All you wanted to know about valuations, but did not know who to ask

Iska valuation mere valuation se zyada kaise? Startup founders are often found asking this to whoever cares to listen.

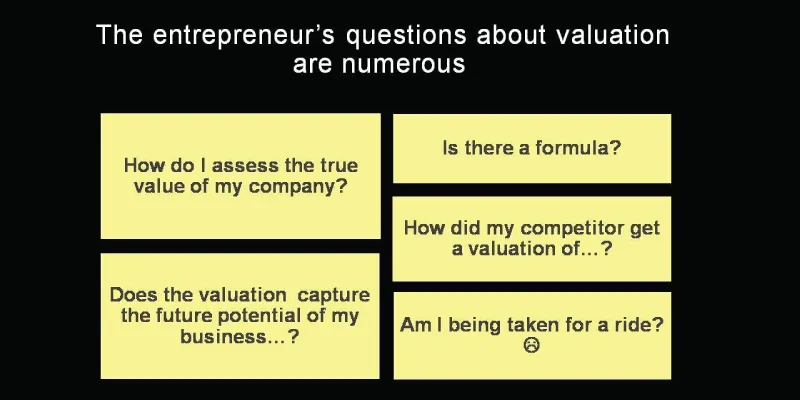

The topic of valuations causes a lot of heartburn when a startup finds itself in the market for funding. When you have slogged over your product or service for months, and the investor does not place the same value on it as you do, it can be frustrating.

In the course of her 26-year-long career, Bala Deshpande, Senior Managing Director, NEA India, has spent 16 years in the investment field, meeting more than 3,000 companies across sectors and stages. According to her, “One thing that is common to all entrepreneurs is that everyone turns around and asks, ‘so what is valuation?' ”

Speaking at the INKTalks conference recently, Bala threw some light on the thinking that goes behind valuations from the investor’s perspective. In her inimitable style and good humor, she showed the mirror not only to the entrepreneurs but to her tribe as well.

Valuations: art or science?

According to Bala, if she had to give a visual depiction of the process of valuation, she’d suppose it to be something like a Kalaripayattu performance. It is perhaps the right metaphor, as the word kalari was used to describe a battlefield or a combat arena in the ancient Sangam period.

So how do investors really value a company?

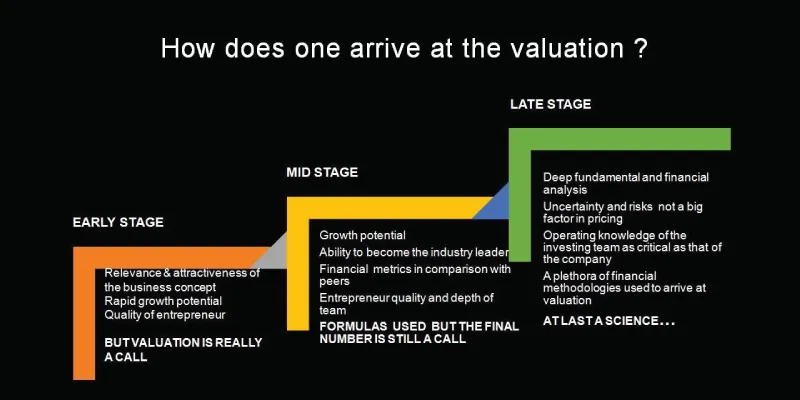

Bala explains it by taking the example of companies that are in different stages of their life cycle. “Let’s take GOQii, for example (NEA invested in it),” said Bala, adding, “What worked with them was that they were into the healthcare space which NEA is interested in. Plus, we knew Vishal (Gondal) as a serial entrepreneur. What we were backing were the entrepreneur and the concept.”

At an early stage, it is the promise that helps investors put a value on the table. “It is a call, there is no science behind it,” she said. It is essentially a sense of what the future will play out like.

Let’s take the next stage in a company’s lifecycle. At this stage, the company has been in existence for four or five years, has some revenue, but may not be profitable. “We had a fintech company approach us. We said 'fintech is a good sector, but will this company move from its existing model of providing services to providing digitised fintech?' And we felt the answer was 'yes',” she said.

According to Bala, “Again, we were clear that we are putting X million dollars in the company, valuing at Y million dollars, and we get X2 cost at an exit. So, at this stage, there’s some analysis of the numbers. But again, there is a call that this company will morph or change into something we think will be of great interest to investors to come five years down the line.” Thus, the call at this stage is taken for future investors’ interest in the company.

