My tryst with Nokia: Customer, Competitor, Employee

I read the news about the Nokia acquisition by Microsoft with a sense of disbelief, like many others. It was not totally unexpected, given the path Nokia has been over the last few years, but what was startling was that it actually happened.

Like millions of Indians, my love affair with mobiles began with a Nokia. The first mobile I owned way back in 2003 was the Nokia 2100 - affectionately nicknamed ‘tubelight’ for the way the keypad lit up.

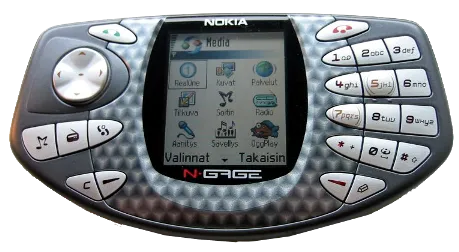

Most people I knew also had other Nokia phones, ranging from the 2300 (venn diagram) to the N-gage, one of the first gaming mobile phones.

Nokia as competitor

I joined Motorola in the product marketing arm in 2007, and realized what a formidable competitor Nokia was.

Nokia’s advertising was legendary. No one will forget the sheer ruggedness of the Nokia 1100, ably demonstrated in ads by showing the phone dangling below a truck bumper with a tagline ‘Made for India’. What a powerful marketing message it was!

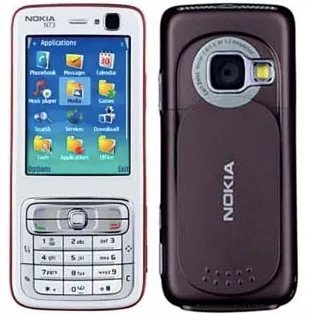

Nokia was also a leader when it came to envisaging converged devices. Many Indians will fondly remember the N73, a device that let you listen to music, take photos and videos, and browse content.

Motorola’s industrial design was still an advantage then – the Razr, Razr 2, E7, etc. were sleek and a contrast to the bulky Nokia devices. But with the Nokia 5310 Express music phone, Nokia showed that it could compete even in this field.

Nokia – the distribution genius

Today, not many remember the sway Nokia held over the retail market in India. For most Indians, mobile phones meant Nokia. Nokia’s strategy seemed flawless – it had targeted advertising to appeal to Indian consumers; had a range of devices for consumers to choose from; a broad distribution reach to ensure that when people walked into the store, they found their Nokia; even inventory policies to ensure that they could sell more devices.

Across consumer industries in India, distribution strategy plays a key role to get your product in the hands of consumers.

Say Nokia or Motorola had to launch a new phone in India. They would assemble the device in their factories, load software and Indian customization settings like language packs, wallpapers, ringtones, GPRS settings, etc. After quality testing and packaging, they would then ship the phones to a national or regional distributor.

The distributor is a key partner in the process. He would pick up stock at a distributor price, usually on credit, and arrange for stock to be warehoused. His team, along with the company sales team would then work on selling stock to regional distributors who handle smaller territories, or large retail chains. The regional distributors would in turn sell stock to small and big retailers from where consumers could pick up their devices.

This process worked closely with the company sales policies – pricing at various tiers in the chain, sales incentives, and marketing – collateral/training across chain, selling in key value proposition, planning ATL (above-the-line) media campaigns in line with when devices would be available at stores, and BTL (below-the-line) marketing elements like brochures, dummy devices, etc.

Stock had to move through the channel smoothly for sales to tick. A number of things could affect this.

Say a company wanted to launch a new phone in India. There would be an internal portfolio team who planned global volume shipments and pricing. The local sales team would place their estimates at the start of the planning cycle. Closer to the actual launch, they would start selling-into the channel. This process usually meant talking about upcoming devices to the sales channel (and often gathering feedback on earlier devices and market conditions). Depending on the phone pricing and volumes, the sales team would get the distributors to ‘commit’ to certain volumes of devices they would pick up on the promise of support on marketing and incentives. Distributors would then sell into their channel by adding an agreed margin. This margin would cover their costs of storage and actual distribution, their own salaries and incentives, and the ‘risk’ they carried.

The ‘risk’ was twofold.

Mobile phones are notorious for the pace at which new models were launched, making earlier models obsolete, and the phenomenon of ‘price drops’.

Leaving aside Apple’s iPhone, think of every other phone you wanted to buy. At launch, the phone would be priced very close to the printed MRP, a strategy called market skimming to get early adopted to pick devices at a higher price points. Subsequently, as volumes grow, prices start declining, or consumers are offered freebies with the devices to grow the market for a device.

In an ideal situation, the mobile phone company would guess the correct price at which initial volumes were to be sold and plan for gradual price drops. However, many factors made this difficult.

