How Naveen Garg overcame poverty, an incurable disease and his first failed startup to become an entrepreneur

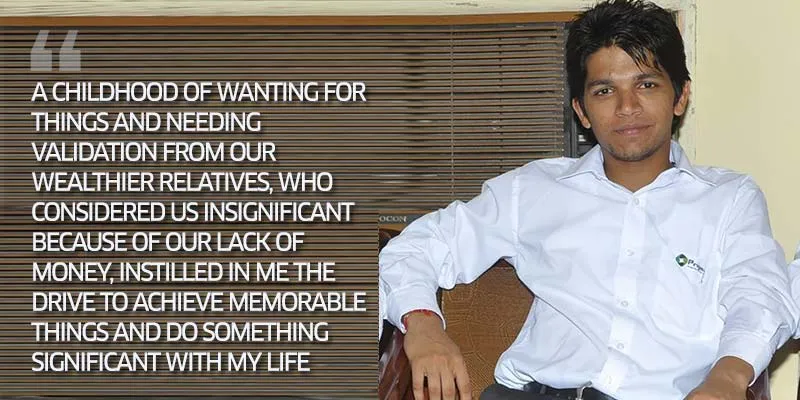

“Luckily I was not born with a silver spoon,” says Naveen Garg. “A childhood of wanting for things and needing validation from our wealthier relatives, who considered us insignificant because of our lack of money, instilled in me the drive to achieve memorable things and do something significant with my life.” Of course he does not need that validation now but is grateful to fate for having provided a springboard for ambition, irrespective of the negative place that it came from.

Naveen Garg was born in a small village in Punjab some 80 kilometres away from Bhatinda. His father was a postman and the family subsisted on his meagre salary. Naveen realized there were only two tickets to get out of the village and secure a better life- engineering or medicine. He chose the former. "Both my parents had studied up to 10th Standard. There was no one to give me proper guidance about my career. After I completed my 10th standard I knew I had to opt for science. But there were no schools or coaching centres in my village that offered the stream I loved. The nearest coaching centre was in Bhatinda, 80 kilometres away, and the fees they charged was enough to break the bank for us,” Naveen recalls.

Determined to do this for his son, his father borrowed the money and Naveen began the killing commute. The finances they managed was not enough to cover all the subjects. “I opted to get coached in physics and maths but had to leave out chemistry. That subject I taught myself.”

Naveen cracked the AIEEE(All India Engineering Entrance Examination) with a good rank and took on education loans to pay for his college fees. He says, “Given the poverty I grew up in, till that time my only dream had been to get in either IIT or NIT. That dream came true when I got admission in NIT Jalandhar in 2008.”

In 2010 he was diagnosed with muscular dystrophy, an incurable degenerative muscle disease. “During the second year of my undergraduate degree, I felt a weakness in my right knee. I figured it was due to bad food habits and ignored it. When it refused to go away, my roommate dragged me to a doctor. The doctor said it might be muscular dystrophy but asked me to tests done from AIIMS, New Delhi, for confirmation. It took two months for the report to come.

Those two months were agony. I googled the symptoms of muscular dystrophy and was broken to realize that they matched my condition. My brain realized the truth of the matter but my heart was not ready to accept it. I spent days and weeks feeling sorry for myself. But surely all my hard work and achievements until now could not have been for nothing? That thought kept me from giving up.”

By the time the report arrived, Naveen had schooled himself for positivity. “Allopathy calls this disease incurable. I call it In-curable: what you need to cure from inside.” To demystify his personal philosophy he says, “Doctors say cancer is incurable. But I have seen patients defy prognosis through sheer will power. I meditate and do yoga religiously. I have faith. And I don’t care if medical science reflects this or not but I feel improvements. I am going to cure myself from within.”

There is no middle ground here. It was necessary for Naveen to hold on to this attitude fiercely, else everything threatened to fall apart. Though he received the worst news of his life at NIT, it was also here that he met his future co-founders and friends for life and above all the idea which would later see him become an entrepreneur.

