When does pure discounting make sense for B2C companies?

The Zones of Discovery and Trust

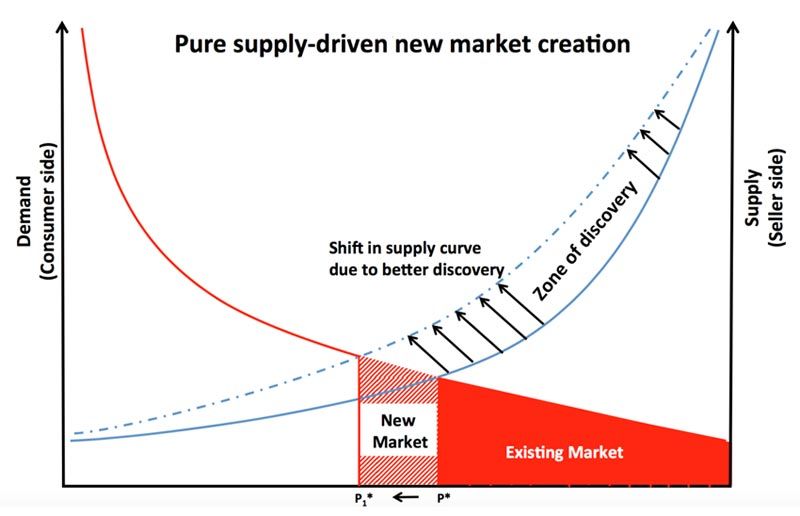

Back in my ground-digging days, there were two terms in use – resources and reserves. ‘Resources’ referred to all the mineral ore in the ground while ‘reserves’ were the subpart of resources that were extractable at a profit. Similarly, in economics, the area under the demand curve represents all the ‘resources’, but it is only at the price point P* and beyond that the supplier is deemed to be making a profit. It is at P* and beyond that the market exists. This concept has been around since time immemorial, or at least since grandad Adam Smith posited that

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.

Zone of discovery

The natural order of things prevailed until aggregators came along to wreak a bit of havoc on both sides. To focus first on the supply side, aggregators have been convincing suppliers that through better listing of their services/products on a single portal, better inventory utilisation occurs which can enable the supplier to reduce prices while making the same profit margins. Thus, according to this argument, the supplier is deemed to be making a profit at the lowered price P1*. The shift in the supply curve owing to this price reduction is what I term the “zone of discovery”. Customers “discover” new supply through the organised listing of services in much the same way as commerical yellow pages enabled the organised listing of business in the offline era. However, as the suppliers are yet to be convinced by the theory, the aggregator agrees to bear the subsidy cost of the price decrease to cater for the creation of a new market.

Note that this is based on a big hypothesis: Discovery leads to better inventory utilisation.

Source: http://www.imagineforest.com/blog/top-10-winnie-the-pooh-quotes-with-pictures/

The key point, here, as Winnie the Pooh rightly observes, is that the market needs to be disorganized to enable discovery. If services/products are already easily “findable”, the value proposition of discovery does not makes much sense. Unfortunately, tools such as Google and, particularly in India, Justdial have been reducing the disorder in the marketplace through better categorisation and listing of products and services. Thus, true discovery now occurs primarily for impulse purchases — where the need is urgent enough to prevent the multiple-browser-tab/app-open-price-compare situation (known as multi-homing) present in almost every other category for the Indian consumer.

Here, food makes it to the very top of the list. Other categories I can think of, off the top of my head, are plumbers (blocked toilet, leaky faucet situations) and doctors (emergency situations). Thus, companies such as Zomato, Practo and UrbanClap (the latter in certain kinds of professions) make the cut in terms of making discovery possible.

Even these firms face problems when other competitors come up. For instance, the emergence of Foodpanda and Swiggy made food ordering less of an impulse purchase and more of a price comparison. However, Zomato is trying to evolve in the eating-out, restaurant discovery and table reservation businesses to maintain its edge.

For the individual supplier, it is a straight toss up between the take-rate (commission) charged by the aggregator and the resulting improvement in inventory utilisation attributable to discovery. Thus, the new market created through price reduction is worthwhile for the aggregator if the long-term take rate target adequately reflects the value provided to the supplier in terms of utilisation. Here, a lot of aggregators have initially tried to get suppliers onboard with a low take rate, with plans to increase this down the road. However, if the economics of utilisation do not stack up for the supplier, he/she will opt out at the point where the raised take rate does not create enough value to justify remaining on the aggregator’s portal.

Zone of trust

Aggregators can also work to effect a change on the demand side in what I call the “zone of trust”. The classic switch-and-bait model, which is prevalent in certain markets, leads to a trust deficit on the consumer side, leading to reduced demand. If the platform can make an investment in technology to ensure better certification/branding, greater trust in the product/service eventuates and higher demand will follow. It is interesting to note that the new equilibrium price of P2* should fundamentally support new demand characteristics. The extremely price sensitive market (shaded as 1 above) may be lost to the aggregator initially but the creation of market 2 becomes feasible. Once demand is captured, more suppliers come onboard of their own accord to bring prices back to P*, making market 1 feasible for capture as well.

A consistent, reliable customer experience is imperative for startups in this market. Some markets where this problem is being addressed are budget hotel aggregators, used-car dealers and to some extent, e-commerce retailers. Companies in the US such as Carfax have mastered this model, Carfax becoming the “one source of truth” when it comes to vehicle condition at sale. In India, apart from the used-car market, maintaining a high-level of customer trust has been a challenge due to the pursuit of a discounting strategy. Rather than making an investment in branding/certification, discounting is done to capture demand, and the supply brought on to match this goes without the implementation of appropriate vetting mechanisms. While cash on delivery models evolved in India to counter the doubting sceptics, these have proven inadequate so far in eliminating switch-and-bait tactics used by certain suppliers (discrepancies between what is shown online and what is actually received) and the resulting loss of trust has been hard to overcome.

The key then is to decide what “zone” a startup operates in before choosing to embark on a discounting strategy to capture market share — after all, creation of the market is temporary, its sustainability is what matters.

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of YourStory.)

![[Funding alert] Health education platform Virohan raises $2.8M across Seed and Series A rounds](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/b87effd06a6611e9ad333f8a4777438f/Image3vzm-1598348478370.jpg)