SMEs and e-commerce relationship status: frictional

Ahmedabad-based Suraj Vazirani has seen his fortunes change over the past five years after shifting from brick-and-mortar to online retail.

Suraj, who ran an electronics store in Gujarat for 12 years, had a false start in online retail when he started selling on eBay in 2008. Low sales made him wind down the online operations, but the buzz around e-commerce made him list again on eBay in 2010. Again the numbers were minuscule to begin with but this time Suraj stuck to it, launched his own e-commerce site and then joined other marketplaces like Flipkart and Snapdeal. The results were soon visible—Maniacstore, Suraj’s firm, earned revenue of Rs 7 crore in FY 2013, Rs 65 crore in FY 2014 and is targeting Rs 70 crore this fiscal.

“I never thought e-commerce would become this big. The Rs 7 crore-revenue we earned in FY 2013 itself seemed unbelievable,” said Suraj, whose site Maniacstore.com accounted for 10 percent of overall sales this year.

When e-commerce marketplaces launched in India they opened up a nationwide market that most small enterprises had not dreamt of until then. Indian SMEs are not insignificant. According to the Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises there are 36 million small units. These units have created employment for over 80 million Indians, contributed about eight percent to the GDP and accounted for 45 percent of the total manufacturing output and 40 percent of exports.

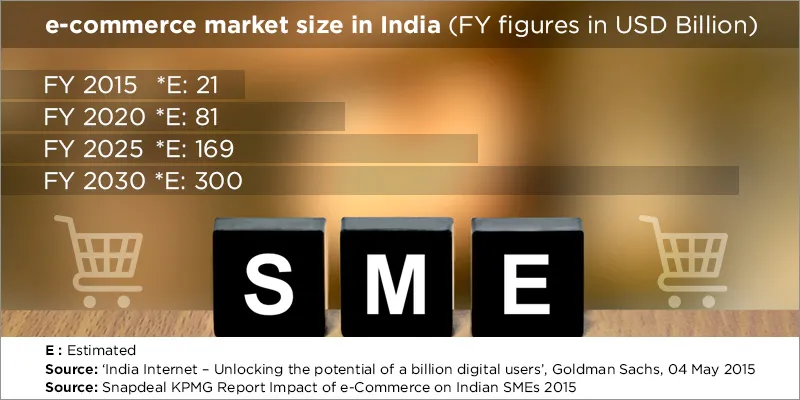

With the launch of e-commerce marketplaces, the hope was that these millions of small enterprises could participate in the ‘bounty of online commerce’. According to the recent ‘Snapdeal-KPMG Report Impact of e-Commerce on Indian SMEs 2015’ Indian e-commerce sector will be worth $80 billion by 2020, and $300 billion by 2030.

Many small sellers, like Suraj, have already benefited from this boom. Snapdeal alone has about 200,000 sellers on its platform. However, with these private limited companies not releasing sales contribution data, it is still unclear how many small enterprises have truly seen value like Suraj has. This is especially true when merchants indirectly promoted by the marketplaces, like WS Retail for Flipkart and Cloudtail for Amazon, reportedly contribute a chunk of their sales.

Yes, there are good times

A number of small retailers have seen sales zoom thanks to online retail. Online marketplaces like Flipkart, Amazon and Snapdeal provide SMEs with improved market reach at lower costs. Marketplaces, through their marketing, ensure customer ‘footfalls’ on the site, support sellers in terms of inventory to be held and logistics.

“There is no big money needed to start selling online. From day one, you start getting customers,” said Sayak Sahu, Co-founder of SmileDrive, an online seller of electronic gadgets.

This low-investment model has attracted a number of small offline retailers. Bangalore-based Magicworks, an importer and distributor of toys, started selling on Amazon and Flipkart two years ago. “It makes the system a level-playing field. Most of these players reach out to the sellers and they do the necessary handholding for you to be comfortable with the system,” said Nilesh, owner of Magicworks, who wanted to be identified only by his first name. For Magicworks, revenue has increased by 20 percent after joining online marketplaces in 2012. “Initially online sale was growing at 100 percent a year. In the last couple of years, it has grown 40-50 percent a year,” Nilesh told YourStory.

Many offline players have completely shifted to online. Delhi-based Lifelong, a home appliances brand, shutdown operations in 1999 due to issues with retailers. But the euphoria around online retail led Bharat Kalia, whose family runs other manufacturing businesses, to relaunch Lifelong this September as a seller on marketplaces.

For Lifelong, online sales have brought profit much better than the traditional offline channel could have, said Bharat. Since they save up to 40 percent in supply chain expenses, Lifelong is able to give products at a cheaper rate than their competitors. “We hit our target in a month after we launched; customer turnaround is fast in online platforms,” said Bharat, who is targeting Rs 1 crore in sales during the Diwali season.

Trouble with a capital T

However, it is not all hunky-dory. Many sellers still do not completely understand the functioning of marketplaces. Quite a few merchants complained that mainstream e-marketplaces seldom support small sellers. To counter this, sellers like Maniacstore are now planning to launch their own marketplaces. “Within two weeks, our website will be an entirely new marketplace for new sellers who are not as big as those on Snapdeal or Amazon. We will not be able to give discounts like they do; but we will sell products which are not discounted by them or are out of stock, with more details on technical specifications,” said Suraj. Besides, there will be a specific category for refurbished and open box products.

Returned goods, which could turn into refurbished or open box products, are a big concern for sellers. Often, merchants claim, customers replace the product, or use it, or open the package, and then return it. But the customers are reimbursed by marketplaces without checking the condition of the returned product. “Once a fresh order is placed, we have to once again send the same product immediately—without having time to check the product which we get back from the warehouse in about 20 days. The marketplaces take the commission the first time, but shipping charges twice,” said Sayak of Smiledrive.

Another common complaint among the merchants is that marketplaces change their commission structure quite often, affecting sellers’ profit. Inadequate financing is another factor, the Snapdeal-KPMG report said, as 41 percent of them have no access to bank loans.

B2B troubles

Despite the issues, for small retailers it is better to be online rather than only offline. However, for B2B players, who make up a majority of small enterprises, the problems are bigger. “E-marketplaces mostly sell end products; very few SMEs produce consumer products. They mostly manufacture products as per designs requested by customer—which do not go into e-commerce,” said V K Dikshit, president of Karnataka Small Scale Industries Association (KASSIA).

“In the long term, ecommerce is not significant for (B2B) SMEs. It does not give the minimum exposure required in the market to get customers,” said Bankim D Mistry, president of Bombay Small Scale Industries Association (BSSIA). Bankim is Director of Bharat Traders, a manufacturer of printing and film processing equipment. Most SMEs, who are focused on manufacturing, have not built a brand and so their products fall in the ‘other brands’ category on most marketplaces resulting in lower exposure. Most marketplaces also require products to have a bar-code, which many SME-manufactured goods do not have. “E-commerce is only for corporate brands, not industrial products. Whatever money spent on e-commerce over the last ten years has hence been a waste for SMEs. We would rather stick to traditional methods for marketing,” he said.

But the real issue is not the availability of platforms. Out of the six lakh MSMEs in Karnataka, hardly 50,000 have online presence. Low internet penetration has restricted e-commerce growth in rural and semi-urban areas, where many of the SMEs are present. “With only four hours of power available per day in tier-II cities, how can this industry thrive? Government should come in a big way to help small B2B players,” Dikshit said.