A peek into the operation and challenges of the Indian dairy sector with Stellapps CEO Ranjith Mukundan

In a conversation with SocialStory, Ranjith Mukundan, CEO and Co-founder of Stellapps, talks about building traceability in the dairy industry, impediments faced by small and marginal dairy farmers and the significance of moving towards sustainable animal husbandry practices.

Milk and its many derivatives are recognised as an integral and almost irreplaceable part of our daily intake. Be it our morning cup of tea or coffee or the chocolate ice-cream we indulge in after a busy day’s work, dairy products are elemental to our diets.

India is the world’s largest producer of milk, contributing a whopping 19 percent of the global production. According to the Animal Husbandry Statistics Division, Government of India, the dairy sector churned out over 187 million tonnes of milk in 2018-19. This was made possible by the 75 million milk-producing households in the country.

India is the largest producer of milk in the world.

But despite being the dairy capital of the world, India, on an average, produces only 3.85 kilograms of milk per day as compared to more advanced nations. The UK, the US and Israel produce 25.6, 32.8 and 38.6 kgs respectively. Some of the reasons for this low yield are lack of education and training, inadequate veterinary healthcare facilities, supply chain inefficiencies as well as improper rearing, breeding, and nutrition practices among others.

Ranjith Mukundan, CEO and Co-founder of , has been at the forefront of leveraging technology to bridge the gaps within the dairy sector. After working with Wipro Technologies as its Global Head of Telecom Value Added Applications (VAS) Practice and Head of Centre of Excellence (CoE), Ranjith established the startup to digitise the production and supply of milk end-to-end.

In a conversation with SocialStory, Ranjith talks about building traceability in the dairy industry, challenges faced by small and marginal dairy farmers, and the importance of moving towards sustainable animal husbandry practices.

Ranjith Mukundan, CEO and Co-founder of Stellapps.

SocialStory (SS): Can you give us an overview of the dairy sector in India as you have witnessed over the years?

Ranjith Mukundan (RM): India has the highest level of milk production in the world. Presently, it forms around 4.2 percent of the gross domestic product. However, the entire sector is highly fragmented. Around three-fourths of the dairy farmers in the country are unorganised and they own two or three cows each. Hence, most of them have yet not been able to participate in modern processes or have been able to inculcate technology.

Furthermore, the organised sector in itself is growing at a rapid 20 percent year-on-year. With renowned companies like Amul, Mother Dairy, Nandini, and Kwality Limited continuously expanding their presence, the commercial sales and distribution of milk and its products are expected to grow. Since a lot of farmers still do not have steady market linkages, there is an immense potential that is left untapped.

Majority of India's diary industry comprises of unorganised small and marginal farmers.

SS: Some undercover studies have shown ill practices and methods being implemented while raising cattle. What do you have to say about that?

RM: It is very important to understand as to what goes into the glass of milk that people consume every morning. Organisations such as Animal Equality and the Federation of Indian Animal Protection Organisations (FIAPO) have conducted investigations across many dairy farms in India and uncovered farmers applying inappropriate means to handle cattle. Some of the common malpractices that I have heard about are injecting oxytocin in lactating cows, feeding low-quality fodder, using unsterile equipment to artificially inseminate cows, failure to provide timely veterinary care, and other ill-conceived breeding and nutritional methods.

This boils down to the lack of awareness when it comes to scientific and healthy animal husbandry practices among small and marginal farmers. So, to put an end to this, dairy farmers need to be educated and trained.

Additionally, the organised sector has to develop a system to incentivise farmers who produce good quality milk. This will, in turn, motivate or push the farmers to carry out healthy farming practices.

A lot of farmers do not have access to financial services and credit.

SS: What are some of the challenges that small and marginal dairy farmers deal with today?

RM: Small dairy farmers barely have access to financial services. The non-availability of credit facilities is a huge roadblock for them, especially when they want to expand their operations or upgrade infrastructure. India hasn’t yet completely opened up avenues for obtaining funds at competitive rates with a comfortable payback period.

