Rise of the next breed of entrepreneurs in smaller cities and towns of India

Startup activity is on the rise in Tier II and III cities of India, driven by different motivations and factors. On National Startup Day, YourStory examines the growth of startups in Bharat and the promising trends going forward.

Straight after graduation, Vishal Virani set up Corsuscate Solutions, an IT consultancy, with his friend Rahul Shingala in Surat.

While running the firm, Vishal and Rahul realised that developers spent a significant amount of time on mundane and repetitive tasks. This gave birth to the idea of a programming platform for developers to convert their designs into code for mobile and web applications. In April 2021, the duo set up , a SaaS startup, again in the city of Surat.

Why Surat and not any of the metropolitan cities that are the hubs of SaaS (software-as-a-service)?

Vishal has an emotional connection with Surat, where his father had lost almost everything after his business made losses. He was studying in class eight then.

“Since then, I’ve had this emotional element that I have to build something from the same place my father lost everything,” says Vishal, Co-founder and CEO of Dhiwise.

Mubeen Masudi had a different motivation to establish his startup in Srinagar.

After graduating from IIT Bombay in 2011, Mubeen could have chosen to start up anywhere in the country, but he chose to go back to his hometown in Srinagar to set up his firm Rise.

The dearth of opportunities in Srinagar prompted Mubeen to establish Rise, which provides courses and mentorship for Kashmiri students to improve their chances of getting into prestigious educational institutions in India and abroad.

The stories of founders like Vishal and Mubeen are testimony to the passion and courage of young India to start up on their own in the smaller cities of the country.

Startup activity in small towns

Startup activity is on the rise in the smaller cities and towns of India, driven by different motivations and factors.

Over 38,250 startups were recognised by the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT) in Tier II and Tier III cities, as of June 30, 2022—of a total of 72,993 recognised startups in India.

Cities and towns are classified based on housing rent allowance slabs. Mumbai, Delhi, Chennai, Kolkata, Bangalore, Hyderabad, Ahmedabad and Pune are considered Tier I cities and the remaining are categorised as belonging to Tier II or III.

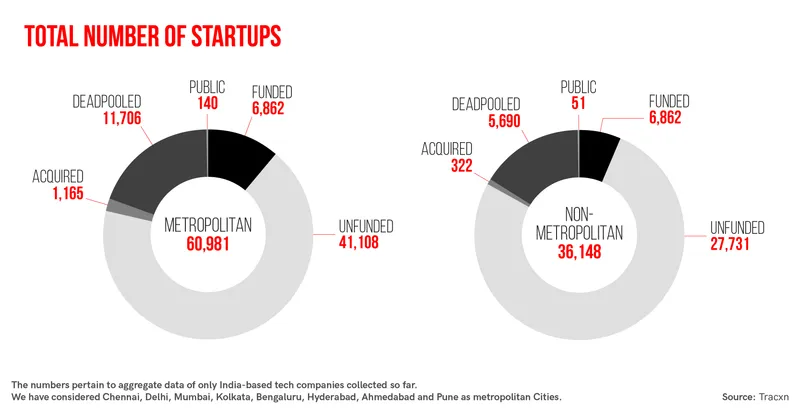

As of January 12, 2022, there were 36,148 startups in non-metros compared to 60,981 in metro cities, according to data from Tracxn.

Factors such as lower real estate costs, improved internet penetration, and supportive government policies are aiding the growth of startups in small towns and cities.

“Small towns and cities are shedding the historical perception of being difficult places to operate a business from,” says Pooja Mehta, Chief Investment Officer, JITO Angel Network, sector-agnostic, early-stage angel network.

Tier II and III cities now offer improved infrastructure at lower costs compared to Tier I cities. The remote-first approach along with the rise of managed office and co-working spaces have led to the mushrooming of startups in sectors such as healthcare, agritech, socialtech, and ruraltech.

“We have seen startups relocating to smaller cities due to lower costs of living, increased internet penetration and the availability of semi-skilled talent,” says Umesh Uttamchandani, Co-founder and Chief Growth Officer, DevX Venture Fund, which primarily invests in early-stage tech B2B startups.

Numbers at a glance

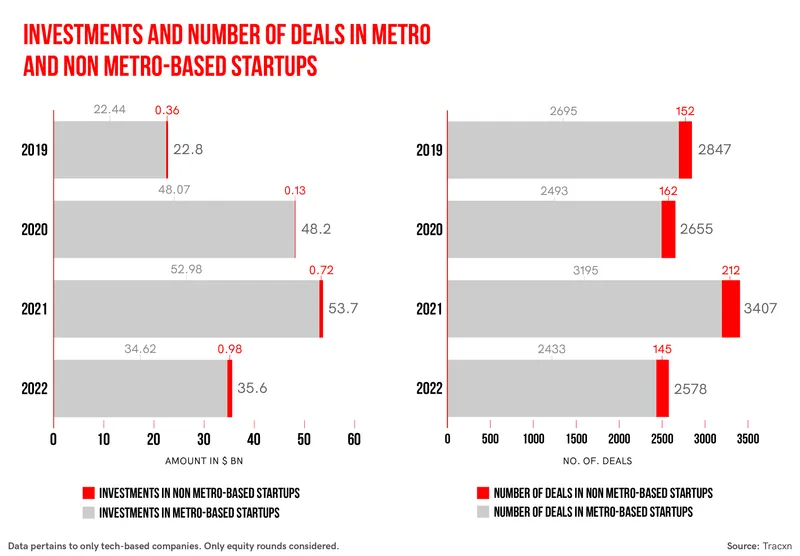

On the flip side, although non-metros today host a significant number of startups, they received just 1.4% of the cumulative funding between 2019 and 2022, according to Tracxn. Tier II and III cities accounted for less than 6% of the aggregate funding deals in the same period.

