7 common myths about working with the Indian government

Ministry. Secretariat. Collectorate. Panchayat Samiti.

Sir. Madam. Sir. Madam.

Meeting. Field Visit. Presentation.

New Delhi. Nagpur. Noamundi.

These are the words around which my life revolves currently.

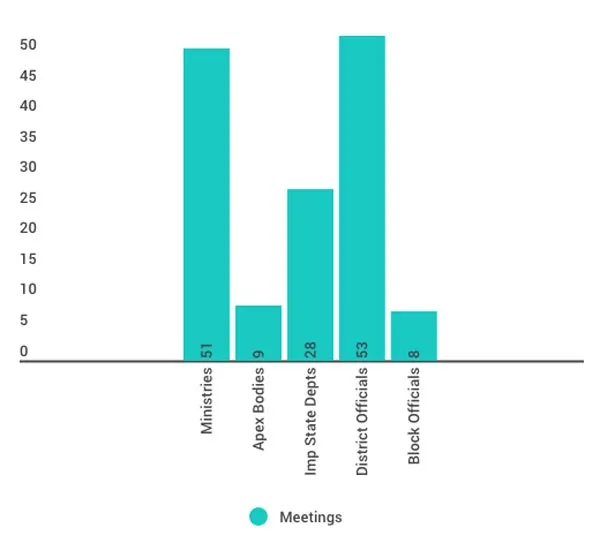

At SocialCops, we work on a large number of projects with the government. Typically, our data platform helps some of the most important decision-makers in the country get crucial insights. We have deployed our platform at multiple levels of the government — apex bodies, national ministries, state governments, and even district governments.

Our partnerships team has attended over 150 government meetings since January 2016. This includes meetings with officials at various levels and with varied agendas — introductory meetings, deployments, feedback sessions, and even policy discussions.

When I joined SocialCops a year ago, I had limited experience working with the government. However, within a year, I can proudly say that I have met ministers, spoken at press launches by MPs, visited villages in the remotest tribal belts, met with over 25 IAS officers, and even had some of these officers buy me coffee at Starbucks.

In India, many of us grow up thinking that the government lacks good intent and productivity. However, in the past year, I have had the opportunity to meet and work with a number of government officials, some of whom were among the most hard working, efficient, and driven people I have met.

Here are seven myths about the government that I learned were wrong.

Myth number 1: A government job is from 9 to 5

Most people believe that government officers have a cozy nine-to-five job. There couldn’t be a bigger myth about them. Most IAS officers start their day as early as at 8 am and sometimes work as late as 2 am.

Don’t believe me? Here is a list of the earliest and latest meetings that we have attended.

Earliest meeting start time: 9 am

- First meeting with the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare

- First meeting with the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare

- Update meeting with the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation

Latest meeting start time: 12:30 am

- Update meeting with a District Collector

- Update call with a central ministry official (12:45 am)

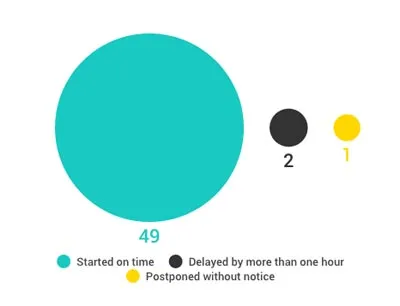

Myth number 2: Government meetings never start on time

This is a very common myth, though it is usually wrong. In fact, most officers have their staff call us one day in advance to get the details of the attendees and presentations. That helps most meetings start on time.

Here’s a graphic showing data on my 52 meetings so far.