Another challenge is regarding obtaining insurance for the cattle. Many farmers have suffered losses due to natural calamities like landslides and floods. Though the central government (NABARD) and the State Disaster Relief Funds are offering insurance covers for animals owned by these farmers, the implementation has not taken off on a large scale. Lack of awareness among farmers concerning purchasing insurance, passive participation from insurance companies, and livestock insurance not being made mandatory could be the root cause for this.

Much like farmers who cultivate crops, dairy farmers are not well-compensated for their produce as well. Therefore, digitising payments in such a way that it can directly reach the dairy farmers can help eliminate middlemen and boost their income. A system to ensure direct benefit transfer (DBT) is what we need.

SS: How efficient is the infrastructure for cold storage? Do we need a better capacity?

RM: Most of the cold storage facilities in the country, especially in rural areas, are located about three to four hours away from dairy farms. A lot of the milk produced either deteriorates in quality by the time it reaches the consumers or simply goes to waste. Right now, India has a total cold storage capacity which is far less than what is required.

Besides, remote regions do not have three-phased electricity grids to support cold storage facilities. The government and all the stakeholders have to start looking at alternate solutions such as establishing common storage centres or miniature chilling stations with smaller capacities.

Approximately two billion kilowatts of electricity per hour is being used to chill dairy products today. And, 75 percent of this is fuelled by diesel, which results in significant carbon and greenhouse gas emissions. Shifting to renewable energy to chill milk and optimising chilling equipment are imperative to ensuring minimal environmental damage. Solar electrification is one of the best options that I can think of.

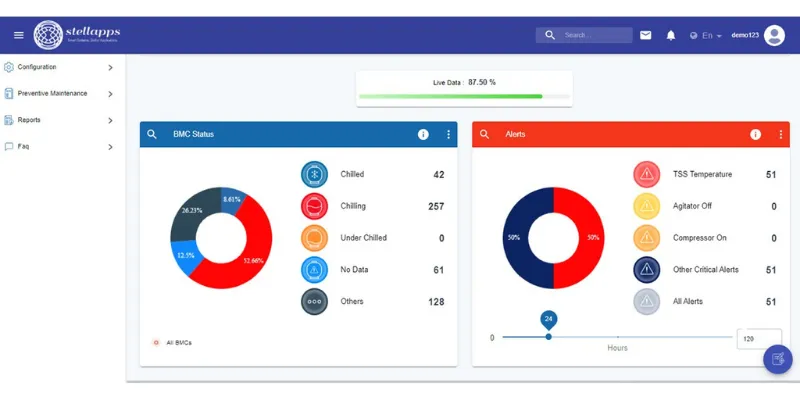

A screenshot the Stellapps page showing data on chilling milk using cold storages.

SS: Many startups are attempting to bridge the supply chain inefficiencies within the dairy sector with the help of technology. What are the opportunities for them?

RM: Startups need to remember that not all farmers have access to smartphones and internet connectivity, though the penetration has shot up in the last few years. Building apps to monitor animal diseases, providing care, and testing quality will definitely be useful. However, coming up with the right hardware to complement this is equally essential to enable operational touchpoints. Well, I have observed a lot of startups focusing on software and ignoring the hardware aspect.

To give an example, at Stellapps, we have been leveraging advanced analytics and artificial intelligence through our full-stack IoT platform to enable the dairy ecosystem to make data-driven decisions.

The startup acquires data through sensors that are embedded in animal wearables (mooON device), milk chilling equipment (ConTrak), and milk procurement peripherals (smartAMCU/smartCC). This is then made accessible on mobile apps to assist stakeholders in improving supply chain efficiency, preventing adulteration, and enabling traceability.

I also believe that the role of technology in the dairy industry is that of an enabler. It is not everything. One startup cannot solve all the pain points. Adopting an ecosystem approach and resorting to collaboration is key.

Ranjith sees technology as an enabler in the world of dairy farming.

SS: What more do you think the government can do to boost dairy production in India and improve the livelihoods of farmers?

RM: The government can bring about sweeping transformations in this sector by directing its energy on farm economics, equipping farmers to increase the yield from cattle and shifting from a supply forward to demand backward market approach.

Edited by Kanishk Singh