‘There’s something about Jerusalem you can’t turn away from’: the 3,000-year-old city is history in motion

An hour’s drive from Tel Aviv, Jerusalem is an old, sombre, sepia-tinted land that takes you back to about a dozen historical empires and several hundred years

“Ten measures of beauty descended on the world, nine were taken by Jerusalem, one by the rest of the world.”

— The Talmud (primary source of Jewish religious law and theology)

Many eminent travellers, including the great Mark Twain, have fawned over Jerusalem’s ‘beauty’. It is a strikingly beautiful city, after all. But it might be a disservice to call it just that. Because much like its 3,000-year-old multi-cultural history that greets you at every lane, alley, and ‘beautiful’ bend in the road, Jerusalem cannot - and should not - be contained in a single word or phrase.

Tel Aviv | Image: Shutterstock

The city is an hour’s drive from Israel’s bustling cosmopolitan capital Tel Aviv. But, a lot changes in that one hour as you drive out of a quintessential first-world city, and cross vast stretches of the arid, yellow Judean Desert… to enter an old, sombre, sepia-tinted land that dates back a few thousand years.

In just 60 minutes, you traverse a few centuries, about a dozen historical empires, and several topographical landmarks.

But, despite the unmistakable religious and socio-cultural allure of Jerusalem, some locals in Tel Aviv often advise ‘foreigners’ against visiting it, especially during a festival or protest - both rather common occurrences, sadly.

On the eve of Eid-ul-Fitr, a gregarious fifty-something cabbie in the capital offered us some ‘friendly’ advice that sounded pretty much like a warning.

“Go to the port, go to the markets, go to Yafo,” he said. “Why go to Jerusalem tomorrow?”

“Why not?” we asked, genuinely curious.

“Not good, not safe… look at what they did to me,” he said, pointing at a deep scar on his forehead. “They come for prayers, and they throw stones. They have knives.”

Cue a nervous pause.

“Jerusalem, not safe. Old City, not safe,” he thundered away.

While this did nothing to prevent a bunch of overzealous Indians from trekking to, what many call “The Holy Land”, it did capture the volatility of the place.

History might remember Jerusalem as the birthplace of the world’s three major religions - Christianity, Judaism, and Islam - but in the 21st century, the city has been caught in an acute, long-lasting, ethno-political conflict between Israel and Palestine.

Unsurprisingly, every nook and cranny of it bears witness to this pain and uncertainty. The soil is dry, the trees are unkempt, and the houses vacant. You can smell the unrest - mixed with the fragrance of flowers, candles, and coffee.

You can smell death too that engulfs Jerusalem Old City - particularly in the Christian and Armenian Quarters - where 2,000-year old cemeteries, tombs, and burial caves seem to stare right through you.

Jerusalem Old City | | Image: Shutterstock

Guides will tell you that the Arabs and Jews are fighting for the possession of East Jerusalem - among the most affected areas - and that bombing and shelling have devastated buildings and claimed thousands of innocent lives just a few feet away. You’d be asked to walk in a group, beware of suspicious behaviour on the streets, take a step back even if you spot a ‘toy gun’ in the hands of street children.

Jerusalem is replete with history and culture | Image: Sohini Mitter

You’d also be shown a line or a gate or an area that cannot be trespassed, for what lies beyond is… unpleasant and unfortunate.

And yet, year after year, hundreds of thousands of travellers, mostly ethnic Christians from across the world, travel to Jerusalem. They climb its mountainous roads to offer a small prayer, light a faint candle, remember the dead, and mourn the end of peace and humanity.

The Wailing Wall in Jerusalem | Image: Shutterstock

At the Kotel or Wailing Wall, one of the most important landmarks here, pilgrims knock their heads on a large limestone wall and leave notes for their loved ones who couldn’t make it here. Their voices tremble and knees creak, but their faith is still and gripping. It almost hurts to see them, but you just cannot look away.

That is the very essence of Jerusalem: a feeling of intense melancholy that you simply cannot escape. One that haunts you long after you’ve left the place.

Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk would have called it ‘huzun’. If Istanbul is characterised by ‘huzun’, like Pamuk says, then Jerusalem has double of that. And, more.

You encounter ‘huzun’ once again at The Basilica of Agony. A fourth century church that has undergone several renovations down the centuries, it enshrines a place where Jesus is said to have prayed one last time before his crucifixion. The church is a sprawling exponent of Byzantine architecture, but what you’d probably take back as an enduring memory is a mural of Jesus - hunched over his knees right before his arrest.

It is an image that will remind you that Jerusalem is also a city of atrocities.

Church of Our Lady of Sorrows | Image: Shutterstock

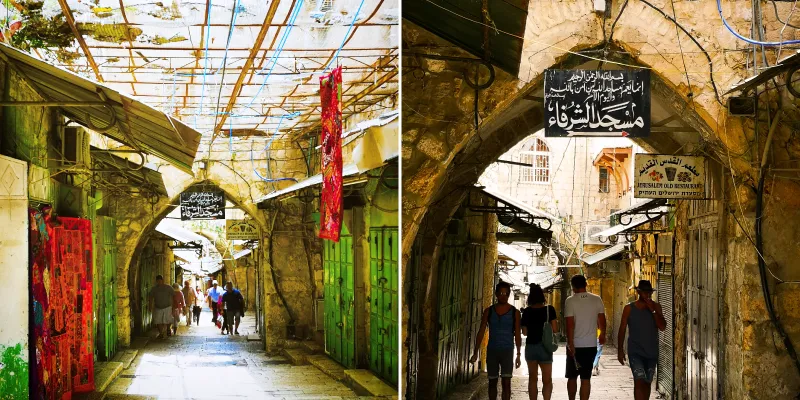

You walk a little further through the congested-but-colourful Arab Market, gorgeously lit up for Eid, right till the end of the Muslim Quarter to reach the Church of Our Lady of Sorrows. This place, also known as the Fourth Station, commemorates Jesus’ last meeting with his mother, Mary, on the way to his crucifixion.

The Arab Market | Image: Sohini Mitter

At present, an Armenian Catholic Church, erected in the 1880s, stands here, that has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage site. The elegance or perhaps the significance of the church will dwarf you, and even make you weep a little.

Mount of Olives | Image: Shutterstock

That is another of Jerusalem’s traits. It drains you - physically, emotionally.

The June heat is sapping. Add to that, the morbid history of the place. You crave for a breather, and head to an unassuming eatery outside Fourth Station. Local food beckons, you would think? But what strikes you at the outset are disturbing paintings of the Holocaust hung on the walls of a nameless, faceless Armenian restaurant.

Your steps are measured as you soak in the surroundings. The air is heavy with the smell of olive oil, hummus, and historical loss.

You’re informed by a local, “Jewish families in Israel are encouraged to speak of the Holocaust. These paintings are hung in public places to remind people that ‘it’ happened and that ‘it’ never happens again.”

Gulp.

Jerusalem can also be an unending history lesson. And, you have got to turn the page.

Or as British-American author Pico Iyer puts it, “I would never call Jerusalem beautiful or comfortable or consoling. But there’s something about it that you can’t turn away from.”