Meet Jamie Alter, the white man with an Indian passport and heart

Jamie Alter, son of Padma Shri Tom Alter, wears many hats and is a pucca desi despite his American heritage.

The first time I met Jamie Alter I did not know who he was. It was at a morning editorial meeting at India’s largest media conglomerate where we were colleagues. It’s not unusual for Indian newsrooms to have expats. So, it was not all that surprising that there was a lone Caucasian man in the conference room.

But I was taken aback when Jamie started speaking in chaste Hindi during the course of the meeting. It only made sense later when I was told, he is Tom Alter’s son.

Jamie Alter

The late Tom Alter of course needs no introduction and has been a household name in India. He was awarded the Padma Shri, India’s fourth highest civilian honour, in 2008 for his contributions in the field of arts and cinema.

Jamie wears many hats - sports journalist, actor, YouTuber. In this interview with YS Weekender, he talks about his unique life, his Indian identity, growing up as Tom Alter’s son and his latest brush with acting through Amazon Prime Video’s web series Afsos.

(Edited excerpts below)

YSWeekender: White guy with an Indian passport. There would have been some interesting experiences at Indian and other immigration checks?

Jamie Alter: One time I was flying from Bangalore to London, in 2008. At the immigration counter, the airport official whom I handed my passport doubted the validity of it and detained me for some time before finally letting me go, after another official intervened.

Another time, I was returning from a cricket tour in Sri Lanka. At immigration, the Sri Lankan official behind the desk looked at my Indian passport and gave it back to me, asking instead for my “real passport”. It took some persuasion on my part to convince him it was real.

YSW: Sports journalist, accidental ‘Tinku Jiya’ (a character Jamie portrays on Times Group’s satire web show ‘Fake it India’). Now YouTuber and web series actor (Afsos on Amazon Prime Video). How did it all happen?

JA: I chose sports journalism in 2005, while disillusioned with my job in an insurance company called SunLife Financial outside Boston and also homesick for India. In January 2005 I saw an online advertisement for an opening for a cricket writer’s job at what was then Wisden Cricinfo and fast forward to October I had got the job.

Fifteen years later, after covering multiple Cricket World Cups and other sporting events across platforms like Cricinfo, Cricbuzz, Cricketnext and the Times of India (TOI), here I am creating content for YouTube and acting in a web series for Amazon Prime Video.

Fake It India happened because the creator of that satirical show, Neeraj Badhwar, and I were colleagues at TOI.

He asked me to appear on an episode, gave me the name Tinku Jiya and convinced me that people would lap it up.

Afsos happened because the writers of the dark comedy were looking for a white man who could speak proper Hindi. One thing led to another and now I am in Afsos as Dr Goldfish.

Jamie as Tinku Jiya on Times Group's satire web show Fake It India

YSW: Is mainstream Bollywood a possibility?

JA: Afsos was a rare project because the character spoke Hindi and was Indian. I don’t know what kinds of roles could possibly come my way. But I am game for Bollywood, if it happens.

YSW: Your forefathers came to India as Christian missionaries and decided to stay back. Tell us about your family’s association with India.

JA: My paternal great grandfather came to India – or what is now Pakistan – in 1916. My paternal grandfather was born in Sialkot, all three of his children in India, and I was born in India. My paternal grandfather was a theologist and pastor who preached across north India and opened an ashram in Rajpur, outside of Dehradun. My father and his two elder siblings studied at Woodstock School in Mussoorie, where some 32-odd Alters have studied.

Each person went back to the US after their postings were completed. Only my father, while studying at Yale University during the time the Vietnam War broke out, decided to return to India because he could not identify with most Americans there.

He realised he was Indian at heart.

Of all the Alters – and there are many – only two have Indian passports: my father and I.

YSW: Tell us about your fascination with 90s Bollywood.

JA: I grew up in India of the 1980s and 1990s, and that too in the same house as a Hindi film actor. So, from a young age there were LPs (vinyl records also known as Long Plays) and cassettes of Hindi film music around me, there were script readings and play rehearsals and actors coming and going.

Then of course I visited my father on the sets of movies and TV serials. Then I learned Hindi, began watching Hindi films. So, it was inevitable. Personal choices changed with the years – Amitabh Bachchan to Jackie Shroff to Aamir Khan – and the 90s were pivotal.

