Ensuring business success and resilience – the why and how of leadership coaching

This compelling book explains the nuts and bolts of coaching as a necessary trait for leaders. This is particularly relevant during crises like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Launched in 2012, YourStory's Book Review section features over 290 titles on creativity, innovation, entrepreneurship, and digital transformation. See also our related columns The Turning Point, Techie Tuesdays, and Storybites.

Companies succeed and thrive when leaders groom the next wave of leaders through coaching, as explained in the compelling book Coaching: The Secret Code to Uncommon Leadership by Ruchira Chaudhary.

However, this calls for skills and discipline in balancing managing and guiding. The book’s lessons are particularly useful for organisations in turbulent times like the pandemic era. Conventional command and control practices are yielding to more agile, collaborative, and emergent models.

The author features a mix of insights from business leaders and academics, and the use of examples from India and overseas will make it accessible to a global audience. The book is thoroughly referenced, with 30 pages of resources.

Ruchira Chaudhary is a business coach and consultant with a background in mergers and acquisitions, organisation design, culture, and leadership. Her two decades of experience span Medtronic, AIG, Commercialbank of Qatar, Qatar Telecom (Oredoo), and TCS. She is also affiliate faculty at SMU, NUS, and University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business.

Leadership today is more about being collaborative than prescriptive, asking the right questions than having all the answers, Biocon Chairperson Kiran Mazumdar Shaw writes in the foreword. Employees should be problem-solvers and not task doers and should be empowered to find their own purpose and path.

Coaching helps build scalable innovative organisations. Leaders should guide, enable, inspire, and transform, she adds.

“Coaching is essentially about helping others grow; and when you do that, you grow yourself as a person and a leader,” Ruchira begins. Coaching is also a life skill and applies to all employees. Coaching is a key to generative leadership.

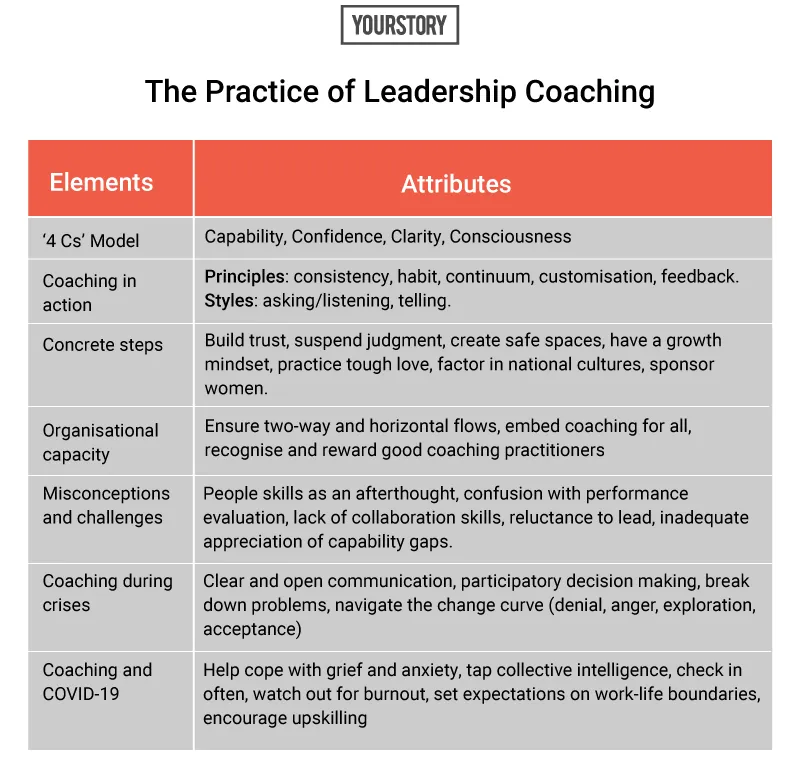

Here are my key cluster of takeaways from the 400-page book, summarised as well in the table below. See also my reviews of the related books Multipliers, The Culture Code, Trillion Dollar Coach, What You Do is Who You Are, Rebel Talent, The Messy Middle, Entrepreneurial StrengthsFinder, The Moonshot Effect, Manager’s Guide to Mentoring, and Global Tilt.

Check out our earlier write-ups on the TiE Bangalore Mentorship Panel, Crisis Communication, and pick of 60 Quotes on Coping with Crisis and 75 quotes from India’s COVID-19 struggle.

Foundations

Coaching maximises performance and potential through non-directive and self-enabling conversations, the author explains. Leaders need to cultivate a more collaborative and collective approach to running organisations.

Cricket has shown that not all great players become effective captains, and many captains have not been star performers either, Ruchira shows. “Core talent should not be misconstrued as the ability to lead,” she cautions.

Some star performers are best left to perfect their craft, rather than being saddled with the pressures of leadership. It is, therefore, important to identify who is willing and interested in being coached, and shows leadership potential through collaboration and feedback.