“The Prigma Edutech Services that we are looking at today did not come instantly or without suffering its share of risks. It took shape, tested by time, like any other natural phenomenon and still lots need to be done on it,” says Naveen. How it started is an anecdote of great fun. “It all started with a team comprised of crazy techies who wanted to do something that had never been done in our college before. So 15 of us came together and created a four wheeled off-road buggy with the innovation of ‘chassis sharing mechanism.' We also worked on building a racing car. For these projects we would work nights and days at a stretch. Our longest uninterrupted work period was 21 hours. It was the best time of our lives.”

Naveen soon felt the discrepancy between what they learnt in class and what they imbibed working on practical projects together. “During college life I observed there is a gap between actual academic studies and industrial or practical exposure. With the vision of bridging this gap, we started giving practical workshops on disassembly and assembly of pulsar 150 CC /Kinetic 110CC to our college peers to give a practical edge to their imaginations.”

Successful workshops at the college encouraged Naveen and team to conduct the biggest ever program in the history of NIT-Jalandhar. But things didn’t go as planned. “We decided to conduct a national level program titled ‘AutoFactory' with the help of X Company (name not disclosed). We would to disassemble two Maruti 800 to teach it’s functioning and designing to students. 260 pupils from all around India came for the event. Everything was set up. When the technical team of the X company reached our college, they refused to disassemble Maruti 800 (which they had agreed in MOU signed). Instead they asked us to open up a Pulsar engine.

This was very critical situation, what with 260 expectant students sitting before of us. No amount of discussion would budge the company representatives. The college authorities refused to intervene,” Naveen recalls.

With tensions mounting high, Naveen and his team decided to throw caution to the wind and carry out their demonstration independently. “After lots of discussion within team, we decided to go for disassembly on our own instead of raising issue on the MOU point. At that point we just wanted to get through the day without having a rioting audience on our hands. We by-passed the company, accepted the challenge and delivered the workshop on our own successfully.”

After Naveen graduated, he started working with Alstom India to gain some industry experience. His college mates Yash Pal and Amandeep Singh Mann, who were in their final year, started up a primitive version of PES. It was agreed that the rest of the core team would join the startup after spending a little more time at their current jobs. The friends were in constant touch over phone, discussing plans and ideating. Naveen candidly says, “This project was a complete failure. Not even a single student turned up for the program. There were problems at each end, from marketing to technical and finance to event management."

For a man dealing with a fatal incurable disease, this did not pose a disappointment. But Naveen was afraid that it might have deterred his co-founders. He was delighted to discover them spring back in action. “Yash analysed the whole situation thoroughly and came to several conclusions about our failure. They included lack of proper planning and a decent workforce, no initial funds and no proper strategy for marketing. Poor event management was the last nail in the coffin for that ill-fated startup.”

The team retreated, regrouped, planned and bided their time. Flash forward to December 2013 when they came together to start up a second time. The first thing they did was change the name from Prigma Edutek to Prigma Edutech Services. The majority of the core members decided to keep on working to maintain a financial backup while Yash and Aman were stationed at the helm. But everyone contributed on a part time basis. “That is how we started PES- with enthusiasm and trust,” says Naveen.

“The automotive industry is a booming sector in India which is attracting new entrepreneurs in designing, product development and manufacturing. It will need a huge skilled workforce in these areas. PES is providing practical training programs to students and professionals to fulfil this need,” says Naveen. By providing supplementary education which is as additive as it is absorbing, Naveen believes that PES provides that one thing which is sorely lacking in classroom training- excitement.

“In India we have many educated engineers, but not skilled engineers. Our target is to make them skilful so that they can start their own ventures or don’t face difficulties in getting good jobs.” They started up with a seed fund of less than 50,000 INR and whatever profit PES generates now goes right back into its betterment. Automobiles is the absolute initial chapter for PES. They have big plans of extension. Naveen says, “During this journey of entrepreneurship the one thing I learnt is that no idea is waste. Transforming an idea into a sustainable business depends upon the skill of the entrepreneur. The best part of this startup is that we are interacting with young minds and constantly learning new things, which is going to open many opportunities for PES to excel in the field of technology.”

While he is pouring his blood and sweat to grow his own startup, Naveen has one piece of advice for his peers. “Don’t think about building a successful company in one night. Concentrate on the services, not the expansion. The rest will follow.”