I can tell you when it all got serious: 1990, when Aashiqui released.

My father had taken the family to a screening of the film soon before its release. I was nine. Not long after, the songs of Aashiqui became a rage and then the film released. To see the impact of that film and in particular the songs had on so much of this country, and to suddenly see my father every Wednesday on Chitrahaar when ‘Main Duniya Bhula Doonga’ was a surreal experience. That was – is, rather – a fantastic album and Kumar Sanu has been a constant in my life since 1990.

I think when one looks back, their teenage years are the most definitive. And for me, being in Bombay and around the sets and almost every Friday watching a new Hindi film in the theatres from the ages of 12 to 15 did it all.

A young Jamie with his father on set with actors Raghubir Yadav and Pooja Bhatt

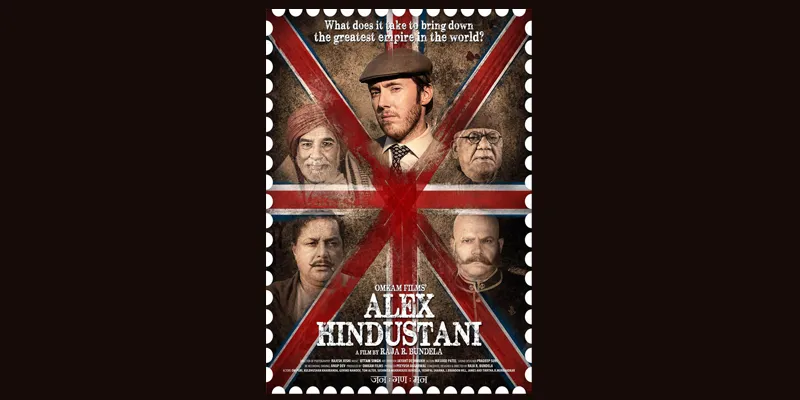

YSW: Afsos is not your first acting gig. You acted with your father in Alex Hindustani, tell us about that.

JA: That was a film he was far keener than I was. I played my father’s son in the film.

I was a wreck on that set, not sure of what I was doing. But it was great fun, and I made some good friendships on the sets.

The movie has never been released. To make a film is a bloody tough job and I know how many people put a lot into that film, so for their sake I do hope Alex Hindustani sees the light of day.

Much before Alex Hindustani, I played my father in a flashback in his award-winning art film, Ocean of an Old Man. I had about five or six scenes, of which none made it to the final version. Soon after Alex Hindustani, I again played my father in a flashback in a masala Hindi film, Life Ki Toh Lag Gayi.

I had one scene opposite Jackie Shroff, which was deleted down to barely five seconds in the final cut.

A poster of Alex Hindustani

YSW: Your father has left behind a rich legacy. Is it a boon or a bane having such a famous figure as a father?

JA: It is a legacy that I have to be aware of at all times, which is not easy.

I am nowhere near my father’s level as an actor or human being.

He did not drink or smoke, exercised regularly, was painfully passionate about his craft, was fiercely dedicated to this country and believed in a certain India which sadly we are seeing eroded on different levels today. He had time for everyone, was wholly supportive of so many actors, writers, directors, producers and technicians in his industry and he could drop whatever he was doing at any time of day or night to help someone.

I am not that person in entirety. Should I strive to be? I don’t think so.

I have my own identity, yet I am aware that without my father I would be little. I have gained from his success, I do not deny that.

I am proud of his success. I can only admire and respect the hard work and pain he put in across his forty-plus years as an actor. I never had that drive, that passion or that junoon for making acting my profession.

YSW: Tell us about your growing up years in Mumbai and Mussoorie.

JA: Two different worlds. I am fortunate to have experienced both. Bombay in the early 80s was wonderful. Then we shifted to Mussoorie from 1986 to 1991. The wonder years, as I call them. Nature, blue sky, no pollution, rain and mist and spring and snow.

We had so much space to run around. I rode bicycles, climbed trees, jumped down the hill and scraped my way back up, I made long-lasting friendships. Those were wonderful years and I am blessed to still have a home in Landour. (Landour is a small cantonment town contiguous with Mussoorie)

Young Jamie with his father Tom Alter

YSW: As a kid, how did you feel seeing your father in negative roles?