“Coach only the coachable – those that demonstrate a willingness to change, a desire to work hard towards new goals, and most importantly, are open to learning,” Ruchira advises.

Human capital depends on workforce knowledge and the ability to create value and excellence. Raw talent coupled with grit and guidance can work wonders – the combination of nature and nurture is key. Unfortunately, not all business managers are good people managers, and not all experts are good teachers.

Though external coaches can be deployed, coaching is not a separate activity for leaders and should be embedded in their mindset and skillset. Coaching needs to be supported at all levels of the organisation.

“You cannot be a good leader or manager without being a good coach, Ruchira affirms.

“Remember to differentiate between a Coach, a Couch, a Cheerleader, and a Crutch,” she jokes. A coach guides current practice, while a mentor guides career or life journeys.

The ‘4 C’ Model

Ruchira’s model of coaching is based on four cornerstones. Capability helps people chart their own path, spark creativity, and envision what is possible beyond the horizon.

Consciousness increases self-awareness, and Confidence improves self-belief. Clarity gives direction through core compelling questions and taking away the noise.

Coaching is about pointing out the facts and going beyond identifying weaknesses to learning and strength-building. It helps uncover biases and blind spots.

“Greater introspection, self-reflection, and feedback from co-workers aids the process of self-discovery,” Ruchira explains.

Coaching is not about therapy, and it is not a one-way dump of knowledge either. “Coaching is nudging – not nagging,” she adds. Coaching is also not just about annual performance assessment or offsite events.

Being a good coach calls for time, interest, energy, mindfulness, emotional intelligence, courageous conversations, and preparation. Unfortunately, some managers fear that if they coach others, they may be outshone.

The book builds on other frameworks on leadership and organisational development, including ABCD (Always Be Connecting the Dots), GROW (Goal, Reality, Options, Will), RARA (Recognise, Ask, Reframe, Action), and ARC (Architecture, Routines, Culture).

Coaching in action

These four cornerstones of coaching are supported by a set of principles and manifest in a range of styles. Good coaches are active listeners. They should probe to find collaborative behaviours and some details of personal life as well.

They should build trust by delegation and creating safety to ideate, experiment, make mistakes, and learn from failure. Coaching as a habit should be practised formally and informally throughout the year, Ruchira advises. This includes coaching conversations in corridors, hallways, curbsides, and even taxi rides.

The Japanese practice of Gemba involves “going to the place where value is created,” and discussing business practices on the shop floor and not just the boardroom.

Leader coaches should be consistent in their behaviour and surround themselves with exceptional people. They strike a balance between managing and guiding between market pressures and employee needs.

Though it can be lonely at the top, leaders themselves should be open to being coached and rope in outside coaches as necessary. “Coaching is about using the ‘F’ word often,” Ruchira emphasises, referring to the importance of constructive feedback.

Coaching and customisation

Coaching should be customised as well with a blend of technical skills, general tactics, business principles, and life lessons. Employees at early stages in their career may need more encouragement and positive feedback, the author observes, while later-stage employees want more critical feedback.

Stars, steady performers, and strugglers need different kinds of approaches as well. Recognition encouragement and new opportunities need to be offered in varying degrees, Ruchira explains.

Telling or instructive coaching may be good for expert knowledge transfer in standardised tasks, whereas asking and active listening involves more compelling questions with less judgment. At different times, coaches can be teachers, role models, or mirrors.

Allowing the solution to emerge helps employees feel they own the solution as well. Coaches should be “honest without being harsh,” and end the session with practical actions and follow-on steps.

Leader coaches are givers, not takers. They respond freely to high-impact opportunities and help those in whom they see the potential.

Leaders also need to find the balance between showing love and being tough (“tough love”). They should be assertive but not aggressive or abusive, Ruchira cautions. Coach roles should know when to give a “pat on the back or a kick in the butt,” as seen in the world of parenting – but this should come from a position of love.

Being only tough leads to demotivation, but being only nice leads to tolerance of non-performance. Tough love can be strong criticism on a faulty presentation – followed by a round of drinks at the end of the day. Being a “straight-shooter” helps, but so does giving appreciation.

Coaching matters even more for women, Ruchira argues, citing research which shows that women tend to have a self-confidence gap, are risk averse, and undervalue their worth. Women should be connected to more networks, and leaders should champion, sponsor and invest in initiatives for women.

One chapter deals with coaching in different international and cross-cultural contexts. For example, coaching in collectivist cultures is more of teaching, telling, or advising, since managers are expected to look after employees in exchange for their loyalty.

Japan’s consensus-based culture is also hierarchical with behind-the-scenes persuasion and lobbying. This is in contrast to the more agile model of Silicon Valley or entrepreneurial spirit of Indian managers, Ruchira observes.

The Netherlands also has a consensus-based culture but is more egalitarian with buy-in only after rationalisation. German companies prefer an authoritarian approach, whereas Swedish employees expect to be consulted.