This has forced some founders to shift base to Bengaluru, a preferred destination for raising funds, says Karteek Pulapaka, Co-founder & Partner, Java Capital, a pre-seed/seed fund based in Bengaluru.

Interestingly, despite not attracting a big share of funding, the average deal size in non-metro startups has nearly tripled from $2.4 million in 2019 to $6.8 million in 2022. In comparison, the average deal size in startups based in the top eight cities has increased by over 72% from $8 million in 2019 to $13.8 million in 2022, as per Tracxn data.

There’s not a vast difference between the percentage of startups that wound up operations in the metro cities (19.2%) and the smaller towns (15.7%), according to aggregate data collected by Tracxn so far–perhaps indicating that the chances of a startup surviving are almost the same despite the former attracting higher investor interest.

Fifty-one startups from the lanes of India’s small towns have gone public, pointing to their potential for growth, while 140 startups from metros have taken the IPO route.

Only one small-town startup has joined the unicorn club so far—Jaipur-based CarDekho, an autotech firm.

RazorPay, which is now based in Bengaluru, had a humble beginning in the same city of Rajasthan. It entered the unicorn club after it raised $100 million in Series D in October 2020.

Challenges of bagging funding

Despite the high potential of startups in smaller towns, it is not very easy for founders to attract investments for their ventures for various reasons.

In the case of Vishal and Rahul of Dhiwise, it was difficult for them to convince investors that they could build a development tool from Surat, a town known for its diamond and textile industries. In fact, the founders were rejected by 40 VCs, before they closed their seed funding round of $2.5 million from India Quotient and Dholakia Ventures in January last year.

Vishal says one of the main reasons why they were rejected was the perception that, since they were based in Surat, they did not have “star developers” in their team or a good understanding of the startup ecosystem, “despite having a decent number of users and a ready product”.

Mubeen of Rise was well aware of the challenges of getting funded, which is why he didn’t even approach investors, in spite of having access to a VC investor circle and his IIT background.

“All institutional funding for a place like Kashmir was out of question,” he says. “So, we focused on making the company a for-profit, social-impact creating institution. We bootstrapped our way out.”

Fortunately, things on the investment front are slowly but surely changing. Today, incubation firms and angel networks are increasingly working with startups in small towns to guide them through the early stages and help them with funding opportunities.

For instance, JITO provides mentorship, resources, IT infrastructure support, and legal and tax advisory and connects founders with the right investors. So far, the JITO group has invested in five companies in Tier II markets.

Mohan K, angel investor and Co-founder & CEO of Chennai-based payment aggregator IppoPay, has invested around Rs 3 crore in 24 startups in the last one year. Some of the funding has gone towards startups in smaller places, such as Trichy-based Frigate.

Bhubaneswar-based Milk Mantra says it is the first-VC backed dairy foods startup in India. It has raised around $32.7 million from 35 investors, nine of which are institutional, according to Tracxn.

Promising trends

What is heartening to note is that startups in smaller cities are solving local problems that were not looked at by larger companies.

“The structural deficiencies in the lower tier cities and the problems they lead to are often so peculiar that it is very difficult for outsiders to build for them,” points out Pearl Agarwal, Founder & Managing Director, Eximius Ventures, a Gurugram-based micro venture fund. “Therefore, it is optimal if people who are close to the epicentre of the problem can create solutions that resolve these issues.”

For instance, GFF Innovations, a startup incubated by Chandigarh University, has come up with a machine called Moksh that collects crop stubble and turns it into a biofuel. Patna-based Husk Power Systems converts agricultural waste, mainly rice husks that are typically left to rot, into gas that powers an off-the-shelf turbine to generate electricity.

Another promising trend is the rising influence of e-commerce and social media platforms in Tier II and III markets, which has led to the emergence of a huge consumer base for startups to leverage.

According to a report by Boston Consulting Group, 54% of online shoppers in India will hail from rural areas by 2030, and they will account for 24% of online retail spending.

“We have observed a growing ecosystem of D2C (direct-to-consumer) startups in Tier II cities,” says Pushkar Singh, Partner at Tremis Capital, an early-stage investment firm.

Edtech startups too are eyeing Tier II and III cities, according to Pushkar, as a vast number of students here lack access to proper educational resources that can enhance their career prospects.

Lending infrastructure, cold chain logistics, healthcare, agritech, drone technology, rural logistics, and social tech are the other emerging areas in small towns, according to investors YourStory spoke to.

With investor interest slowly picking up, founders are optimistic about the future of startups in India’s small towns.

Vishal is confident that Dhiwise would shine in the diamond city of Gujarat, while Mubeen is hopeful of “climbing mountains”, after having created a dent in the lives of Kashmiri students.

Edited by Swetha Kannan