JA: I actually don’t remember watching any role and thinking ‘oh that’s a bad man’. The first instance of his screen role impacting me was when I saw him get killed in that chilling church massacre scene in Shyam Benegal’s Junoon, at the hands of Naseeruddin Shah.

Later, when Naseer came over to our flat for a rehearsal of one of Motley’s (a theatre group) plays, I saw him walk in the front door and burst out crying because he was the man who had killed my father.

I was five or six. It took some convincing from my parents that it had happened in a movie.

YSW: Most memorable role of your father?

JA: The role from a young age that impacted me was my father’s in a DD (Doordarshan) show called Jugalbandi.

It was modelled on Miami Vice and my father played this cool cop who wore jeans, dark shirts, boots and Ray Bans.

He had a holster and gun and jumped from one moving car to another and bashed up five or six bad guys. It was India’s first buddy-cop show, and starred Radha Seth as my father’s partner and Girish Karnad as their boss. Ahead of its time, that show.

His role of the hostel warden in Aashiqui earned him a lot of popularity. It was his longest screen role, so that was fun to see even though the character was not nice.

He was very good as Lord Mountbatten in Ketan Mehta’s Sardar. And though it was a brief role, the vital arc his character Musa played in Parinda is one I cherish.

YSW: Tell us about your experiences in the US, where you lived for six years?

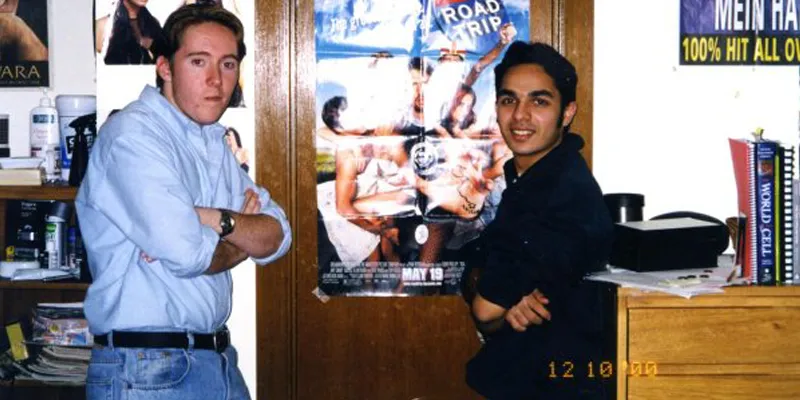

JA: I completed three and a half years of college (BA is Political Science from the College of Wooster) and then two and a half working. My college years were fun.

As soon as I landed on campus I had Indians asking me if I was Tom Alter’s son. There was Hindi music playing in my dormitory corridor and Indians and Pakistanis were getting along like old friends and there was tennis-ball cricket being played.

Within weeks I was on the college’s student council as a South Asian representative.

Jamie with an Indian friend inside his university room in Ohio

ALSO READ

YSW: You also had an interesting encounter with a Sikh shopkeeper in the US once. Tell us about that.

JA: This happened during a drive from New Jersey to Ohio in the winter of 2003. Somewhere in the dead of night I had to refill fuel and coffee. This was in the middle of a long stretch in Pennsylvania. It was snowing pretty heavily. I saw a sign for gas and refreshments and took the exit.

I was driving down a side road and there was this solitary gas station. Imagine the scene: snow fall, 3 am, not a soul to be seen, a sign flapping in the wind. Like a Hollywood horror film.

I pulled up next to the filling station, and ran straight indoors. I opened the door and there seated behind the counter, catching a few winks, was a sardarji! I don’t know what happened next but I just blurted out: ‘Oye sardarji chai pila do, vaddi tandh hai bahar!’ and the man’s eyes opened wide. I think he didn’t realise whether he was awake or dreaming.

Imagine his shock when in the middle of the night, out of a near blizzard, a white guy enters his gas station and asks for tea – in Punjabi!

Anyway, we had a lovely chat, swapping stories, and he didn’t let me pay for the coffee.

Edited by Asha Chowdary