Global leader coaches need to be culturally aware and flexible, and adapt to these cultural dynamics without falling prey to stereotypes as well, the author cautions.

Organisation-wide coaching mindset

“Culture cascades from the leader,” Ruchira explains. For the leader-coach model to succeed, principles and practices of coaching should be embedded in systems, processes, and beliefs as well. This is particularly important for matrixed organisations.

In Microsoft, coaching is now a clear expectation from every manager. People are evaluated and rewarded for teamwork, communication, and connection with others. Parallel tracks are offered for those who do not want to lead but stick to tech roles, for example, work on larger projects.

Coaching should be integrated with performance management, incentive structure, recruitment, and promotion, and the work of great coaches should be celebrated regularly, Ruchira advises.

One chapter addresses how external coaches can be brought in during times of organisational change, career transitions, and helping executives get unstuck. Though they do not have the depth of the organisation’s context, they bring in objective perspectives and valuable insights from other industries.

Coaching during a crisis

Two sections of the book focus on leadership and coaching during a crisis, with a special focus on the COVID-19 pandemic.

Open communication, positivity, and outlining manageable steps are key. It is important to listen to people even when the answers or solutions are not known. Fears and objections should be listened to, and denial should be countered.

Broader participation in brainstorming should be encouraged. People should be allowed to take initiative and learn from mistakes, Ruchira advises.

The pandemic has led to risk to human life, and abrupt changes in business models. Leaders have to guide and coach in uncertain times and even in the face of conflicting advice from experts.

“Perhaps, the most troubling aspect of this pandemic is the open-endedness of it,” Ruchira laments.

There are feelings of grief and disconnectedness, and leaders have to assure their employees that it is okay to say they are not okay. The context is complex, not just complicated.

Leaders have to operate at a “far greater scale and with much more intensity.” Frequent check-ins are needed to ask employees how they are doing. New work-life boundaries need to be calibrated.

Leaders should exude “bounded optimism,” and focus on controllability, Ruchira advises. People should be encouraged to introspect, reframe, reinvent, and upskill.

“Coaching has never been more important than it is now,” she observes. “Trust and resilience will be your rudder as you coach your way to uncommon leadership,” Ruchira signs off.

Examples

The book is packed with examples of leader coaches in action. For example, Satya Nadella modelled the kinds of behaviours he wanted to see in Microsoft, such as soliciting ideas from everyone, active listening, and non-directive questions.

Leaders who had good coaches include Jeff Bezos (Bill Campbell), Alan Lafley (Peter Drucker), and Jack Welch (Ram Charan). Vivek Ranadive was not just CEO of TIBCO but also a basketball coach.

Thomas Crosby, CEO of fast-food chain Pal’s Sudden Service, regards his company as an education company with leaders as teachers. Each day, managers spend 10 percent of their time helping a promising employee. Thomas has assembled a list of 21 master books, discussed each Monday with the managers.

George Lucas gave full support to newcomer Ben Burtt to develop the voice of robot R2D2 in Star Wars. Comic book legend Stan Lee gave his artists real responsibility and did not breathe down their necks. Herb Kelleher of Southwest Airlines strengthened a work culture of empowerment and fun through storytelling as coaching material.

ICICI’s founder KV Kamath is credited with building a long line of leaders. MakeMyTrip’s Deep Kalra invites young hires to client meetings. New managers are HUL are assigned a senior manager as coach, who is assessed for performance. Epigamia founder Rohan Mirchandani has an operating mantra of fast decision-making and a safety net for learning from failure.

Examples of brash leaders include Uber’s Travis Kalanick and Enron’s management, who focused more on growth at all costs and individual stars rather than long-term success and collaborative culture. Narcissists make the worst managers and do not accept responsibility for mistakes.

Shatbdi Basu became India’s first woman bartender and started the STIR school to groom other aspiring bartenders. Bhutan’s JSW School of Law is inclusive and empowers students to shine brighter without fear of consequences.

The movie series Kung Fu Panda also offers valuable coaching principles and life lessons, Ruchira adds. Examples include: “There is no secret ingredient. The secret ingredient is you.”

Examples of leadership by women heads of state during the COVID-19 pandemic are also highlighted: New Zealand (early self-isolation), Norway (prime minister’s TV talk to children), Finland (early use of social media influencers), Iceland (free testing), Germany (alert leadership, reliance on science), and Taiwan (leveraging learnings from the SARS experience).

In sum, this comprehensive, systematic and practical book is a must-read for leaders, managers and founders, particularly in these tough times. The breadth of professional insights and personal anecdotes makes it accessible for a broad audience as well.

YourStory has also published the pocketbook ‘Proverbs and Quotes for Entrepreneurs: A World of Inspiration for Startups’ as a creative and motivational guide for innovators (downloadable as apps here: Apple, Android).

Edited by Suman Singh