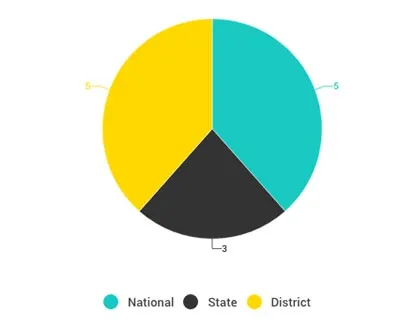

Myth number 3: The government does not work on the weekends

I have seen a number of my friends in the corporate world yearn for 6 pm on Fridays and their ever-so-sacred weekends. However, many officers and elected representatives in the government have scheduled meetings at 8 pm on Friday, 9 am on Saturday, and even 4 pm on Sunday. Here’s some data on these meetings.

Meetings on holidays: three

I have even accompanied an IAS officer on a field visit to interact with villagers on a weekend when the entire state was celebrating Rama Navami!

Meetings on weekends: 13

Here’s the breakup of these 13 meetings with government officials from the past six months.

Myth number 4: Government work is very slow

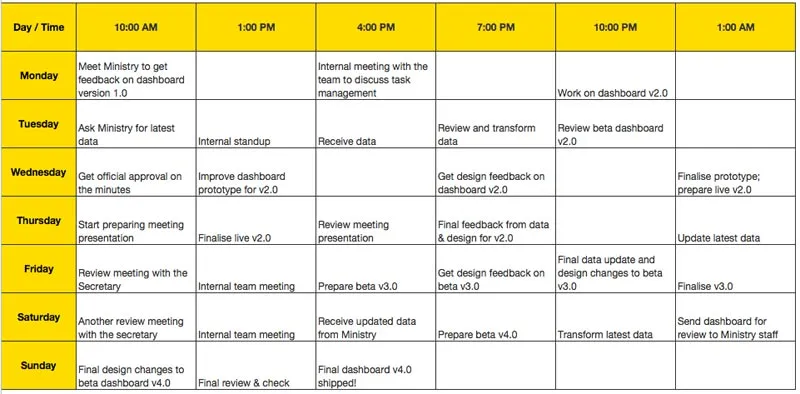

As is typical of startups, we are quite used to working crazy hours. To our surprise, we have received some of our craziest deadlines from government partners. It’s endearing to see the government working on startup timelines as well.

We were working with a national ministry to build a dashboard that tracks the outreach of a scheme. Here’s a week full of deadlines, requests, and responses for that project.

Sir, what is our next deadline?”

“Yesterday!”

That is how some of our negotiations on timelines start! I think of the government as a company, but with a billion clients and a complex hierarchy. At SocialCops, we work with over 150 organisations — corporates, government, philanthropic foundations, and non-profits — yet, among all our clients, the government is often the most demanding.

Myth number 5: It is mandatory to be grey-haired to voice your opinion

When I graduated from LSR, I was told that creating an impact in policy requires years of patience and hard work to finally reach a position where your opinion counts enough to drive real change.

However, at SocialCops, I was surprised to find that government officials ask our opinions on important issues.

For example, when my colleague was meeting with a senior official in a central ministry for the first time, the first thing he asked when she entered his office was, “What do you think is going wrong with our programme?” She then spoke about ways in which the data collection and dissemination processes could be improved. The official further asked her, “Tell me, as a normal citizen, what do you think about the scheme? Do you think an average Indian will understand the scheme? What can we do better?” It is indeed heartening to see government officers ask us for such multi-faceted feedback on their work.

Though the average age of our partnerships team is just 24, many government officials we have worked with have been very open to our ideas. They understand that in the upcoming era of digital governance, it doesn’t take 20 years to push for change.

Myth number 6: People at the grassroots are not knowledgeable

This is a myth that needs to be broken within the government itself first. I have sometimes heard senior officials complain about the capabilities of their junior staff. Yet I have been pleasantly surprised by some of the individuals I’ve met in the junior rungs of the government. Whenever I need to understand a data problem, I have always relied on the department computer operators, middle order clerks, and even assistants for a solution.