Large companies fall in the third stage. At this stage, they have executed and arrived at a certain level. Thus, the valuation process gets more scientific. “Let’s look at a pharma listed company. I would look at it and see how much money they are putting in R&D, how much of cash they are generating as a business, what is the current price earnings multiple, how much earnings arbitrage do I have, what is the discounted cash flows, and so on. It gets extremely technical,” she said.

Everything’s a marketplace

Essentially, the stage helps the investors decide how much is subjective and how much is objective. “But in all the cases, there is a strong subjective element in valuation. And that is where the confusion arises. 'Why did that fellow get that much valuation and why did I get this much', or very often 'why am I not getting a term sheet while she got one',” said Bala.

Half of the subjective element comes from the fact that during the meeting, the entrepreneur is giving cues to the investor whether they are capable of executing well, or are they capable of building a team, or for that matter, are they capable of taking the company to a logical level that they wanted to.

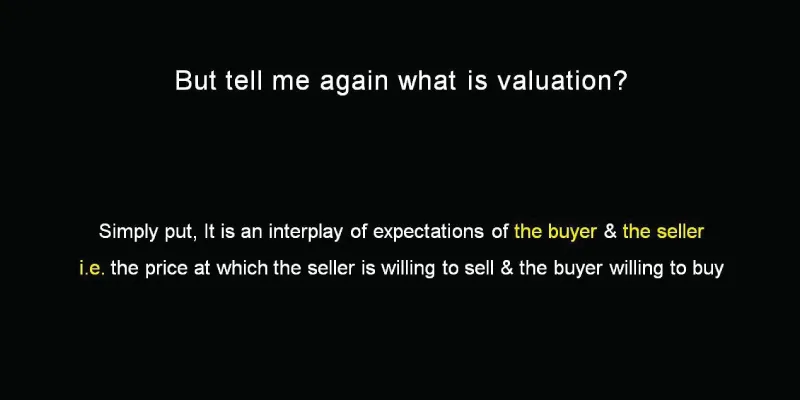

But what is valuation? As Bala put it, “It’s the price at which a seller (entrepreneur) is willing to sell and a buyer (investor) is willing to buy. It is a marketplace. As simple as that.”

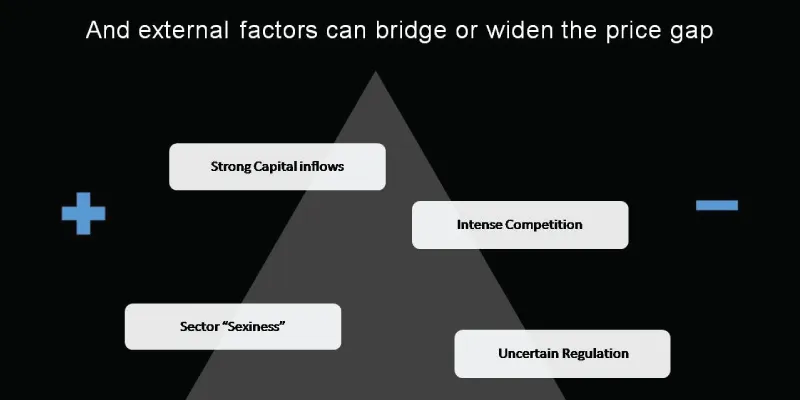

It, however, gets complicated because of the price gap that emerges, and that is where negotiations take the longest of time. Bala said, “The price gap comes essentially because you as an entrepreneur are looking at what you’ve built and created in the past. As an investor, I am looking at what I am buying for the future. The past perfect or the future perfect is the big differentiator here.”

The second point related to the price gap is that it is the entrepreneur who is betting on herself. “You know yourself 100 percent. But I am betting on you. There is one degree removed, and I will always discount for that,” she added.

JOMO rules now

It was interesting that Bala brought out the next point. In fact, it was even sporting of her to do so. “Now an investor wants high growth sectors to show in their portfolio. What confuses the whole issue is the different time frames and context to fundraising. There are times when investors chased you with term sheets, but the same VCs disappeared later. In our lingo, we have something called FOMO. That is the fear of missing out. There is also something called JOMO that is the joy of missing out, which is operating right now. ‘Yeaaah, I do not have an e-commerce in my portfolio.’ ”

She thus made her point that everyone is driven by the market. “We go by what we think is great investing sector right now, and there are some sectors we will avoid like a plague,” she said, as a matter of fact, adding that the bad news is that the process of valuations has got more complex.

Bala, though, ended on a positive note.

“I will just say this that as an entrepreneur, stick to building intrinsic value. Valuations is just a price that the market decides to pay or not. Stay on course and stay invested in your company. There’s a pot of gold at the end of it.”

Which domain name would you choose for your website? Click here to tell us.