One that we’re seeing now is the exchange rate. Most global companies have a minimum global selling price in dollars to ensure that phones roughly cost the same across markets (important to prevent arbitrage and gray market shipments). But due to currency fluctuations, fresh batches of stock could cost more than the previous lots.The second was aggressive pricing by competitors. If a competitor launched a new phone with similar specs but at a lower price, it upset the cycle. End consumer sales would dip as they shifted to a lower priced handset (say, consumers buying Micromax Canvas instead of a Samsung Galaxy Grand). Since the distributors and retailers already held significant inventory of the company phone on their books, slower sales meant longer cycles and more money locked in. Companies often responded with price cuts. But then, who bears the cost for the inventory already held in the channel? This is where the inventory price protection window came in.

Mobile companies would decide on a window when they would bear the cost of the price drops on channel inventory. Post this, the distributor or retailer would have the bear the cost. As a distributor, you negotiated as long a window as possible, as that would give you time to exhaust stocks you held and not lose money. Companies would push back to keep this as short as possible so as to not absorb this cost on their books, promising more marketing support and offers in return.

Back in 2007-08, Nokia had perfected this art. Most of the leading players like Motorola, Samsung, LG, etc. had a 2-3 week inventory price protection window.

Nokia gave 1 week.

As a retailer, given how the market operated, I would try to exhaust my Nokia stocks fastest to not bear inventory losses due to price drops. Retailers have a huge influence on the purchase decision, as they are the ones who talk to consumers and can guide them (think of the time some retail agent said: “sir, yeh piece bik nahi raha hai, aap yeh doosra mobile try kijiye” or “sir, this piece is not selling well, why don’t you look at this other mobile”).

Retailers would live with this short limit because it was easier to convince consumers to buy Nokia. This meant Nokia had one stock turn in a week, and the money could be invested in buying fresh stock from Nokia.

End result: Nokia sold more mobiles due to this distribution strategy.

(Disclaimer – this is a largely simplified version that I have used for illustration purposes, based on my market experience with Motorola devices in 2007-08. Today’s scenarios could be different)

The digital pioneer

When Nokia announced the Ovi store, it seemed like this was the company to get us into the future. They offered a platform to sell music, games, customization skins and apps. On paper it was the perfect strategy. Analyzed as a competitor, they were in a hurry to establish their dominance in the new world – they bought Navteq, a navigation giant, and smaller companies that worked on digital advertising, customization, etc.

Motorola India tried launching a short-lived music offering called Motomusic to compete with this, but had to shut it down within a few months of launching it. Nokia was just too big to take on.

In 2009, I moved on from Motorola, just as the market was witnessing tectonic shifts. Android was growing rapidly, and Apple was beginning to expand beyond its initial tie-up with AT&T. The world was changing.

Nokia as employee

I joined Nokia in 2010 as a product manager, tasked with defining and managing location based services for the S40 platform, later rebranded as the Asha platform. Compared to the market stint I did earlier, this time, I worked on R&D and ideation.

I didn’t realize back then that this would also be amongst the most tumultuous periods in Nokia history.

The public struggles of Nokia are well documented – the steep loss of market share in emerging markets, the quarter-on-quarter losses, the litany of layoffs, the partnership with Microsoft, and now, the sale.

Emotionally, it was a cocktail of hope, faith and fear. Hope that we could regain prime position; faith in Nokia’s heritage of bouncing back against all odds; fear that the market was moving too fast for a large company like Nokia to react.

Looking back, there are many wistful if-only moments that I have about Nokia, but this is the not the place or time to talk about them.

Nokia is one of the most loved brands on the planet (which is I was surprised at the decision to not use the brand for smartphones post the buyout. Hey Microsoft, do you know how much people love and trust the brand even today in the emerging markets that the entire smartphone industry wants to break into?)

As an employee, it was also a great place to work. Nokia was a true global giant, and it was quite common to have people from multiple nationalities in the same team. The culture was respectful towards employees and mature: it trusted you to do the right thing. If you said a project would take a certain amount of time, your word would be respected. Of course, this also meant you could slack through your project, but meant your manager would try and coax you to be more efficient, rather than berate you.

If you wanted to learn, Nokia offered a fantastic vantage point to do so. Nokia had a rich history of ethnographic, consumer and usability research, sometimes a little too much, but this provided a great way of understanding how and why consumers behaved the way they did across different markets.

What I liked best in my time with Nokia was that there were so many experts in different fields, and most were willing to share their knowledge. I picked up a lot of my knowledge of mobile apps, UX design, consumer research and roadmap planning by interacting and learning from others.

I quit Nokia in Jan 2013 as part of a strategic realignment, but still followed its fortunes closely.

I hope Microsoft realizes value of the jewel they picked up, learn from it, and treat it with respect. If so, the Nokia spirit can change their fortunes.

Note: all views in this article are personal.