A few months ago, I was in Nagpur, trying to understand how to triangulate data across 32 portals for the health department. I spoke to every official — the District Health Officer, Additional District Health Officer, MIS in charge — to try to understand where every piece of health data resides. Everyone gave me the same remark: “Madam, why don’t you look at the portals first?” This wasn’t ideal, since this meant opening every one of the 32 portals and cross-checking what data is on each portal. Eventually, I found a recent postgraduate from a local college working as a computer operator, who gave me a full picture of the data system, told me exactly where data mismatches are likely, and how they can be cross-checked.

Many “junior” government staff members have used their field knowledge to help me with some of the most interesting data challenges: how to triangulate data, why village names in India won’t match, what data points are important to track on a regular basis, and how digitalisation can be fast-tracked. It’s not an exaggeration to say that some of their insights and solutions were more practical than what I have read in research papers or heard in podcasts.

Myth number 7: The government is not data-driven or does not believe in data

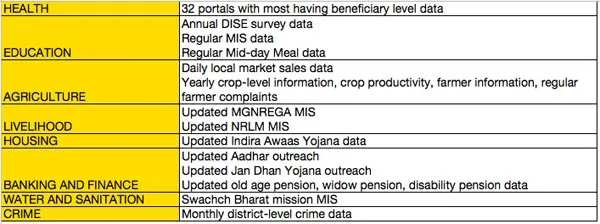

This is a myth that we at SocialCops too have had — the government doesn’t have the data and, when it does, it does not use it. However, we are glad to have been proven wrong. Here are examples of some of the most important data sets that the government maintains regularly.

The government does maintain important data. However, there are two key reasons why politicians and government officers are unable to use data to drive decisions — no time to analyse large data sets, and no time to access first-hand field information.

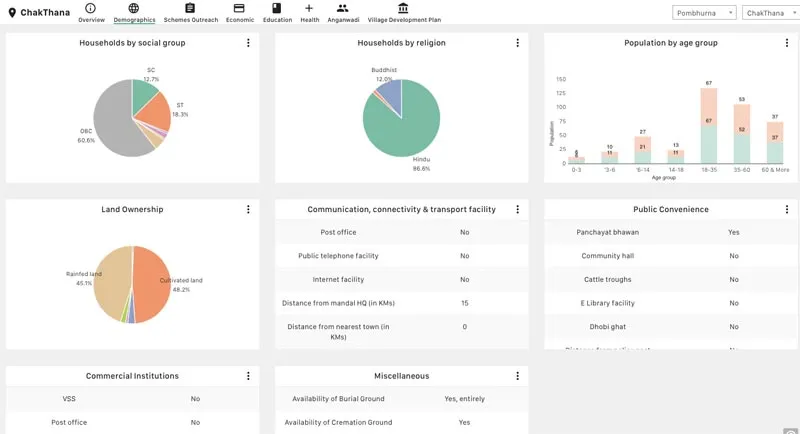

This is where data visualisation can help save a lot of time. Our insightful dashboards help drive better decisions by providing a high-level overview to decision-makers while giving them the flexibility to drill down to granular data.

For example, we built a village development dashboard for a district in Maharashtra, in partnership with Tata Trusts. On May 5, 2016, the Finance Minister of Maharashtra, who is also the Guardian Minister for this district, was reviewing a sub-district’s progress at a public conference. When the Public Health Engineering Department’s officer claimed that the reach of tap water connections was almost 100 percent, I quickly searched through our dashboard and reported that 8,700 of around 13,000 households did not have a tap water connection. The Finance Minister noted that this needed to be fixed. During the course of the meeting, I used the dashboard’s data to raise more issues to the Finance Minister. This is truly data-driven planning.

Working with the government is a roller coaster ride. One day I might be sitting in an old British building in Central Delhi with a Principal Secretary of a national scheme, while the next day I might be in a village in Jharkhand working with the block officer on a widow pension scheme. I don’t think any classroom across the world can teach me as much about governance and the development sector as these meetings have. For a 23-year-old with just a bachelors degree, that’s a lot of mastery.

Signing off for another Central Delhi expedition!

The article first appeared here.

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of YourStory.)