

He makes a passionate appeal to reduce the stigma surrounding leprosy. “People need to understand that you can sit and eat with affected individuals without putting yourself in any harm. Disabled people already undergo a lot of psychological pain. Discrimination will completely distance them from society. Once an infected person starts his course of medication there is almost no chance of him infecting others,” he says.